The well-known log4j security vulnerability of December 2021 triggered a lot of renewed discussions around software supply chain security, and sometimes it has also been said to be an Open Source related issue.

This was not the first software component to have a serious security flaw, and it will not be the last.

What can we do about it?

This is the 10,000 dollar question that is really hard to answer. In this post I hope to help putting some light on to why it is such a hard problem. This comes from my view as an Open Source author and contributor since almost three decades now.

In this post I’m going to talk about security as in how we make our products have less bugs in the code we write and land on purpose. There is also a lot to be said about infrastructure problems such as consumers not verifying dependencies so that when malicious actors purposely destroy a component, users of that don’t notice the problem or supply chain security issues that risk letting bad actors insert malicious code into components. But those are not covered in this blog post!

The OSS Pyramid

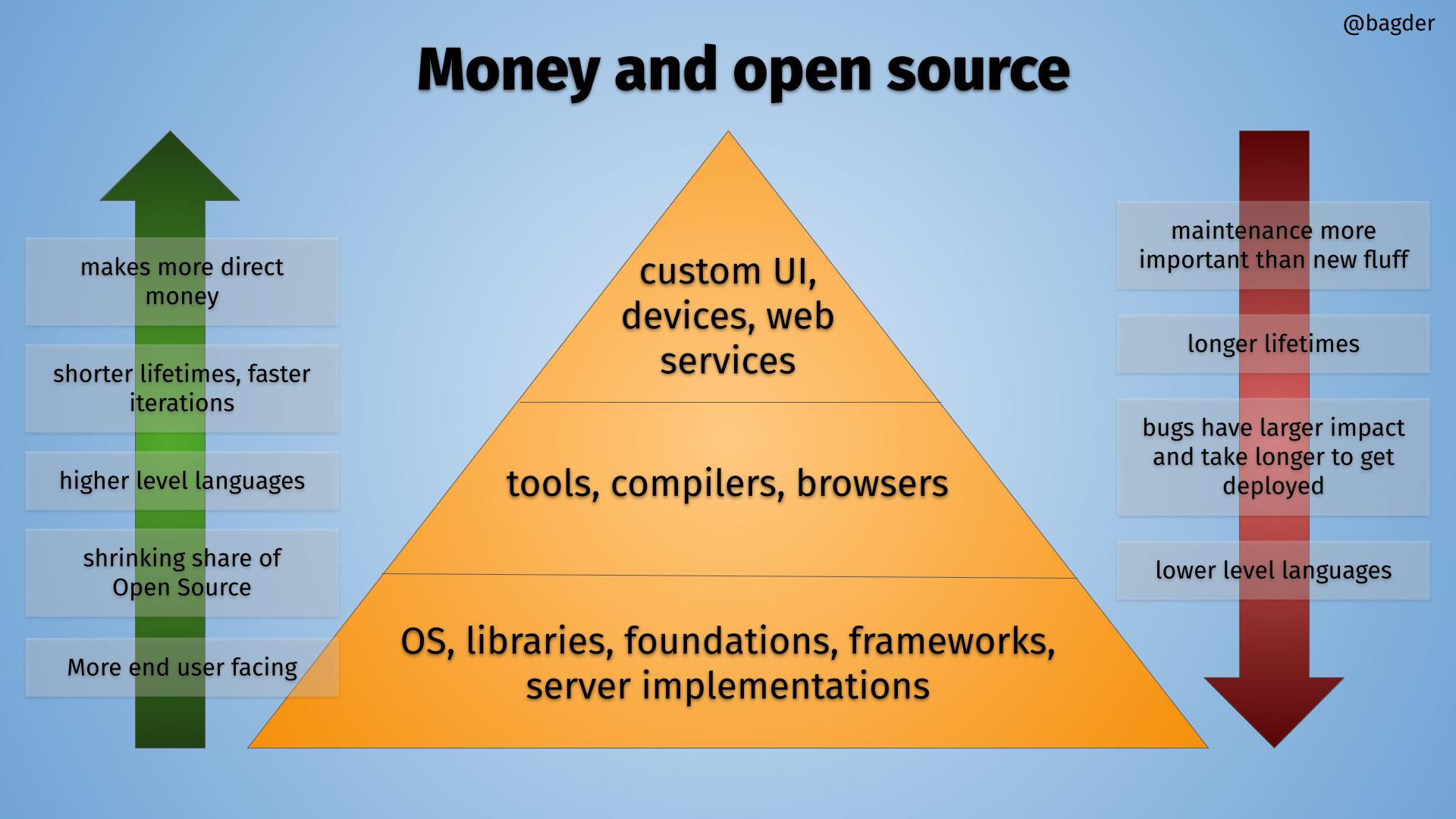

I think we can view the world of software and open source as a pyramid, and I made this drawing to illustrate.

Inside the pyramid there is a hierarchy where things using software are build on top of others, in layers. The higher up you go, the more you stand on the shoulders of open source components below you.

At the very bottom of the pyramid are the foundational components. Operating systems and libraries. The stuff virtually everything runs or depends upon. The components you really don’t want to have serious security vulnerabilities.

Going upwards

In the left green arrow, I describe the trend if you look at software when climbing upwards the pyramid.

- Makes more direct money

- Shorter lifetimes, faster iterations

- Higher level languages

- Shrinking share of Open Source

- More end user facing

At the top, there are a lot of things that are not Open Source. Proprietary shiny fronts with Open Source machines in the basement.

Going downwards

In the red arrow on the right, I describe the trend if you look at software when going downwards in the pyramid.

- Maintenance is more important than new fluff

- Longer lifetimes

- Bugs have larger impact and take longer to get deployed

- Lower level languages

At the bottom, almost everything is Open Source. Each component in the bottom has countless users depending on them.

It is in the bottom of the pyramid each serious bug has a risk of impacting the world in really vast and earth-shattering ways. That is where tightening things up may have the most positive outcomes. (Even if avoiding problems is mostly invisible unsexy work.)

Zoom out to see the greater picture

We can argue about specific details and placements within the pyramid, but I think largely people can agree with the greater picture.

Skyscrapers using free bricks

A little quote from my friend Stefan Eissing:

As a manufacturer of skyscrapers, we decided to use the free bricks made available and then maybe something bad happened with them. Where is the problem in this scenario?

Market economy drives “good enough”

As long as it is possible to earn a lot of money without paying much for the “communal foundation” you stand on, there is very little incentive to invest in or pay for maintenance of something – that also incidentally benefits your competitors. As long as you make (a lot of) money, it is fine if it is “good enough”.

Good enough software components will continue to have the occasional slip-ups (= horrible security flaws) and as long as those mistakes don’t truly hurt the moneymakers in this scenario, this world picture remains hard to change.

However, if those flaws would have a notable negative impact on the mountains of cash in the vaults, then something could change. It would of course require something extraordinary for that to happen.

What can bottom-dwellers do

Our job, as makers of bricks in the very bottom of the pyramid, is to remind the top brass of the importance of a solid foundation.

Our work is to convince a large enough share of software users higher up the stack that are relying on our functionality, that they are better off and can sleep better at night if they buy support and let us help them not fall into any hidden pitfalls going forward. Even if this also in fact indirectly helps their competitors who might rely on the very same components. Having support will at least put them in a better position than the ones who don’t have it, if something bad happens. Perhaps even make them avoid badness completely. Paying for maintenance of your dependencies help reduce the risk for future alarm calls far too early on a weekend morning.

This convincing part is often much easier said than done. It is only human to not anticipate the problem ahead of time and rather react after the fact when the problem already occurred. “We have used this free product for years without problems, why would we pay for it now?”

Software projects with sufficient funding to have engineer time spent on the code should be able to at least make serious software glitches rare. Remember that even the world’s most valuable company managed to ship the most ridiculous security flaw. Security is hard.

(How we work to make sure curl is safe.)

Components in higher levels can help

All producers of code should make sure dependencies of theirs are of high quality. High quality here, does not only mean that the code as of right now is working, but they should also make sure that the dependencies are run in ways that are likely to continue to produce good output.

This may require that you help out. Add resources. Provide funding. Run infrastructure. Whatever those projects may need to improve – if anything.

The smallest are better off with helping hands

I participate in a few small open source projects outside of curl. Small projects that produce libraries that are used widely. Not as widely as curl perhaps, but still millions and millions of users. Pyramid-bottom projects providing infrastructure for free for the moneymakers in the top. (I’m not naming them here because it doesn’t matter exactly which ones it is. As a reader I’m sure you know of several of this kind of projects.)

This kind of projects don’t have anyone working on the project full-time and everyone participates out of personal interest. All-volunteer projects.

Imagine that a company decides they want to help avoiding “the next log4j flaw” in such a project. How would that be done?

In the slightly larger projects there might be a company involved to pay for support or an individual working on the project that you can hire or contract to do work. (In this aspect, curl would for example count as a “slightly larger” kind.)

In these volunteers-only projects, all the main contributors work somewhere (else) and there is no established project related entity to throw money at to fix issues. In these projects, it is not necessarily easy for a contributor to take on a side project for a month or two – because they are employed to do something else during the days. Day-jobs have a habit of taking a few weeks or months off for a side project difficult.

Helping hands would, eh… help

Even the smallest projects tend to appreciate a good bug-fix and getting things from the TODO list worked on and landed. It also doesn’t add too much work load or requirements on the volunteers involved and it doesn’t introduce any money-problems (who would receive it, taxation, reporting, etc).

For projects without any existing way setup or available to pay for support or contract work, providing man power is for sure a good alternative to help out. In many cases the very best way.

This of course then also moves the this is difficult part to the company that wants the improvement done (the user of it), as then they need to find that engineer with the correct skills and pay them for the allotted time for the job etc.

The entity providing such helping hands to smaller projects could of course also be an organization or something dedicated for this, that is sponsored/funded by several companies.

A general caution though: this creates the weird situation where the people running and maintaining the projects are still unpaid volunteers but people who show up contributing are getting paid to do it. It causes unbalances and might be cause for friction. Be aware. This needs to be done in close cooperating with the maintainers and existing contributors in these projects.

Not the mythical man month

Someone might object and ask what about this notion that adding manpower to a late software project makes it later? Sure, that’s often entirely correct for a project that already is staffed properly and has manpower to do its job. It is not valid for understaffed projects that most of all lack manpower.

Grants are hard for small projects

Doing grants is a popular (and easy from the giver’s perspective) way for some companies and organizations who want to help out. But for these all-volunteer projects, applying for grants and doing occasional short-term jobs is onerous and complicated. Again, the contributors work full-time somewhere, and landing and working short term on a project for a grant is then a very complicated thing to mix into your life. (And many employers actively would forbid employees to do it.)

Should you be able to take time off your job, applying for grants is hard and time consuming work and you might not even get the grant. Estimating time and amount of work to complete the job is super hard. How much do you apply for and how long will it take?

Some grant-givers even assume that you also will contribute so to speak, so the amount of money paid by the grant will not even cover your full-time wage. You are then, in effect, expected to improve the project by paying parts of the job yourself. I’m not saying this is always bad. If you are young, a student or early in your career that might still be perfect. If you are a family provider with a big mortgage, maybe less so.

In Nebraska since 2003

A more chaotic, more illustrative and probably more realistic way to show “the pyramid”, was done by Randall Munroe in his famous xkcd 2347 image, which, when applied onto my image looks like this:

Generalizing

Of course lots of projects in the bottom make money and are sufficiently staffed and conversely not all projects in the top are proprietary money printing business. This is a simplified image showing trends and the big picture. There will always be exceptions.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh