Ransomware keeps making headlines. In a quest for profits, attackers target all types of organizations, from healthcare and educational institutions to service providers and industrial enterprises, affecting almost every aspect of our lives. In 2022, Kaspersky solutions detected over 74.2M attempted ransomware attacks which was 20% more than in 2021 (61.7M). Although early 2023 saw a slight decline in the number of ransomware attacks, they were more sophisticated and better targeted.

On the eve of the global Anti-Ransomware Day, Kaspersky looks back on the events that shaped the ransomware landscape in 2022, reviews the trends that were predicted last year, discusses emerging trends, and makes a forecast for the immediate future.

Looking back on last year’s report

Last year, we discussed three trends in detail:

- Threat actors trying to develop cross-platform ransomware to be as adaptive as possible

- The ransomware ecosystem evolving and becoming even more “industrialized”

- Ransomware gangs taking sides in the geopolitical conflict

These trends have persisted. A few months after last year’s blog post came out, we stumbled across a new multi-platform ransomware family, which targeted both Linux and Windows. We named it RedAlert/N13V. The ransomware, which focused on non-Windows platforms, supported the halting of VMs in an ESXi environment, clearly indicating what the attackers were after.

Another ransomware family, LockBit, has apparently gone even further. Security researchers discovered an archive that contained test builds of the malware for a number of less common platforms, including macOS and FreeBSD, as well as for various non-standard processor architectures, such as MIPS and SPARC.

As for the second trend, we saw that BlackCat adjusted their TTPs midway through the year. They registered domains under names that looked like those of breached organizations, setting up Have I Been Pwned-like websites. Employees of the victim organizations could use these sites to check if their names had popped up in stolen data, thus increasing the pressure on the affected organization to pay the ransom.

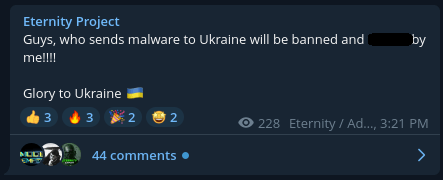

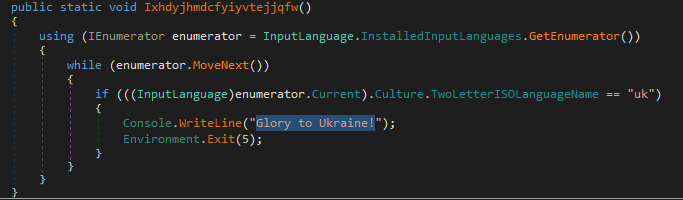

Although the third trend we spotted last year was one of ransomware gangs taking sides in the geopolitical conflict, it does not apply to them exclusively. There was one peculiar sample: a stealer called Eternity. We created a private report about this after an article claimed that the malware was used in the geopolitical conflict. Our research showed that there was a whole malware ecosystem around Eternity, including a ransomware variant. After the article appeared, the author made sure that the malware did not affect users in Ukraine and included a pro-Ukrainian message inside the malware.

The developer warns against using their malware in Ukraine

Pro-Ukrainian message inside the malware code

What else shaped the ransomware landscape in 2022

Ransomware groups come and go, and it is little wonder that some of them ceased operations last year as others emerged.

For example, we reported on the emergence of RedAlert/N13V, Luna, Sugar, Monster, and others. However, the most active family that saw light in 2022 was BlackBasta. When we published our initial report on BlackBasta in April 2022, we were only aware of one victim, but the number has since sharply increased. Meanwhile, the malware itself evolved, adding an LDAP-based self-spreading mechanism. Later, we encountered a version of BlackBasta that targeted ESXi environments, and the most recent version that we found supported the x64 architecture.

As mentioned above, while all those new groups entered the game, some others, such as REvil and Conti, went dark. Conti was the most notorious of these and enjoyed the most attention since their archives were leaked online and analyzed by many security researchers.

Finally, other groups like Clop ramped up their activities over the course of last year, reaching their peak in early 2023 as they claimed to have hacked 130 organizations using a single zero-day vulnerability.

Interestingly, the top five most impactful and prolific ransomware groups (according to the number of victims listed on their data leak sites) have drastically changed over the last year. The now-defunct REvil and Conti, which were second and third, respectively, in terms of attacks in H1 2022, gave way to Vice Society and BlackCat in Q1 2023. The remaining ransomware groups that formed the top five in Q1 2023, were Clop and Royal.

Top five ransomware groups by the number of published victims

| H1 2022 | H2 2022 | Q1 2023 | |||

| LockBit | 384 | LockBit | 368 | LockBit | 272 |

| REvil | 253 | BlackBasta | 176 | Vice Society | 164 |

| Conti | 173 | BlackCat | 113 | BlackCat | 85 |

| BlackCat | 100 | Royal | 74 | Clop | 84 |

| Vice Society | 54 | BianLian | 72 | Royal | 65 |

| Other | 384 | Other | 539 | Other | 212 |

Ransomware from an incident response perspective

Global Emergency Response Team (GERT) worked on many ransomware incidents last year. In fact, this was the number-one challenge they faced, although the share of ransomware in 2022 decreased slightly from 2021, going from 51.9% to 39.8%.

In terms of initial access, nearly half of the cases GERT investigated (42.9%) involved exploitation of vulnerabilities in public-facing devices and apps, such as unpatched routers, vulnerable versions of the Log4j logging utility, and so on. The second-largest category of cases consisted of compromised accounts and malicious emails.

The most popular tools employed by ransomware groups remain unchanged from year to year. Attackers have used PowerShell to collect data, Mimikatz to escalate privileges, PsExec to execute commands remotely, or frameworks like Cobalt Strike for all attack stages.

Our predictions for 2023 trends

As we looked back on the events of 2022 and early 2023, and analyzed the various ransomware families, we tried to figure out what the next big thing in this field might be. These observations produced three potential trends that we believe will shape the threat landscape for the rest of 2023.

Trend 1: More embedded functionality

We saw several ransomware groups extend the functionality of their malware during 2022. Self-spreading, real or fake, was the most noteworthy new addition. As mentioned above, BlackBasta started spreading itself by using the LDAP library to get a list of available machines on the network.

LockBit added a so-called “self-spreading” feature in 2022, saving its operators the effort needed to run tools like PsExec manually. At least, that is what “self-spreading” would normally suggest. In practice, this turned out to be nothing more than a credential-dumping feature, removed in later versions.

The Play ransomware, for one, does have a self-spreading mechanism. It collects different IPs that have SMB enabled, establishes a connection to these, mounts the SMB resources, then copies itself and runs on the target machines.

Self-propagation has been adopted by many notorious ransomware groups lately, which suggests that the trend will continue.

Trend 2: Driver abuse

Abusing a vulnerable driver for malicious purposes may be an old trick in the book, but it still works well, especially on antivirus (AV) drivers. The Avast Anti Rootkit kernel driver contained certain vulnerabilities that were previously exploited by AvosLocker. In May 2022, SentinelLabs described in detail two new vulnerabilities (CVE-2022-26522 and CVE-2022-26523) in the driver. These were later exploited by the AvosLocker and Cuba ransomware families.

AV drivers are not the only ones to be abused by malicious actors. Our colleagues at TrendMicro reported on a ransomware actor abusing the Genshin Impact anti-cheat driver by using it to kill endpoint protection on the target machine.

The trend of driver abuse continues to evolve. The latest case reported by Kaspersky is rather odd as it does not fit either of the previous two categories. Legitimate code-signing certificates, such as Nvidia’s leaked certificate and Kuwait Telecommunication Company’s certificate were used to sign a malicious driver which was then used in wiper attacks against Albanian organizations. The wiper used the rawdisk driver to get direct access to the hard drive.

We continue to follow ransomware gangs to see what new ways of abusing drivers they come up with, and we will be sharing our findings both publicly and on our TIP page.

Trend 3: Code adoption from other families to attract even more affiliates

Major ransomware gangs are borrowing capabilities from either leaked code or code purchased from other cybercriminals, which may improve the functionality of their own malware.

We recently saw the LockBit group adopt at least 25% of the leaked Conti code and issue a new version based entirely on that. Initiatives like these enable affiliates to work with familiar code, while the malware operators get an opportunity to boost their offensive capabilities.

Collaboration among ransomware gangs has also resulted in more advanced attacks. Groups are working together to develop cutting-edge strategies for circumventing security measures and improving their attacks.

The trend has given rise to ransomware businesses that build high-quality hack tools and sell them to other ransomware businesses on the black market.

Conclusion

Ransomware has been around for many years, evolving into a cybercriminal industry of sorts. Threat actors have experimented with new attack tactics and procedures, and their most effective approaches live on, while failed experiments have been forgotten. Ransomware can now be considered a mature industry, and we expect no groundbreaking discoveries or game-changers any time soon.

Ransomware groups will continue maximizing the attack surface by supporting more platforms. While attacks on ESXi and Linux servers are now commonplace, top ransomware groups are striving to target more platforms that might contain mission-critical data. A good illustration of this trend is the recent discovery of an archive with test builds of LockBit ransomware for macOS, FreeBSD, and unconventional CPU architectures, such as MIPS, SPARC, and so on.

In addition to that, TTPs that attackers use in their operations will continue to evolve — the driver abuse technique, which we discussed above, is a good example of this. To effectively counter ransomware actors’ ever-changing tactics, we recommend that organizations and security specialists:

- Update their software in a timely manner to prevent infection through vulnerability exploitation, one of the initial infection vectors most frequently used by ransomware actors.

- Use security solutions that are tailored protecting their infrastructure from various threats, including anti-ransomware tools, targeted attack protection, EDR, and so on.

- Keep their SOC or information security teams’ knowledge about ransomware tactics and techniques up to date by using the Threat Intelligence service, a comprehensive source of crucial information about new tricks that cybercriminals come up with.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh