2022-3-31 23:4:0 Author: www.sentinelone.com(查看原文) 阅读量:39 收藏

By Juan Andres Guerrero-Saade(@juanandres_gs) and Max van Amerongen (@maxpl0it)

Executive Summary

- On Thursday, February 24th, 2022, a cyber attack rendered Viasat KA-SAT modems inoperable in Ukraine.

- Spillover from this attack rendered 5,800 Enercon wind turbines in Germany unable to communicate for remote monitoring or control.

- Viasat’s statement on Wednesday, March 30th, 2022 provides a somewhat plausible but incomplete description of the attack.

- SentinelLabs researchers discovered new malware that we named ‘AcidRain’.

- AcidRain is an ELF MIPS malware designed to wipe modems and routers.

- We assess with medium-confidence that there are developmental similarities between AcidRain and a VPNFilter stage 3 destructive plugin. In 2018, the FBI and Department of Justice attributed the VPNFilter campaign to the Russian government

- AcidRain is the 7th wiper malware associated with the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Context

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has included a wealth of cyber operations that have tested our collective assumptions about the role that cyber plays in modern warfare. Some commentators have voiced a bizarre disappointment at the ‘lack of cyber’ while those at the coalface are overwhelmed by the abundance of cyber operations accompanying conventional warfare. From the beginning of 2022, we have dealt with six different strains of wiper malware targeting Ukraine: WhisperKill, WhisperGate, HermeticWiper, IsaacWiper, CaddyWiper, and DoubleZero. These attacks are notable on their own. But there’s been an elephant in the room by way of the rumored ‘satellite modem hack’. This particular attack goes beyond Ukraine.

We first became aware of an issue with Viasat KA-SAT routers due to a reported outage of 5,800 Enercon wind turbines in Germany. To clarify, the wind turbines themselves were not rendered inoperable but “remote monitoring and control of the wind turbines” became unavailable due to issues with satellite communications. The timing coincided with the Russian invasion of Ukraine and suspicions arose that an attempt to take out Ukrainian military command-and-control capabilities by hindering satellite connectivity spilled over to affect German critical infrastructure. No technical details became available; technical speculation has been rampant.

On Wednesday, March 30th, 2022, Viasat finally released a statement stating that the attack took place in two phases: First, a denial of service attack coming from “several SurfBeam2 and SurfBeam2+ modems and […other on-prem equipment…] physically located within Ukraine” that temporarily knocked KA-SAT modems offline. Then, the gradual disappearance of modems from the Viasat service. The actual service provider is in the midst of a complex arrangement where Eutalsat provides the service, but it’s administered by an Italian company called Skylogic as part of a transition plan.

The Viasat Explanation

At the time of writing, Viasat has not provided any technical indicators nor an incident response report. They did provide a general sense of the attack chain with conclusions that are difficult to reconcile.

Viasat reports that the attackers exploited a misconfigured VPN appliance, gained access to the trust management segment of the KA-SAT network, moved laterally, then used their access to “execute legitimate, targeted management commands on a large number of residential modems simultaneously”. Viasat goes on to add that “these destructive commands overwrote key data in flash memory on the modems, rendering the modems unable to access the network, but not permanently unusable”.

It remains unclear how legitimate commands could have such a disruptive effect on the modems. Scalable disruption is more plausibly achieved by pushing an update, script, or executable. It’s also hard to envision how legitimate commands would enable either the DoS effects or render the devices unusable but not permanently bricked.

In effect, the preliminary Viasat incident report posits the following requirements:

- Could be pushed via the KA-SAT management segment onto modems en masse

- Would overwrite key data in the modem’s flash memory

- Render the devices unusable, in need of a factory reset or replacement but not permanently unusable.

With those requirements in mind, we postulate an alternative hypothesis: The threat actor used the KA-SAT management mechanism in a supply-chain attack to push a wiper designed for modems and routers. A wiper for this kind of device would overwrite key data in the modem’s flash memory, rendering it inoperable and in need of reflashing or replacing.

The AcidRain Wiper

On Tuesday, March 15th, 2022, a suspicious upload caught our attention. A MIPS ELF binary was uploaded to VirusTotal from Italy with the name ‘ukrop’. We didn’t know how to parse the name accurately. Possible interpretations include a shorthand for “ukr”aine “op”eration, the acronym for the Ukrainian Association of Patriots, or a Russian ethnic slur for Ukranians – ‘Укроп’. Only the incident responders in the Viasat case could say definitively whether this was in fact the malware used in this particular incident. We posit its use as a fitting hypothesis and will describe its functionality, quirky development traits, and possible overlaps with previous Russian operations in need of further research.

Technical Overview

| SHA256 | 9b4dfaca873961174ba935fddaf696145afe7bbf5734509f95feb54f3584fd9a |

| SHA1 | 86906b140b019fdedaaba73948d0c8f96a6b1b42 |

| MD5 | ecbe1b1e30a1f4bffaf1d374014c877f |

| Name | ukrop |

| Magic | ELF 32-bit MSB executable, MIPS, MIPS-I version 1 (SYSV), statically linked, stripped |

| First Seen | 2022-03-15 15:08:02 UTC |

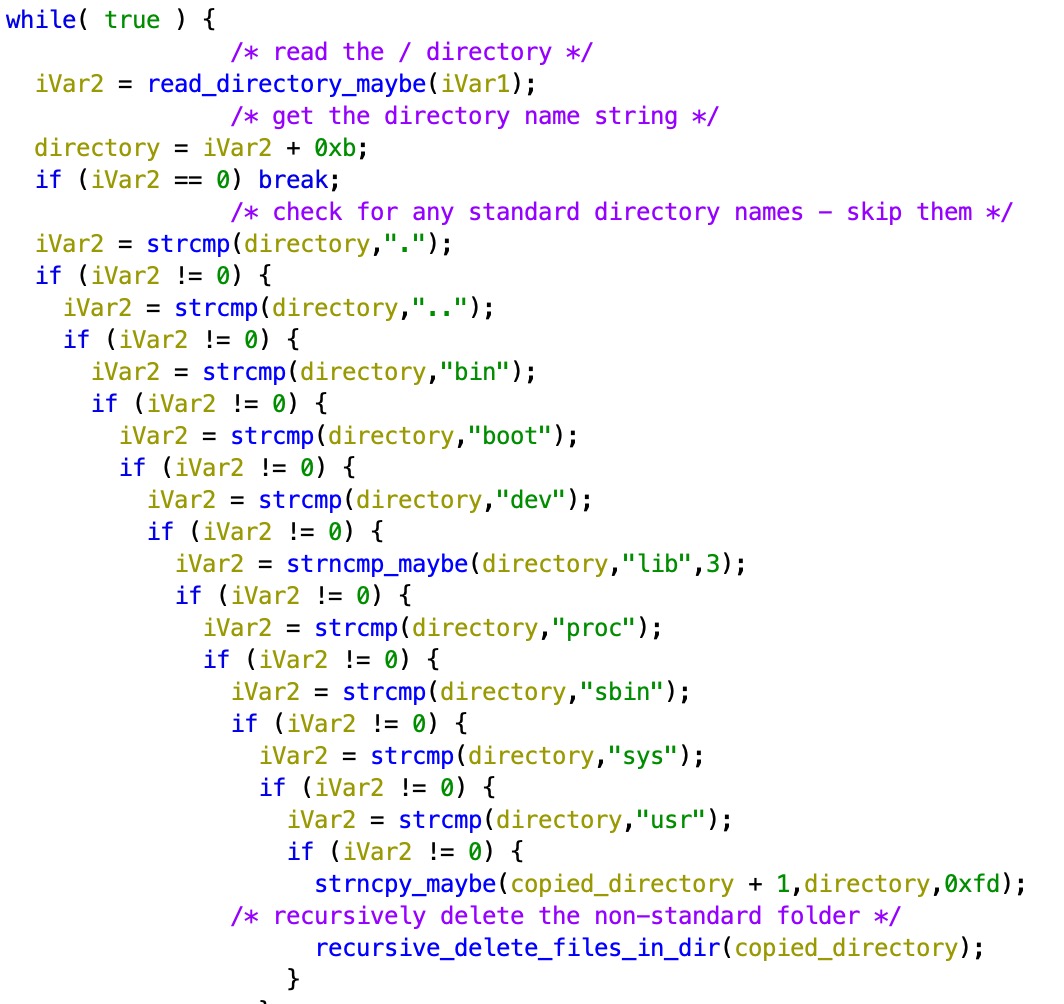

AcidRain’s functionality is relatively straightforward and takes a bruteforce attempt that possibly signifies that the attackers were either unfamiliar with the particulars of the target firmware or wanted the tool to remain generic and reusable. The binary performs an in-depth wipe of the filesystem and various known storage device files. If the code is running as root, AcidRain performs an initial recursive overwrite and delete of non-standard files in the filesystem.

Following this, it attempts to destroy the data in the following storage device files:

| Targeted Device(s) | Description |

| /dev/sd* | A generic block device |

| /dev/mtdblock* | Flash memory (common in routers and IoT devices) |

| /dev/block/mtdblock* | Another potential way of accessing flash memory |

| /dev/mtd* | The device file for flash memory that supports fileops |

| /dev/mmcblk* | For SD/MMC cards |

| /dev/block/mmcblk* | Another potential way of accessing SD/MMC cards |

| /dev/loop* | Virtual block devices |

This wiper iterates over all possible device file identifiers (e.g., mtdblock0 – mtdblock99), opens the device file, and either overwrites it with up to 0x40000 bytes of data or (in the case of the /dev/mtd* device file) uses the following IOCTLS to erase it: MEMGETINFO, MEMUNLOCK, MEMERASE, and MEMWRITEOOB. In order to make sure that these writes have been committed, the developers run an fsync syscall.

When the overwriting method is used instead of the IOCTLs, it copies from a memory region initialized as an array of 4-byte integers starting at 0xffffffff and decrementing at each index. This matches what others had seen after the exploit had taken place.

The code for both erasure methods can be seen below:

Once the various wiping processes are complete, the device is rebooted.

This results in the device being rendered inoperable.

An Interesting Oddity

Despite what the Ukraine invasion has taught us, wiper malware is relatively rare. More so wiper malware aimed at routers, modems, or IoT devices. The most notable case is VPNFilter, a modular malware aimed at SOHO routers and QNAP storage devices, discovered by Talos. This was followed by an FBI indictment attributing the operation to Russia (APT28, in particular). More recently, the NSA and CISA attributed VPNFilter to Sandworm (a different threat actor attributed to the same organization, the Russian GRU) as the U.K.’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) described VPNFilter’s successor, Cyclops Blink.

VPNFilter included an impressive array of functionality in the form of multi-stage plugins selectively deployed to the infected devices. The functionality ranges from credential theft to monitoring Modbus SCADA protocols. Among its many plugins, it also included functionality to wipe and brick devices as well as DDoS a target.

The reason we bring up the specter of VPNFilter is not because of its superficial similarities to AcidRain but rather because of an interesting (but inconclusive) code overlap between a specific VPNFilter plugin and AcidRain.

VPNFilter Stage 3 Plugin – ‘dstr’

| SHA256 | 47f521bd6be19f823bfd3a72d851d6f3440a6c4cc3d940190bdc9b6dd53a83d6 |

| SHA1 | 261d012caa96d3e3b059a98388f743fb8d39fbd5 |

| MD5 | 20ea405d79b4de1b90de54a442952a45 |

| Description | VPNFilter Stage 3, ‘dstr’ module |

| Magic | ELF 32-bit MSB executable, MIPS, MIPS-I version 1 (SYSV), statically linked, stripped |

| First Seen | 2018-06-06 13:02:56 UTC |

After the initial discovery of VPNFilter, additional plugins were revealed by researchers attempting to understand the massive spread of the botnet and its many intricacies. Among these were previously unknown plugins, including ‘dstr’. As the mangled name suggests, it’s a ‘destruction’ module meant to supplement stage 2 plugins that lacked the ‘kill’ command meant to wipe the devices.

This plugin was brought to our attention initially by tlsh fuzzy hashing, a more recent matching library that’s proven far more effective than ssdeep or imphash in identifying similar samples. The similarity was at 55% to AcidRain with no other samples being flagged in the VT corpus. This alone is not nearly enough to conclusively judge the two samples as tied, but it did warrant further investigation.

VPNFilter and AcidRain are both notably similar and dissimilar. They’re both MIPS ELF binaries and the bulk of their shared code appears to stem from statically-linked libc. It appears that they may also share a compiler, most clearly evidenced by the identical Section Headers Strings Tables.

And there are other development quirks, such as the storing of the previous syscall number to a global location before a new syscall. At this time, we can’t judge whether this is a shared compiler optimization or a strange developer quirk.

More notably, while VPNFilter and AcidRain work in very different ways, both binaries make use of the MEMGETINFO, MEMUNLOCK, and MEMERASE IOCTLS to erase mtd device files.

There are also notable differences between VPNFilter’s ‘dstr’ plugin and AcidRain. The latter appears to be a far sloppier product that doesn’t consistently rise to the coding standards of the former. For example, note the redundant use of process forking and needless repetition of operations.

They also appear to serve different purposes, with the VPNFilter plugin targeting specific devices with hardcoded paths, and AcidRain taking more of a “one-binary-fits-all” approach to wiping devices. By brute forcing device filenames, the attackers can more readily reuse AcidRain against more diverse targets.

We invite the research community to stress test this developmental overlap and contribute their own findings.

Conclusions

As we consider what’s possibly the most important cyber attack in the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, there are many open questions. Despite Viasat’s statement claiming that there was no supply-chain attack or use of malicious code on the affected routers, we posit the more plausible hypothesis that the attackers deployed AcidRain (and perhaps other binaries and scripts) to these devices in order to conduct their operation.

While we cannot definitively tie AcidRain to VPNFilter (or the larger Sandworm threat cluster), we note a medium-confidence assessment of non-trivial developmental similarities between their components and hope the research community will continue to contribute their findings in the spirit of collaboration that has permeated the threat intelligence industry over the past month.

References

https://www.wired.com/story/viasat-internet-hack-ukraine-russia/

https://www.cisa.gov/uscert/ncas/alerts/aa22-076a

https://media.defense.gov/2022/Jan/25/2002927101/-1/-1/0/CSA_PROTECTING_VSAT_COMMUNICATIONS_01252022.PDF

https://www.airforcemag.com/hackers-attacked-satellite-terminals-through-management-network-viasat-officials-say/

https://nps.edu/documents/104517539/104522593/RELIEF12-4_QLR.pdf/9cc03d09-9af4-410e-b601-a8bffdae0c30

https://www.reuters.com/business/media-telecom/exclusive-hackers-who-crippled-viasat-modems-ukraine-are-still-active-company-2022-03-30/

https://www.viasat.com/about/newsroom/blog/ka-sat-network-cyber-attack-overview/

https://blog.talosintelligence.com/2018/05/VPNFilter.html

https://blog.talosintelligence.com/2018/06/vpnfilter-update.html?m=1

https://blog.talosintelligence.com/2018/09/vpnfilter-part-3.html

https://www.ncsc.gov.uk/files/Cyclops-Blink-Malware-Analysis-Report.pdf

https://www.trendmicro.com/en_us/research/21/a/vpnfilter-two-years-later-routers-still-compromised-.html

https://www.cisa.gov/uscert/ncas/alerts/aa22-054a

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh