2023-11-10 21:1:24 Author: therecord.media(查看原文) 阅读量:10 收藏

Hadas Kalderon grew up in Kibbutz Nir Oz, not far from the border with Gaza. She said it was always a beautiful place, full of flowers and animals. So beautiful that after an education abroad — she has French and Israeli citizenship — she returned to raise a family there.

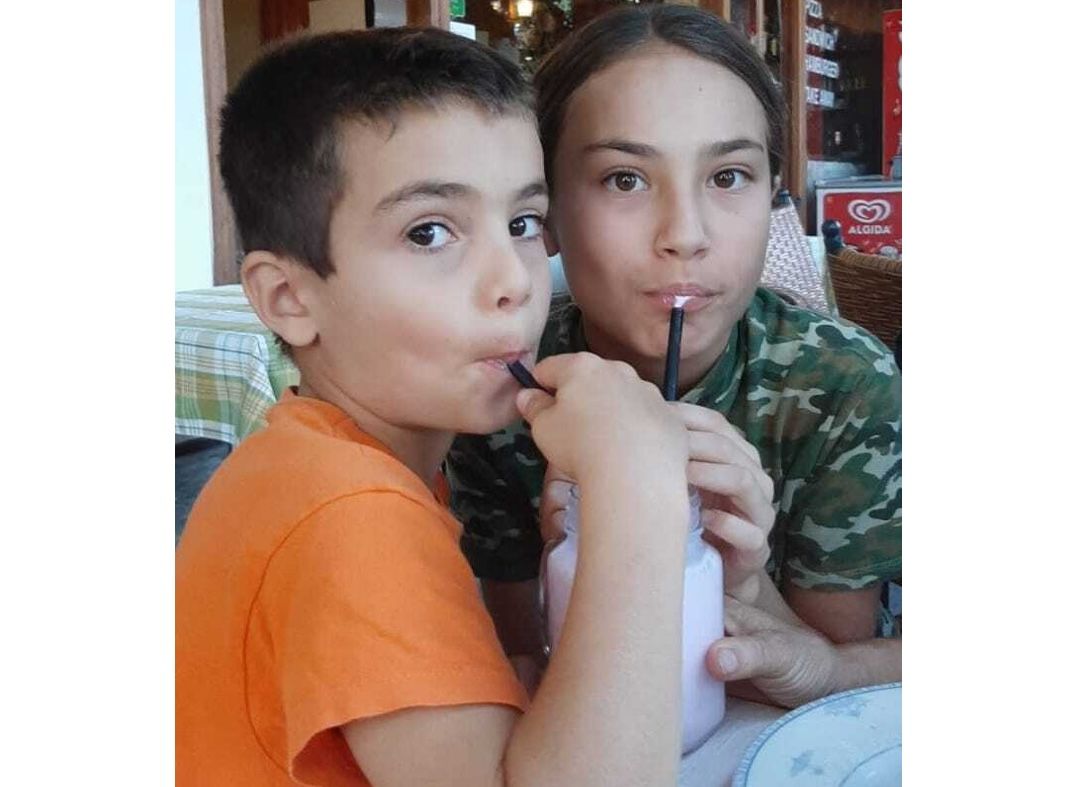

She has four kids and her youngest, Erez, is 12. “He loves to ride horses, he loves to play football and ping pong,” she said recently. “He loved computers, like all children, you know, and he loved to laugh. He laughed a lot. He had a great sense of humor.”

She sent us videos of him. One at a local fair crashing a bumper car into another; a short of the family sending a greeting to someone, where he was mugging for the camera; and another of Erez and his father and sister flying a remote controlled airplane over a green velvety field near their home.

“Their father used to teach them to fly these small airplanes,” she said. “He built them and then he made them fly.”

October 7th, she said, started like any other Saturday. “About 6:30, I wake up … and then by 7 o’clock, 7:30, I start to hear them,” she said, referring to the Hamas gunmen who roared into Nir Oz. “I can hear Arabs shouting and shooting and shooting everywhere.””

She did what they had always done: She ran to the safe room in the house. “It's a normal small room, but it's safe [from] bombs,” she said. “But it can't be locked from inside. And all the members in the kibbutz, 400 members, [are in the] same situation as me. Nobody can lock the door.” That’s because she said, no one ever imagined a scenario in which the people trying to get in didn’t want to help you, they wanted to kill you.

“I can hear them behind my door. Ta ta ta ta ta,” she says, making a clicking sound with her tongue for the sound of machine gun fire. “Talking, talking. Al Akbar. Ta ta ta ta ta. Arabic, you know. I used to love this language. I used to love it.”

She put her body against the door. Held it closed with her legs and did everything she could to prevent them from entering the room. She held them off for three hours until they finally went away.

Erez and one of her daughters, Sahar, 16, had been spending the night with their father, her ex-husband. He lives in a house in Kibbutz Nir Oz, less than a mile away. Hadas sent a text to see if everyone was OK. She got a message from the father around 8:30.

“The terrorist is in our house,” it read. “We jumped from the window. We’re hiding in the bushes.”

And Kalderon said she wrote back right away, “‘Oh no. Oh my God. Don't do that. Go back to the shelter immediately.’ But I don't think he saw this message.”

A short time later she got a message from Erez. “He tell me, ‘Mom, Mom, be quiet, be quiet, I love you.”

Erez Kalderon, left, and sister Sahar. Image: Hadas Kalderon

Erez Kalderon, left, and sister Sahar. Image: Hadas Kalderon

That was the last she heard until a few days later. That’s when her Erez appeared in a completely different kind of video. Hamas had posted it on social media and it showed an armed Hamas gunman manhandling him. The boy looks stoic as the fighter pulls him around by the shoulder. Kalderon knows the video is out there. It’s gone viral. But she won’t watch it. “I don't want to see my son, my small baby, helpless,” she said. “So terrified. I don’t want to see that.”

There has been no word since. His sister and his father have gone missing too.

That video, and hundreds of others like it, posted by Hamas in the days after the massacre, have provided digital clues, a gossamer trail that has helped investigators and volunteers in Tel Aviv to identify thousands of people who appeared to go missing in the confusion after the attacks. At last count, some 1,400 Israelis were killed, thousands were wounded and some 240 more were kidnapped and taken back to Gaza — and it has been difficult to figure out who is who and to connect a name with a face.

In the fog of what is now a war between Israel and Hamas, after a month of Israeli airstrikes that have educed much of northern Gaza to rubble, one of the first things lost on both sides has been the ability to communicate — emotionally, politically and even technologically.

Israelis have struggled to identify the missing, the dead and the abducted. Palestinians living in the Gaza Strip have had to contend not just with bombs but with internet and informational blackouts that have prevented anyone inside and outside of Gaza to take full measure of what is transpiring.

For families like the Kalderons, two ordinary people stepped into the breach. One Israeli professor and the other a Palestinian refugee who both leveraged their social networks and some cutting edge technologies to try to sort through the confusion that has followed the mourning and outrage of the unfolding events.

Digital clues in the ‘Gaza envelope’

About a hundred miles north of Kibbutz Nir Oz, in Tel Aviv, a woman named Karine Nahon was thinking about how distressing it must be for families like the Kalderons who were missing loved ones, with so little information to go on. It turns out that information was Nahon’s specialty: she is a professor of politics of information at Reichman University in Israel.

“In my usual daily life I am a professor,” she said, adding that she is also one of the most prominent voices in Israeli civil society today. For much of this year she has been a leader in the movement that has brought millions into the streets to protest against Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s efforts to reduce the authority of the nation’s Supreme Court and, she adds, to dismantle some of Israel’s democratic institutions. “Americans have reduced it down to the Supreme Court but it is much broader than that.”

Because she had been leading the protests for the past nine months, she had a network ready to go. She controlled dozens of WhatsApp channels that connected her to tens of thousands of protesters who had joined her in the streets since the spring. Soon after the October 7th attacks she put out a call asking if anyone wanted to help with a different kind of grassroots campaign: She sought help identifying the thousands of people who were unaccounted for in the confusion after the attacks.

“And my WhatsApp really exploded,” she said.

Tech bros, academics and ordinary citizens immediately responded, and she made a point of saying that anyone who was willing to help was welcome — it didn’t matter if you were a humanities professor, a coder, or a doctor of philosophy.

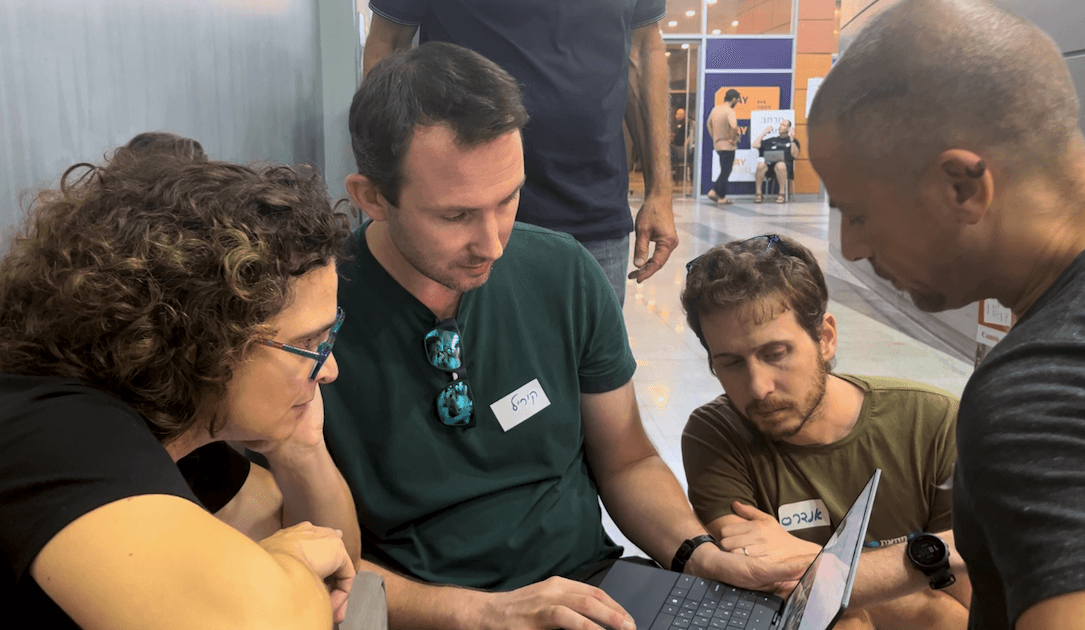

For the past four weeks, Nahon has been sitting in a conference center in Tel Aviv with 1,500 volunteers following digital clues that will allow them to put a name to the face of those who either were killed, survived or were abducted during those initial attacks. And to do that they needed to figure out who was in the area at the time.

“We didn't even know what the starting point was,” Nahon said later. “We didn't know what we're talking about. Who knew who was exactly in the South?” Who might have been near the border — what Israelis call the Gaza Envelope — that morning? It’s like saying how do you identify everyone who went to Central Park on a Saturday.

Karine Nahon, with megaphone, instructs volunteers in the effort to identify Israelis who were kidnapped, killed or unaccounted for after the October 7 attacks. Image: Amit Farbman

Karine Nahon, with megaphone, instructs volunteers in the effort to identify Israelis who were kidnapped, killed or unaccounted for after the October 7 attacks. Image: Amit Farbman

Compiling a list

They decided to start with the military, specifically an Israeli search and rescue unit known as the Home Front Command. “We thought they probably had the right list” to start with. “But very fast, we found out that the list was full of noise,” Nahon said, adding that was a non-starter for them. “You have to understand, you can't make mistakes here. Because every person counts.”

So they started compiling their own list and created a website to try to get more information from the public. That turned out to be inspired. People looking for loved ones provided volumes of information. Just consider the Nova music festival, that giant rave in the desert about three miles from the Gaza border that was a target of the Hamas assault. As many as 4,000 people were supposed to attend and because it wasn’t a formal ticketed event, it was nearly impossible to figure out who exactly was there, camping and milling in and out.

That’s where Nahon and the volunteer team started. They began cross referencing names with festival organizers, cities and the network of nearby kibbutzim to start winnowing down the list . “It was really crafting a kind of a picture from so many sources of information,” Nahon said. “It's an investigative effort.”

They began to scour videos and images that had been uploaded — source photographs on the fly. These weren’t images with two eyes and two ears, with someone smiling into the camera. These were blurry or taken from the side. So Nahon’s team began looking for ways to decode them, they found people in their pool of volunteers who could write algorithms to unblur photographs or rework facial recognition software so it could identify half a face, and then they started looking beyond faces to other clues.

“We began to identify a person by the fabric of his underwear,” Nahon said. “We identified people by looking at their tattoos, by looking at the unique properties of their body. So it's, it's a flip, right? Usually you'd identify the face and then you identify the body, but here we did something opposite.”

Then they cross referenced all the information they’d gathered on potential victims with videos Hamas had posted themselves on the 150 channels they have on Facebook, TikTok and other social media platforms. “We tried to find out whether anyone on our list could be found in the videos with the terrorists,” she said. “It was like assembling a dossier on everyone who was missing.”

They’d get a name, try to identify all the pictures they could of that person, train facial recognition software on it, and then a human, one of the 1,500 people on her team, would check it all. And if they found a match, they would pass that information to the authorities.

From scholars’ heads into the real world

And because the team was all in one room, there were quick ways to solve what might seem like intractable problems. That’s how they were able to solve that blurry photo problem. With all those random people in one room, when they asked if anyone had a solution some of the scholars actually did.

“There were technologies that were developed in scholars’ heads,” Nahon said. “They were in compartments sitting in universities, but never were implemented, so we kind of had like this big bang, they were able to implement things that that so far were in theory only.”

Between the social media feeds, the Hamas posts, the improvised technologies and all that people-power, Nahon’s team ended up identifying just about everyone at the Nova music festival. It was, Nahon said, the ultimate marriage of man and machine.

Karine Nahon, left, and volunteers work to identify Israelis missing in the October 7th attacks. Image: Amit Farbman

Karine Nahon, left, and volunteers work to identify Israelis missing in the October 7th attacks. Image: Amit Farbman

But in a way, the most improbable thing about it was that it was led by Karine Nahon at all, and she told the volunteers as much. “In normal times,” she had told them, “we wouldn’t have the right to do even a tenth of what we’re doing here both ethically and legally.”

That’s because this was a giant project of internet scraping, an effort that trampled on the privacy of thousands of people who, by no fault of their own, went missing on a terrible day in Israel. It’s the kind of project that went against everything Nahon stood for as a digital rights activist.

“I'm the one who's all the time complaining, even appealing to the high justice court for breaches of privacy,” she said. “And for this I switched my hat to 180 degrees to get information, any information, about those people. We were in a situation where time was running out and we couldn’t wait. It was passing a red kind of line for me, one that I don’t cross. But it was obvious this time, we needed to do that.”

‘Unplugging’ the internet in Gaza

In Gaza, where Israeli ground troops are now fighting, efforts of technological resilience and improvisation are happening for another reason: simple communication. The connectivity that many people take for granted all but disappeared — almost overnight.”

Mohammad Abuajwa is an English teacher in Central Gaza, in a city called Deir el Barah. When the war began he was about to go to Germany to begin work on a graduate degree. We wanted to talk to him on the phone, but the Internet there was so patchy we couldn’t get through.

So we had him record answers to questions on his phone and send them to us when there was enough internet to do so. He recorded one while he was standing at a window looking out onto the rubble that used to be the apartment building next door. Israeli airstrikes hit the place about two weeks earlier. He said trucks had pulled up front in a bid to extract anyone who had been caught underneath. “A lot of people died and some of them were never found,” he said, sighing. “So it’s pretty, pretty terrible.”

The internet blackouts — and the sinking feeling that people in Gaza were suddenly cut off from the world — began a short time after that. Abajwa said that the first time, everything went dark for 36 hours. And he said it was frightening for anyone who had any loved ones in Gaza.

⚠ Update: Metrics show that internet connectivity is being restored in the #Gaza Strip after Sunday's near-total telecoms blackout, the second-longest observed since the onset of the present conflict with Israel; overall service remains significantly below pre-war levels 📈 pic.twitter.com/oHkzNkSxUX

— NetBlocks (@netblocks) November 6, 2023

“Imagine if you were abroad and you had a family here in Gaza,” he said. “And that internet connection was stable for some point, but then suddenly, for 24 hours or so, [it] goes down." People outside Gaza immediately assumed the worst. “Your family and friends assume you were bombed here in Gaza. They thought we were under the rubble,” he said.

When the internet came back on, his friends and family flooded him with calls. “We comforted them,” he said. “We told them that, hey, everything is fine.” The next time the internet disappeared was a couple of days before we interviewed him. “And it was quite a bit shorter, the Wi-Fi came back quickly. It almost feels like someone is pulling the plug and plugging it back in whenever they please.”

Fiber optic hangups

Gaza is about twice the size of Washington, D.C., and its telecom provider, Paltel, started in the 1990s. Its very existence was set out as part of the Oslo and Paris peace accords between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization. They were supposed to be part of an effort that would allow Palestinians to manage their own infrastructure: roads, water, telecoms.

But Paltel’s fiber-optic cables run through Israel, said Helga Tawil-Souri, an associate Professor of media, culture and communication at New York University. “So it's easy to be able to kind of shut the internet down.”

She’s been watching the blackouts in Gaza and she says the outages there are about a lot more than bombing campaigns. “There has been bombing of cell towers but that in and of itself is not enough to just shut down in the way that we saw … that requires the metaphorical flip of a switch. So, it is. It is a purposeful kind of shutting off.”

That said, even when the Internet is not being intentionally turned off, even at the best of the times, connectivity in Gaza is patchy. And Tawil-Souri says that has more to do with the technology itself. “Palestinian providers are still functioning on a network that was initially able to sustain about 200,000, maybe 300,000 cellular users on the older 2G network,” she said.

She says it is, among other things, a math problem. Today the network is being used by a million more users, but the infrastructure is so old it was built for flip phones. What that means, she said, , is that there is no signal because too many people are trying to use the network at the same time, or you get dropped calls. “They still have dial-up modems there,” she said.

Abuajwa, the English teacher in Gaza, said when the internet disappears it’s unnerving. “When we don't know what's going on, it’s more scary, basically,” he said. “This lack of internet connection and so on, no one knows about [what Israel is doing]. And that's the issue to begin with. No one knows how bad the situation in Gaza [is] because they can't know when there isn't anyone to report.”

‘Leap of faith’

But it turns out a lot of people were concerned about that, too, including Bashar Shaheen, a Jordanian marketing executive living in Saudi Arabia who had been watching events unfold in Gaza — the bombings, the internet blackouts — and he thought there must be something he could do.

It turns out that he, like Karine Nohan, had quite a history of organizing people, though in his case it was on behalf of Palestinians. Back in 2021 he had created a translators movement, an effort to ensure that the world knew what was going on in Gaza. “I collected more than 300 people that speak all the languages of the world, just to translate the news [coming out of Gaza] to reveal the truth to the world.”

So when he saw the communications issues that Gaza was having in the early days of the war, he was trying to come up with a workable solution. Some people in his circles were saying they should try to get Starlink, Elon Musk’s satellite network, into Gaza. But Bashar didn’t think that would be an option.

“I tweeted about it. I said, ‘Uh, listen guys, this is impossible to be happening right now because Gaza is closed. Nobody is allowed to enter, nobody is allowed to go out of it. So, the Starlink thing won't happen.’”

Shaheen said he’s not a particularly techie guy, but he did think there was one technology that might provide a solution: an eSIM.

The technology has been around since 2016, but has only become popular in the last couple of years. Like a regular SIM card it holds your phone number and your account information, but to install it you don’t need to go to a store, you just need to scan a QR code with your smartphone. Shaheen figured it would be able to turn those non-functioning PalTel phones into devices that could connect to a different network that is online and use that one instead.

“So people closer to the northern part of Gaza connect to the Israeli cellular towers and people closer to Rafah, which is in the south, connect to the Egyptian towers,” he said. What’s more, eSIM cards are pretty inexpensive. You can get one that lasts a week for about $5 or a higher end one with more connectivity and more time for about $30.

So Shaheen tweeted out his plan and asked if anyone in Gaza might want a couple of eSIMs. “And I'll be completely honest, I didn't know that the eSIMS initiative would work,” he said. “So, uh, I took a leap of faith.”

— Bashar. (@BasharChaheen) October 28, 2023الحمدلله،قدرنا نوصل الشرائح الإلكترونية وبتعمل بشكل ممتاز مع أخواننا في قطاع غزة. الصحفيين الآن لديهم وصول للإنترنت. بفضل جهودكم.

We managed to distribute the eSims to the journalists in Gaza and they’re working perfectly. They thank you for your support to them. Alhamdulellah!

The next morning his social media account was filled with barcodes for donated eSIMs he could send to Gaza. “When the people knew that, that one actually worked, they started sending me tens,” he said. “Then it turned to hundreds. Then it turned to thousands. So many, we couldn't keep up with the numbers.”

A little more than a week into the project he had more messages in his inbox than he had time to reply to. “We’re sending thousands of eSIMS to Gaza,” he said. “People actually found my account on Instagram and flooded me there. Now they are sending messages and eSIMs to me on Twitter too.”

At first he was just sending the eSIMs to journalists and emergency medical personnel. Now, he says, anyone who asks can get one, and he has recruited a couple of friends to help him manage all the requests.

“There have been a lot of emotional messages telling us that this eSIM might have provided us with one last call to our loved ones outside of Gaza, and just to tell them goodbye,” he said.

It’s not a perfect solution. We spoke to half a dozen people in central Gaza who said they were too far away from working networks in Egypt or Israel for the eSIMS to work. But in a time of war, when everything seems so unsure, just being able to hear a familiar voice on the other end of the phone can be a welcome lifeline.

Get more insights with the

Recorded Future

Intelligence Cloud.

No previous article

No new articles

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh