- Cisco Talos has recently observed an increase in activity conducted by 8Base, a ransomware group that uses a variant of the Phobos ransomware and other publicly available tools to facilitate their operations.

- Most of the group’s Phobos variants are distributed by SmokeLoader, a backdoor trojan. This commodity loader typically drops or downloads additional payloads when deployed. In 8Base campaigns, however, it has the ransomware component embedded in its encrypted payloads, which is then decrypted and loaded into the SmokeLoader process’ memory.

- 8Base’s Phobos ransomware payload contains an embedded configuration which we describe in this blog. Besides this embedded configuration, our analysis did not uncover any other significant differences between 8Base’s Phobos variant and other Phobos samples that have been observed in the wild since 2019.

- Our analysis of Phobos’ configuration revealed a number of interesting capabilities, including a user access control (UAC) bypass technique and reporting victim infections to an external URL.

- Notably, in all samples of Phobos released since 2019 that we analyzed, the same RSA key protected the encryption key. This led us to conclude that attaining the associated private key could enable decryption of all these samples.

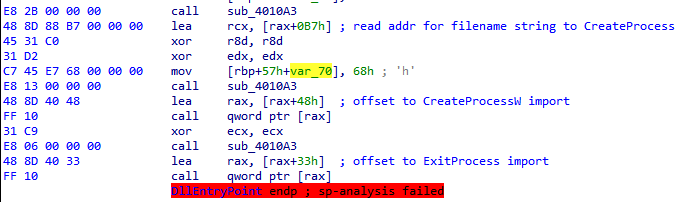

We won’t use this space to provide a full overview of SmokeLoader (Malpedia has the basics), but we would like to show how reverse-engineers can reach the final payload. In this example, we’ll use the sample 518544e56e8ccee401ffa1b0a01a10ce23e49ec21ec441c6c7c3951b01c1b19c, but any recent 8base sample will have the same ransomware binary payload in the end. This process requires the execution of the malware in a controlled environment under a debugger like x32dbg.

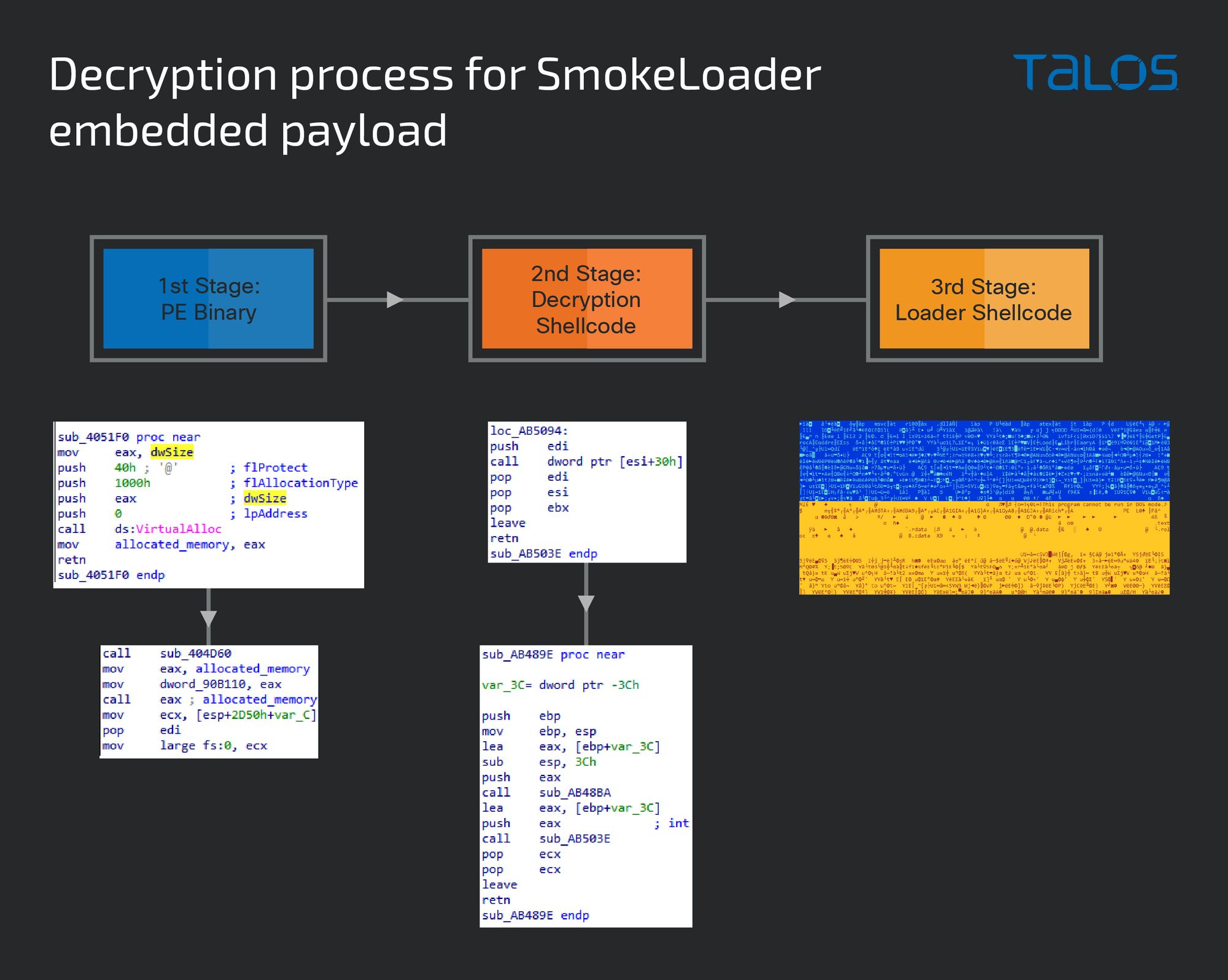

SmokeLoader malware decrypts its payload in three stages. The first contains many random API calls to obfuscate the execution flow, while the other two involve shellcode stored in allocated memory. The final binary is exposed in the third stage, where a binary copy of the PE (Windows Portable Executable) data in that memory block gives the final payload in its original form.

In the first stage, enabling a breakpoint at VirtualAlloc or VirtualProtect and checking its arguments should reveal the address where the next stage will be decrypted. This memory location will then be called at the end of the entry point (EP) function, as shown above.

On the second-stage shellcode, following the second call in the function called from the entry point leads to the call to the second allocated memory with the third stage. Once the third stage is reached, that memory area should contain the unpacked binary (PE) which can then be exported to a file and analyzed.

The final payload hash extracted by this method is 32a674b59c3f9a45efde48368b4de7e0e76c19e06b2f18afb6638d1a080b2eb3.

Our analysis of Phobos uncovered a number of features that enable operators of the ransomware to establish persistence in a targeted system, perform speedy encryption, and remove backups, amongst other capabilities. Phobos is a typical ransomware capable of encrypting files both in local drives as well as network shares. In our FY23 Q2 Talos Incident Response Quarterly Report, we detailed how the 8Base group used their Phobos variant after installing AnyDesk to enable remote access to the machine as well as perform credential dumping via LSASS. These stolen credentials were later used to elevate privileges, exfiltrate data and run the ransomware module.

Talos has observed the following features present in the malware code:

- Full encryption of files below 1.5MB and partial encryption of files above this threshold to improve the speed of encryption. Larger files will have smaller blocks of data encrypted throughout the file and a list of these blocks is saved in the metadata along with the key at the end of the file.

- Capability to scan for network shares in the local network.

- Persistence achieved via Startup folder and Run Registry key.

- Generation of target list of extensions and folders to encrypt.

- Process watchdog thread to kill processes that may hold target files open. This is done to improve the chances the important files will be encrypted.

- Disable system recovery, backup and shadow copies and the Windows firewall.

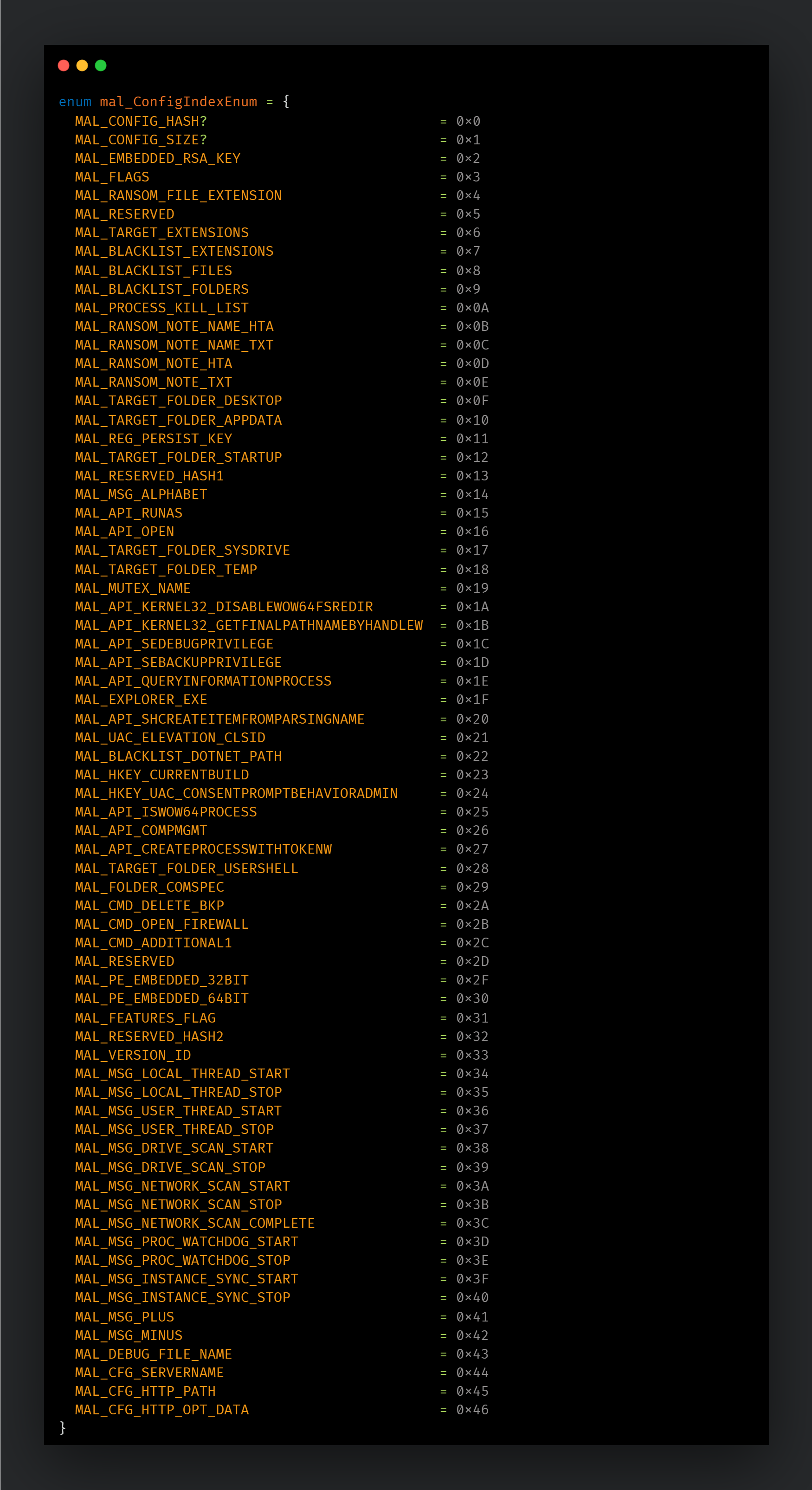

- Embedded configuration with more than 70 options available. This configuration is encrypted with the same AES function used to encrypt files, but using a hardcoded key.

Based on the analysis of this configuration data, we were able to uncover additional features present in the malware binary which can be enabled by setting specific options. These features have not been documented or have only been superficially mentioned in open source reporting to date:

- UAC bypass using a .NET profiler DLL loading vulnerability.

- The existence of a debugging file that enables additional features in the malware, illustrated in the following section.

- List of blocklisted file extensions that point to names of other groups using the Phobos malware.

- Dynamically imported API calls to avoid behavioral detection by security products.

- A hardcoded RSA key used to protect the per-file AES key used in the encryption.

- Reporting of victim infection to an external URL.

- OS check for Cyrillic language to prevent the malware from running in unwanted environments.

We also examined the encryption methodology used by Phobos. Versions of Phobos released after 2019 use a custom implementation of AES-256 encryption, with a different random symmetric key used for each encrypted file, instead of using the Windows Crypto API like earlier variants. Once each file is encrypted, the key used in the encryption along with additional metadata is then encrypted using RSA-1024 with a hardcoded public key, and saved to the end of the file. This algorithm has been documented before, for example in this Malwarebytes post from 2019, and the process still remains the same.

This makes it extremely unlikely the files can be decrypted by brute force, as each file uses a different key, even though attempts at brute-forcing it have been made in the past. It implies, however, that once the private RSA key is known, any file encrypted by any Phobos variant since 2019 can reliably be decrypted. This fact is supported by an analysis of over a thousand unpacked Phobos samples available on VirusTotal since 2019, where the same public RSA key mentioned above is used.

Next, we are going to take a deeper look at the configuration file and some of the features it enables.

Decrypting the Phobos configuration file

In order to understand how the configuration data is used in Phobos, we analyzed the malicious code in IDA Pro. This allowed us to interact with the configuration data using IDA Python and to decrypt all the configuration data at once. But first, we are going to look at how the configuration data looks in the binary. Once the file is loaded in IDA Pro, one of the first operations we observe being executed by the code is to check its payload and load it into memory:

In the code above we see the malware initially checking the CRC32 hash of the data in the last section of the PE file. In the case of our sample, this section is named “.cdata” although different samples may use a variation of this name. We have observed samples using “.cdata” and “.sdata”.

The data is then loaded into a heap-allocated memory and a structure with pointers to this data is saved to a global variable, named “payoad_struct_addr” in the image above. This structure will be used by the decryption function in order to load requested configuration entries later throughout the code. Each entry has a specific index which is passed as a parameter to the decryption function as we can see in the last code block.

The structure used to handle the configuration data has 48 bytes and is defined as follows:

The headers and the actual data are loaded in different buffers allocated in heap memory and pointers to these buffers are saved in the structure, as well as the number of entries in the configuration. The data is followed by a 16-byte AES key used to decrypt the configuration. This key is hardcoded in the binary.

The header contains information to find the encrypted data for each index in the configuration. The structure has 12 bytes and is defined as follows:

The offset above is relative to the start of the encrypted data buffer starting at 0x00. The index also starts at 0x00 and each index is relatively static for the type of data it contains, which means that for a given index, every sample should have the same type of configuration data in them.

We have, however, observed that some samples show small changes in the content of their indexes. Since Phobos has been used by many groups in the past, these variations could indicate they are using a different builder or variant. In our analysis of the public samples available in VirusTotal, we found that around 88% of them have 64 configuration entries, while some have as little as 40 and as many as 72 entries.

Based on our code analysis, we were also able to infer the existence of three additional options used for setting the reporting URL and custom message to be sent back to the attacker. These options were not observed in any sample we analyzed, but the code to handle them is present in all samples. A better look at this feature is shown later in this blog.

The decryption function accepts two parameters: an index to the desired entry and a pointer to a buffer that’s used if the entry contains more than four bytes of data. Otherwise, the buffer parameter must be zero.

The code scans the header buffer for an entry matching the requested index. It then allocates enough memory to store the encrypted data and copies the data to that space, and calls the AES_Init function with the key present at “payload_struct_addr + 0x10”, which is hardcoded in the sample data section. The function AES_Decrypt is then called with the encrypted data and this AES object as a parameter.

Automating the configuration decryption with IDA Pro

Once the decryption algorithm is understood, it is easy to automate the decryption of every entry in the configuration and output the details to a file. IDA Pro allows the use of Python to automate tasks inside the application, and we decided to use the Flare-Emu Python module to emulate the malware’s AES routines instead of re-implementing the code in Python.

Since the decryption function requires only two parameters and is therefore fairly independent, we decided to start the emulation from that point, creating a structure similar to what the malware does for the payload data:

eh=flare_emu.EmuHelper()

conf_struct=eh.allocEmuMem(0x30)

header_data=eh.allocEmuMem(header_size)

config_data=eh.allocEmuMem(config_size)

Then populating this structure with the appropriate values:

# load bufferseh.writeEmuPtr(conf_struct,header_data)

eh.writeEmuPtr(conf_struct+4,config_entries)

eh.writeEmuPtr(conf_struct+8,config_data)

eh.writeEmuPtr(conf_struct+0xc,config_size)

eh.writeEmuMem(conf_struct+0x10,AES_Init_key_struct)

eh.writeEmuMem(header_data,eh.getEmuBytes(enc_data_start+0x8, header_size))

eh.writeEmuMem(config_data,eh.getEmuBytes(config_start,config_size))

# write addr of struct back to code

eh.writeEmuPtr(eh.analysisHelper.getNameAddr(CFG_STRUCT_NAME), conf_struct)

Once the structure is created, we can walk through each entry in the header and prepare the emulator stack and call the emulation starting at the decryption function:

if entry_size<=4:

buffer=0

else:

buffer=eh.allocEmuMem(entry_enc_size)

myStack = [0xffffffff, entry_idx, buffer]

eh.emulateRange(eh.analysisHelper.getNameAddr(DECRYPT_FN), stack = myStack, skipCalls=False)

The resulting decrypted data will be present in the EAX register if it’s four bytes or less, or in the allocated buffer if larger. After our analysis of the samples found in the wild, we found the following types of configuration entries:

UAC bypass technique

To execute its main objective of encrypting as many files from the victim machine as possible, a ransomware needs to be executed with elevated privileges so it can access all files on disk as well as disable important system services which may hinder its objective. Elevating process privileges usually causes a warning to be displayed to the user and may prevent the malware from running. To bypass that message, many malicious programs use an UAC bypass or exploits to elevate its own process privileges.

The Phobos binary contains code that performs UAC bypass using a vulnerability in the .Net Profiler DLL loading process while executing “compmgmt.msc”. This technique has been documented since at least 2017 but still works in the latest version of Windows 10.

Note: Even though the malware contains code to bypass UAC and the exploit works when executed, this only happens once we force the execution to follow that specific code branch and is not being actively used by the malware. The code path leading to this specific function seems to be reachable only when specific parameters are present in the malware configuration. Since Phobos is generally distributed along other malware and only after the actors are able to extract all the information they need, it’s possible the UAC code is not used because it’s not needed at the point in time the actors decide to encrypt the files.

In this method, a DLL is dropped to a user-writable folder and the environment variables are modified to make the .Net profiler load the file even in elevated processes. In the case of Phobos, the configuration file stores a small 2KB DLL file that only contains code to create a new process with the malicious binary. Both 32- and 64-bit files are embedded in the configuration.

The DLL is written to the %TEMP% folder using the machine serial number as its name like this: C:\Users\User\AppData\Local\Temp\1E41F172.

The DLLs embedded in the configuration data do not represent a complete PE, containing only the data up to the import table present right after the “CALL [EAX]” shown above. The PE file is extracted from the configuration and fixed in memory before it is written to disk. The path to the malware binary is written to the file right after the import table, and will be used by the code as one of the parameters to “CreateProcessW”. The section is then finalized until the section alignment with the bytes 0xBAADF00D:

The code will then call ShCreateItemFromParsingName using “Elevation:Administrator!new:{3ad05575-8857-4850-9277-11b85bdb8e09}” as a parameter in order to create an elevated shell object which will later be used to initialize the .Net environment before executing the Computer Management tool via mmc.exe.

Once the exploit is successful, a new instance of the malware binary is started with high privileges:

The process tree is also worth noting, as it is not typical to have MMC.EXE starting unknown binaries, as shown in the example below:

Phobos’ hidden debug file feature

One of Phobos’ hidden abilities we found in the configuration data is support for a debug file which can be used to enable additional features in the binary. At the beginning of the code, Phobos checks for the presence of a file name at index 0x43 in the configuration. If the setting is present, it will then check if the file exists in the same folder and if it contains valid arguments:

If the debug file exists, Phobos will parse each line to see if they contain valid commands and will create a structure containing the flags and string parameters found after the commands. In the 8Base campaign, the name of this file is “suppo” but other groups use different names for the debug file or don’t have one set up at all.

Based on our code analysis, the following commands are available for debugging:

- ‘C’ or ‘c’: Shows a console to print debug strings.

- ‘L’: Outputs a log file name. This name will be prefixed by "e-" to indicate the process is running elevated. For a typical process tree with a low privilege malware running an elevated process, two files will be created: “filename” and “e-filename”.

- ‘M’ or ‘m’: Does not run the encryption loop. This option disables the malicious actions and causes the malware to jump to the end of the code.

- ‘n’: Sets a flag in the buffer.

- ‘e’: Accepts a string of values separated by ';' and stores a pointer to the data in the buffer structure.

- ‘s’: Sets a flag in the buffer.

- ‘x’: Sets a flag in the buffer.

While some of these commands can be derived from analysis of the code, Talos never found an actual sample of these debug files to compare with our analysis, so some of the commands are not yet completely understood.

When the options for showing the console are present in the debug file, this is what is output by the malware during typical execution:

In the example above, we have enabled the Console display (command ‘c’) and log file (command ‘L’) and we can see the messages printed to the console. It shows the victim identification (the string “[1E41F172-3483]”) as well as the build number “v2.9.1”. All the strings shown in the output are also present as settings in the configuration, which indicates these messages can be customized by the threat actors behind each campaign.

Phobos’ infection reporting capabilities

While Phobos does not typically demonstrate reporting a new infection to the attacker, our analysis indicates the capability to do so is present in the code, hidden behind a configuration setting which enables this feature and the creation of a custom URL and message chosen by the attacker.

The configuration setting with index “0x31” is a flag used throughout the code to check if various features are enabled or not. If the reporting capability is enabled, the malware will attempt to extract the server name, URI path and custom message from indexes 0x44, 0x45 and 0x46 respectively:

If these options are present, the malware will then attempt to communicate an alert of the infection back to the specified server. The custom message mentioned above is a string parameter which may contain the tag “<<ID>>” in its body. This tag will then be replaced by the victim ID before submitting the request. As shown in the example below, the original message extracted from the binary still has the tag and the parsed message with the victim ID is passed as parameter to the HTTP Post function:

The request is sent with almost no headers, as seen in this example:

It is worth noting, however, Talos has not seen any threat actor use this feature in any sample analyzed thus far.

Since 8Base group is known to operate with characteristics similar to previous Phobos campaigns, we compared the code in an 8Base sample with previous Phobos variants and determined there are no differences between the code at the binary level at all. As we mentioned above, this 8Base sample, 32a674b59c3f9a45efde48368b4de7e0e76c19e06b2f18afb6638d1a080b2eb3, was extracted from a SmokeLoader binary deployed in a recent 8Base campaign seen between June and August 2023.

In their February 2023 post about brute-forcing Phobos encryption, the Computer Emergency Response Team from Poland (Cert-PL) looked at sample 2704e269fb5cf9a02070a0ea07d82dc9d87f2cb95e60cb71d6c6d38b01869f66 which was first observed in VirusTotal in 2020. Their observations about how the encryption works had many similarities with the 8Base sample we analyzed, and our analysis revealed that there were no changes in the code at all, with 100% carryover of samples’ functions and basic blocks.

The only thing that changes between these two binaries is the configuration data in the last PE section:

8Base | Phobos Cert PL | |

Configuration Entries | 64 | 64 |

Encryption key | 0xea73000e61c749e5287a2407e44c8679 | 0x591abb0fe93e56e0d8c8fd2d6019f995 |

File extension (IDX 0x4) | .id[< | .id[< |

Debug file (IDX 0x43) | suppo | egvtethyr576.txt |

Extension Blocklist (IDX 0x7) | 8base;actin;DIKE;Acton;actor;Acuff;FILE;Acuna;fullz;MMXXII;6y8dghklp;SHTORM;NURRI;GHOST;FF6OM6;MNX;BACKJOHN;OWN;FS23;2QZ3;top;blackrock;CHCRBO;G-STARS;faust;unknown;STEEL;worry;WIN;duck;fopra;unique;acute;adage;make;Adair;MLF;magic;Adame;banhu;banjo;Banks;Banta;Barak;Caleb;Cales;Caley;calix;Calle;Calum;Calvo;deuce;Dever;devil;Devoe;Devon;Devos;dewar;eight;eject;eking;Elbie;elbow;elder;phobos;help;blend;bqux;com;mamba;KARLOS;DDoS;phoenix;PLUT;karma;bbc;CAPITAL;WALLET;LKS;tech;s1g2n3a4l;MURK;makop;ebaka;jook;LOGAN;FIASKO;GUCCI;decrypt;OOH;Non;grt;LIZARD;FLSCRYPT;SDK;2023;vhdv | Barak;actin;Acton;actor;Acuff;Acuna;acute;adage;Adair;Adame;banhu;banjo;Banks;Banta;Barak;Caleb;Cales;Caley;calix;Calle;Calum;Calvo;deuce;Dever;devil;Devoe;Devon;Devos;dewar;eight;eject;eking;Elbie;elbow;elder;phobos;help;blend;bqux;com;mamba;KARLOS;DDoS;phoenix;PLUT;karma;bbc;CAPITAL;WALLET; |

The same holds true for other samples found since 2020. The differences in code start to appear when we compare the 8Base sample with Phobos variants created in 2019. We analyzed the sample fc4b14250db7f66107820ecc56026e6be3e8e0eb2d428719156cf1c53ae139c6 first seen in VirusTotal in August 2019. The current 8Base sample shares 89.6% of its code with the 2019 sample, according to our analysis.

There are several functions present in the current 8Base sample that did not exist in 2019:

There is now support for debug files and infection report capabilities, which are not present in the old samples. This implies these features were added to Phobos source code at some point in 2019 or 2020, likely the last time the Phobos source code was updated.

Another sample that caught our attention was first described by Malwarebytes in 2019. The sample, a91491f45b851a07f91ba5a200967921bf796d38677786de51a4a8fe5ddeafd2, was first observed in the wild in May 2019. This sample is considerably different from other samples from the same time frame, only sharing 47.2% of their code.

The main difference we observed in this sample is the usage of Windows Crypto API instead of the custom cryptographic code from recent samples. Looking at the functions present in the 2019 sample, we can see the Crypto API imported by this sample:

We observed these APIs being used in some critical functions throughout the code. The code block below is related to the encryption/decryption function in 8Base, which uses the custom cryptographic library, versus the code in the 2019 sample which uses Windows Crypto API

There are similar differences in the function used to decrypt the configuration file, which behaves in a related fashion but using different cryptographic APIs.

These changes observed in early samples support the assumption that Phobos went through a development phase in 2019 but has remained unchanged since then.

In our second post titled "Understanding the Phobos affiliate structure and activity ", we will have additional information on the data we found in the blocklist extensions and how this is mapped to different actor groups, as well as the behavior of such groups once they get into a victim’s network.

Cisco Secure Endpoint (formerly AMP for Endpoints) is ideally suited to prevent the execution of the malware detailed in this post. Try Secure Endpoint for free here.

Cisco Secure Web Appliance web scanning prevents access to malicious websites and detects malware used in these attacks.

Cisco Secure Email (formerly Cisco Email Security) can block malicious emails sent by threat actors as part of their campaign. You can try Secure Email for free here.

Cisco Secure Firewall (formerly Next-Generation Firewall and Firepower NGFW) appliances such as Threat Defense Virtual, Adaptive Security Appliance and Meraki MX can detect malicious activity associated with this threat.

Cisco Secure Malware Analytics (Threat Grid) identifies malicious binaries and builds protection into all Cisco Secure products.

Umbrella, Cisco's secure internet gateway (SIG), blocks users from connecting to malicious domains, IPs, and URLs, whether users are on or off the corporate network. Sign up for a free trial of Umbrella here.

Cisco Secure Web Appliance (formerly Web Security Appliance) automatically blocks potentially dangerous sites and tests suspicious sites before users access them.

Additional protections with context to your specific environment and threat data are available from the Firewall Management Center.

Cisco Duo provides multi-factor authentication for users to ensure only those authorized are accessing your network.

ClamAV detections are available for this threat:

Win.Packed.Zusy

Win.Ransomware.8base

Win.Downloader.Generic

Win.Ransomware.Ulise

Indicators of Compromise associated with this threat can be found here.