2023-8-11 06:15:8 Author: unit42.paloaltonetworks.com(查看原文) 阅读量:70 收藏

Executive Summary

While the SugarCRM CVE-2023-22952 zero-day authentication bypass and remote code execution vulnerability might seem like a typical exploit, there’s actually more for defenders to be aware of. Because it’s a web application, if it’s not configured or secured correctly, the infrastructure behind the scenes can allow attackers to increase their impact. When a threat actor understands the underlying technology used by cloud service providers, they can accomplish a great deal if they can gain access to credentials that have the right permissions.

During the past year, Unit 42 responded to multiple cases where the SugarCRM vulnerability CVE-2023-22952 was an initial attack vector that allowed threat actors to gain access to AWS accounts. This was not due to a vulnerability in AWS, and it could have happened with any cloud environment. Instead, the threat actors took advantage of misconfigurations to expand their access after initial compromise.

This article maps out various attacks against AWS environments following the MITRE ATT&CK Matrix framework, wrapping up with multiple prevention mechanisms an organization can put in place to protect themselves. Some of these protections include taking advantage of controls and services provided by AWS, cloud best practices, and ensuring sufficient data retention to catch the full attack.

The complexity of these attacks shows how it’s important to set your logging and monitoring to detect any unauthorized AWS API calls, even if they’re seemingly innocuous. If threat actors are allowed to gain a foothold, this can lead to much more daunting activity that is not always traceable. One size does not fit all in cloud security, but these attacks highlight key areas to focus on to make sure you're ready to defend against those attacks when they come.

Palo Alto Networks customers receive protections from the attacks described in this article in the following ways:

- Organizations can engage the Unit 42 Incident Response team for specific assistance with this threat and others.

- Prisma Cloud can provide alerting and mitigation solutions for the use-cases reported within this blog.

- Next-Generation Firewall with the Advanced Threat Prevention security subscription can help block the attacks.

| Related Unit 42 Topics | AWS, Cloud |

Table of Contents

MITRE ATT&CK Matrix

Case Walk Through

Initial Access – CVE-2023-22952

Credential Access

Discovery

Lateral Movement/Execution/Exfiltration – RDS

Lateral Movement/Execution – EC2

Privilege Escalation – Root

Persistence – Regions

Defense Evasion

Remediation

Access Keys

Least-Privileged IAM Policies

Monitoring Root

Logging and Monitoring

Conclusion

Product Protections

Indicators of Compromise

MITRE ATT&CK Matrix

We’re framing the walk-through for these incidents with the MITRE ATT&CK Matrix, which is comprised of fourteen different tactics that describe the various components of a cybersecurity attack. With the various cases we responded to, nine of those fourteen tactics described the threat actor activity. Those nine were initial access, credential access, discovery, lateral movement, execution, exfiltration, privilege escalation, persistence and defense evasion.

Case Walk Through

Initial Access – CVE-2023-22952

The initial attack vector of these AWS account compromises was the zero-day SugarCRM vulnerability, CVE-2023-22952. SugarCRM is a customer relationship management platform that focuses on cross-team collaboration. The product has users in many different verticals due to their wide range of product features.

CVE-2023-22952 was published by NIST National Vulnerability Database on Jan. 11, 2023, with a base score of 8.8. This vulnerability allows threat actors to inject custom PHP code through the SugarCRM email templates module due to missing input validation.

To understand why the threat actors targeted SugarCRM for these attacks, it’s helpful to know that there is a wide range of sensitive data such as email addresses, contact information and account information in SugarCRM customer databases. If it was compromised, threat actors would either choose to sell this information directly or extort their victims to get more money.

By leveraging this vulnerability in SugarCRM, a threat actor can gain direct access to the underlying servers running this application due to the remote execution component of the vulnerability. In the cases we responded to, these servers were Amazon Elastic Cloud Compute (EC2) instances with long-term AWS access keys stored on the hosts, allowing the threat actors to expand their access. Since these organizations were hosting their infrastructure in the cloud, it opens different attack vectors for the threat actors than would be present with on-premises hosting.

Credential Access

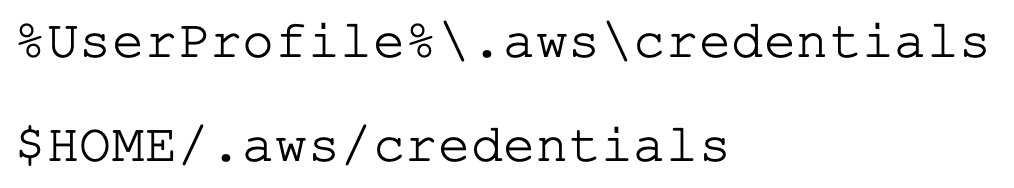

Once the threat actors gained access to the EC2 instances, they successfully compromised long-term AWS access keys that existed on the host. Regardless of whether the computer exists on-premises or in the cloud, if a person uses the AWS command-line interface (CLI), they can choose to store temporary or permanent credentials used for the authentication within a credentials file stored on the host (as shown in Figure 1 below, which includes the file path).

In the cases we observed, these plain-text credentials existed on the compromised hosts, which allowed the threat actors to steal them and start using the access keys for discovery activity.

Discovery

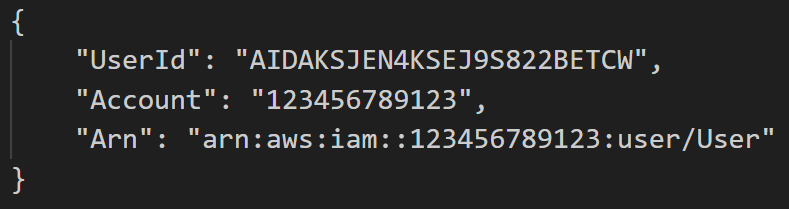

Before the threat actors performed any scanning activity, they first ran the command GetCallerIdentity. GetCallerIdentity is the AWS version of whoami. It returns various information about the entity that performed the call such as the user ID, account and Amazon Resource Name (ARN) of the principal associated with the credentials used to sign the request, as shown in Figure 2. The user ID is a unique identifier of the entity that performed the call, the account is the unique 12-digit identifier of the AWS account the credentials belong to, and the ARN includes the account ID and human-readable name of the principal performing the call.

Once the threat actor knew a little more about the credentials they compromised, they began their scanning activities. They utilized the tools Pacu and Scout Suite to gain a better understanding of what resources existed within the AWS account. Pacu is an open-source AWS exploitation framework, and it is designed to be the Metasploit equivalent in the cloud. Scout Suite is a security auditing tool used for security posture assessments of cloud environments.

In some of the cases we responded to, we saw Pacu already existed on hosts from previous penetration tests. Scout Suite was not something we saw downloaded onto the compromised EC2 instances, but we knew it was used based on the user agents associated with the threat actor activity. Both of these tools provide a lot of information for threat actors to get a lay of the land for the AWS account they’ve compromised.

In the cases, these tools scanned a variety of traditional services such as the following:

The threat actors also performed other discovery calls against services that would not necessarily be expected that provided helpful information to the attackers, such as the Organizations service and Cost and Usage service.

AWS Organizations provides companies with a centralized place to manage multiple AWS accounts and resources. When reviewing the threat actor activity in the CloudTrail logs, three Organizations API calls stood out. The first call was ListOrganizationalUnitsForParent, which lists out all the Organizational Units (OUs).

From there, the threat actors ran ListAccounts which returns all the account IDs associated with each of those OUs. The final call that provided the threat actor with the most useful information was the DescribeOrganization API call. This event returns the master account ID as well as the master account email address associated with that account. With that information, the threat actors have enough to attempt to log in as the Root user for that account.

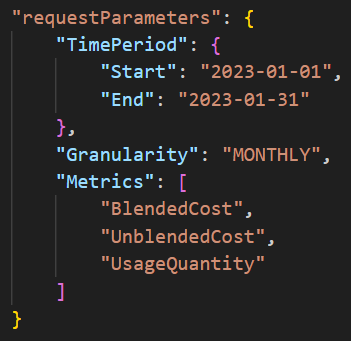

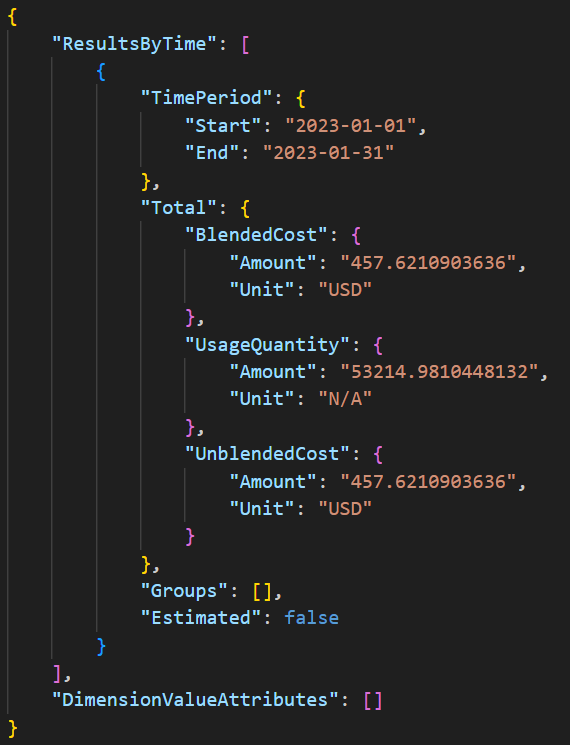

The final discovery call of interest involved the Cost and Usage service. The threat actors performed various GetCostandUsage calls (shown in Figure 3) and the response returned information about the general costs within the compromised account (shown in Figure 4).

Defenders need to be aware that threat actors can determine how active an account is by understanding the cost within a cloud account. If the total cost in an account is large, it might be easier for them to spin up new resources undetected, because the cost might not stand out.

On the other hand, if there is very little spending in an account, a couple new resources could stand out a lot more. Account owners with less spending might also have tighter notifications around cost, which would potentially trigger alerts when the threat actors create new resources.

Both the Organizations and Cost and Usage API calls are great examples of how the attack surface is different in the cloud. By using these innocuous looking API calls, threat actors gained a ton of information about the account structure and usage without performing a lot of suspicious activity that might trigger an alert.

Lateral Movement/Execution/Exfiltration – RDS

In the incidents we observed, once threat actors finished scanning the environment, they had enough information to narrow their activity from discovery across the whole account to taking actions on various services starting with the Relational Database Service (RDS). The threat actors moved laterally from the compromised SugarCRM EC2 instances to the RDS service and started executing commands to create new RDS snapshots from the various SugarCRM RDS databases. The creation of these snapshots resulted in no downtime of the original RDS databases.

From there, the attackers modified pre-existing security group rules that already allowed SSH inbound, and they added port 3306 for MySQL traffic. The threat actors then moved to exfiltration, creating brand new databases from the snapshots, making them public and attaching the modified security groups. Finally, they modified the newly created RDS databases by changing the master user password, which would allow them to log in to the databases.

To understand whether any exfiltration of data occurred, in the cases that had virtual private cloud (VPC) flow logs enabled, we could use the logs to see how many bytes of data left the environment. With the cases that did not have VPC flow logs enabled, we were limited in our findings of data exfiltration.

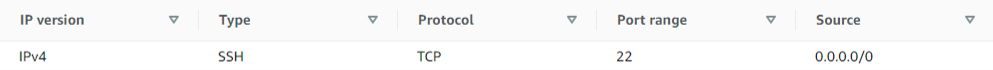

Lateral Movement/Execution – EC2

After the RDS activity, the threat actors again moved laterally back to the EC2 service and made some changes. The first thing the threat actors did was create new Amazon Machine Images (AMIs) from the running SugarCRM EC2 instances, and from there they ran the ImportKeyPair command to import their public key pair that they created with a third-party tool. With these tasks complete, the threat actors proceeded to create new EC2 instances. The threat actors also attached existing security groups to the EC2 instances that allowed inbound port 22 access from any IP address, as shown in Figure 5.

The threat actors created EC2 instances in the same regions that the organizations used for the rest of their normal infrastructure. They also switched regions to a geographically new area, and created a new security group that allowed port 22 SSH traffic from any IP address. The threat actors then imported another key pair. Since the threat actors switched to a different region, the key pair had to be reimported even if it was the same key pair used in other regions.

After finishing the setup, they created a new EC2 instance, but this time they used a public AMI available on the AWS Marketplace. This EC2 instance activity shows the importance of enabling security services such as GuardDuty in all regions, to have visibility into all that is happening within an AWS account. As a proactive measure, organizations can disable unused regions as well.

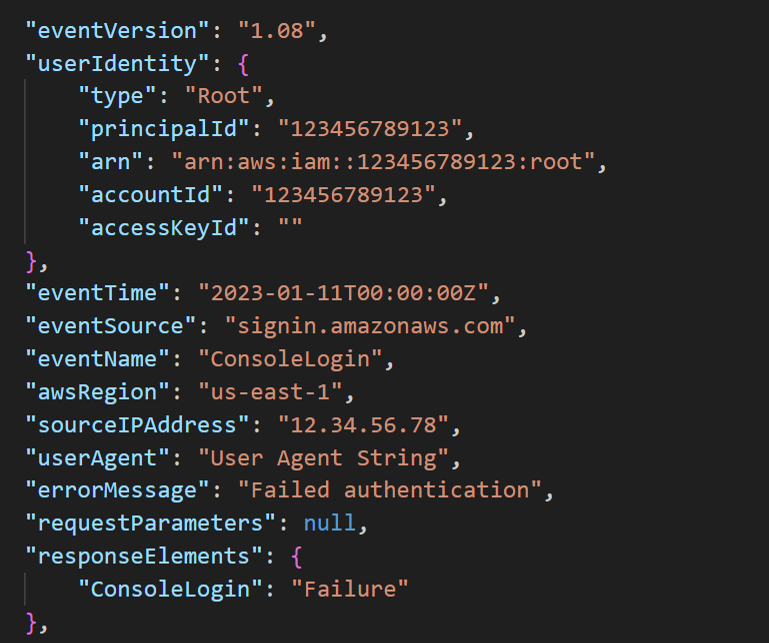

Privilege Escalation – Root

For the privilege escalation portion of these attacks, the threat actors did not attempt to create new IAM users like we have seen in other cases. They instead opted for attempting to login as the Root user. Despite using information they obtained from the Organizations calls made during the discovery phase, the threat actors still failed to successfully log in as the Root user. Root login attempts are fairly noisy, so these failed Root logins stood out in the CloudTrail logs, as shown in Figure 6.

Persistence – Regions

Beyond attempting to log in with the Root account, the threat actors did not try much in the way of persistence. The clearest attempt at persistence was the creation of EC2 instances in different regions than the organizations normally used to host their infrastructure. Similar to the Root login attempts, these new EC2 instances stood out in the CloudTrail logs. However, it can be easy to miss stuff when reviewing resources in the console, as it's a fair amount of work to switch regions and track down all resources created, as cloud environments get larger.

Defense Evasion

Once a threat actor compromises an AWS account, they have a finite amount of time before the account owners detect that they have an issue. In order to stay under the radar, the threat actors deployed resources in non-standard regions. However, they also turned the EC2 instances on and off throughout their time in the environments.

There are a couple of reasons why a threat actor might choose to do this. The first reason is to decrease their visibility. On the EC2 instance page in the AWS console, it defaults to showing only running EC2 instances. Unless a user is actively trying to review non-running EC2 instances, at an initial glance, the new EC2 instances created by the threat actors would be missed once they are placed in a stopped state.

The second reason they might choose to do this is that stopping these resources also avoids incurring extra costs in the organization’s account. If the organizations have tight notifications around costs, threat actors stopping the resources they created minimizes costs and helps prevent triggering a cost alert, which is another way they could evade defenses.

Other than creating resources in different regions and stopping the resources they created, the threat actors did not attempt other defense evasion techniques such as stopping CloudTrail logging or disabling GuardDuty.

Remediation

Access Keys

There are four main remediation actions that organizations can take to protect themselves against these types of attacks in the future. The first one revolves around access keys. It’s vital for organizations to protect their access keys, as we often see them being the root cause of AWS compromises.

There is never a good reason to use long-term access keys on EC2 instances. Instead, use EC2 Roles and the temporary credentials that are present in the Instance Metadata Service (IMDS). Also, make sure to only use IMDSv2, which protects against server-side request forgery (SSRF) attacks.

We recommend creating a cleanup process for any long-term access keys stored in the credentials files on the hosts. This can be accomplished by asking users to clean up those files when they have completed their work, or by creating an organizational-level process that automatically cleans up these files.

We also recommend that the access keys are rotated and deleted on a schedule. The longer an access key lives, the more chance it has of being compromised. Consistently rotating them and deleting unused keys proactively protects the AWS account. This whole process can be automated and helps keep access key security in check.

Least-Privileged IAM Policies

The only reason that these threat actors were able to accomplish all that they did in these attacks was because of the expansive permissions that the organizations gave to the IAM User principal on the SugarCRM host. These IAM Users that were present on the hosts needed some AWS permissions, but those should have been narrowly scoped to only include exactly what the application using the permissions needed. And these organizations were not alone in this situation – according to our Cloud Threat Report, Volume 6, 99% of cloud users, roles, services, and resources were granted excessive permissions, which were left unused.

You can use AWS Access Analyzer to examine the historical usage of APIs by a particular IAM principal and automatically generate an access policy that restricts its access to only those APIs that it has used in the time period of your choice.

It might be easier to write overly permissive policies, but it is certainly worth the effort to write narrowly scoped permissions to better protect your AWS account.

Monitoring Root

Another remediation step we recommend to these organizations is to set up monitoring around the Root account. This account should only be used in an environment for a couple account management tasks that require Root, which maintains this as a high-fidelity alert to help secure the most valuable account. We also recommend always enabling multifactor authentication on Root and making sure it is protected with a long password.

Logging and Monitoring

The final remediation we recommend to these organizations is to make sure they have the correct logging configured. CloudTrail and GuardDuty should both be enabled in all regions and logs sent to a centralized location.

When it comes to GuardDuty, the alerts should be sent to a team that will respond based on the alert severity. In our cases where the organization had GuardDuty enabled, we saw that GuardDuty caught these access key compromises fairly early on in the attack. This is an easy way to help protect your accounts.

We also recommend for organizations to enable VPC flow logs to help catch any data exfiltration that might take place. These logs are extremely helpful when troubleshooting network connectivity issues. And with all of these different services, it’s important to make sure to have a good retention period for the data. Regardless of the environment, compromise can happen anywhere, and it’s vital to make sure logs are retained long enough to catch the full attack.

Conclusion

Even though the threat actors were able to accomplish a lot in these attacks, we saw that there’s some great remediation steps organizations can put in place to better protect themselves. Since access keys are the most common initial attack vector, try to avoid the use of long-term access keys when possible. In AWS, this means using EC2 Roles, IAM Roles Anywhere or Identity Center integration for developer workstations. Another layer to protect those keys is setting up monitoring around abnormal usage. With these attacks, the threat actors performed abnormal API calls, which is all detectable with long-tail log analysis.

It’s also imperative to do basic least-privilege analysis so that code running inside or outside the cloud has only the permissions it needs to do its job.

You always want to make sure that you’re monitoring your cloud accounts for abnormal activity in addition to monitoring access keys. In AWS this can look like monitoring various services such as CloudTrail, VPC flow logs and S3 server access logs. If services within your cloud account are being accessed by or reaching out to new and unusual IP addresses over abnormal ports, you want to make sure your monitoring is configured to alert on this activity. Also, if your organization has sensitive data in S3 buckets, monitoring S3 server access logging to note abnormal calls to the bucket helps proactively find attacks.

And finally, the threat actors were able to accomplish all that they did in these cases because of the lack of granular permissions. If these compromised access keys that belonged to IAM Users had fewer permissions, that would have stopped the threat actors in their tracks.

Product Protections

Palo Alto Networks customers can leverage a variety of product protections and updates to identify and defend against this threat.

If you think you may have been compromised or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America Toll-Free: 866.486.4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- EMEA: +31.20.299.3130

- APAC: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

Prisma Cloud

Prisma Cloud can provide alerting and mitigation solutions for the use-cases reported within this blog in the following ways:

- Prisma Cloud Anomaly Policies can be deployed to detect instances running in out of use AWS regions, as well as detecting suspicious IAM credential usage through AI/ML algorithmic functionality.

- Prisma Cloud’s Attack Path Policies can also detect lateral movement and privilege escalation attacks against the EC2 instances described within this blog.

Prisma Cloud uses the MITRE ATT&CK framework as the guiding principle for developing detection and risk mitigation capabilities.

Next-Generation Firewalls and Prisma Access With Advanced Threat Prevention

Next-Generation Firewall with the Advanced Threat Prevention security subscription can help block the attacks via the following Threat Prevention signature: 93591.

Indicators of Compromise

IPs:

- 13[.]90.77.93

- 31[.]132.2.66

User Agents:

- Boto3/1.26.45 Python/3.9.2 Linux/6.0.0-2parrot1-amd64 Botocore/1.29.45

- Boto3/1.7.61 Python/3.5.0 Windows/ Botocore/1.10.62

- aws-cli/1.19.1 Python/3.9.2 Linux/6.0.0-2parrot1-amd64 botocore/1.29.58

- aws-cli/1.18.69 Python/3.5.2 Linux/4.4.0-1128-aws botocore/1.16.19

- Scout Suite/5.12.0 Python/3.9.2 Linux/6.0.0-2parrot1-amd64 Scout Suite/5.12.0

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh