2024-1-10 21:16:19 Author: therecord.media(查看原文) 阅读量:11 收藏

For nation-state actors targeting adversaries in cyberspace, unpatched vulnerabilities in software are like ammunition. As a general matter, intelligence agencies and military hackers spend millions of dollars in the gray market and thousands of man-hours in a bid to dig up flaws in code that no one has discovered yet.

But for the past two years, China has short-circuited that process. It passed a law in 2021 that requires any business operating in China to report any coding flaws to a government agency before patching the vulnerability or revealing its existence publicly. A report from the Atlantic Council makes clear that the information about the bug is then shared with China’s state-sponsored hackers, who proceed to exploit them.

Click Here spoke with one of the authors of the report, Dakota Cary, about China’s vulnerability disclosure process and how the law is part of a broad plan to reinvigorate China’s pipeline of cyber talent.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

CLICK HERE: China has a singular approach to software vulnerability reporting. How is it different from the U.S. system?

DAKOTA CARY: I have a colleague who worked for the U.S. government, and he was on a trip overseas to China. He was talking with somebody in the Chinese military about how it seems like many institutions that are seemingly unaffiliated with the military do work on behalf of the security services. Everyone seems to have their fingers in everyone else's pot. And she said, “That's because you, as an American, are quite legalistic.” She takes a piece of paper and she draws a box on it and draws a line through the box. And she says, “Americans are like this. Your stuff is over here, and somebody else's stuff is over here, and stuff outside this box is stuff that you don't touch.” And then she drew the yin and the yang sign on it, and she said, “China is more like this, where we know what we're meant to do. And we're all working towards those goals, regardless of where our respective authorities are.”

And so you see a lot of collaboration and competition in China, where agencies are trying to do the same work better than their political competitors and other bureaucracies. And so you see that in the actual structure of vulnerability databases, where previously it was voluntary disclosure to China's critical incident response center or the intelligence services. Now you have to disclose it under penalty to the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. And when we look through the lists of companies that are participating in the Ministry of Industry of Information Technology database, there's incredible overlap between companies who service the intelligence services and the military, as well as actual military and intelligence institutions that are participating in these databases. The system does not prize efficiency. The system prizes results. That's the context in which this law is being implemented.

CH: If we were trying to think of this vulnerability disclosure law in the context of the U.S., would it be like finding vulnerabilities and forwarding them to the NSA?

DC: It's a good question. It is effectively like we told all of the companies and researchers in the United States that they had to disclose software vulnerabilities to CISA. And then we told the CIA and the NSA to go partner with CISA on that vulnerability database. And that's why the title of the paper is “Sleight of hand,” because [the law] does not clearly state, Please hand this to the intelligence services. It says, Please hand it to this intermediate organization whose membership includes the military and intelligence services. It's quite the handoff.

CH: You obtained a copy of the form that researchers have to submit to the Chinese authorities. What do they have to reveal?

DC: Right, what we effectively have is their input form. You find the vulnerability and you're submitting it. What information do they ask for? They ask if it's already public, if somebody else knows about this, if there are URL links to other information about this, if somebody's talked about it before, the name of the product, the manufacturer, the software type. And then it asks, like, really detailed questions about it — please specifically indicate how to trigger the software vulnerability. And they even have sections on the website where you can upload your own proof of concept code. China doesn't want that posted [publicly] because it helps script kiddies or offensive hackers who do ransomware attacks and stuff like that. But if you happen to have written a proof of concept code, you can submit it to the government if you so choose. And so you can upload a file and effectively help them create a tool to exploit that vulnerability.

CH: And you ended up with a copy of the form how?

DC: So that, uh, I think it's pronounced “sources and methods,” if I'm not mistaken [laughter].

CH: What did vulnerability disclosures look like in China before 2021?

DC: Before the 2021 law goes into effect, companies or researchers are individually choosing to participate and voluntarily telling one of two government agencies about a software vulnerability. Prior to 2017, Chinese researchers were permitted to participate in foreign competitions. So they would come to the United States and they would do really well at software security competitions like Pwn2Own and things like that. And then in 2017, the government and the Ministry of Public Security passed regulations stating that vulnerability researchers could not leave China to participate in these competitions. They effectively were saying, You can’t disclose these vulnerabilities overseas for cash. At the same time, they set up their own competition inside China called Tianfu Cup. And it comes along right at the time when researchers are no longer allowed to go abroad for these things. It also pays them cash, and it's the recreation of a typical software security competition. Reporting by the MIT Technology Review in 2021 showed that a vulnerability from that competition was picked up by the Chinese government within a day and then used to target Uyghurs in Xinjiang. And so it is a very easy throughline between this competition and Chinese government capabilities.

CH: The Tianfu Cup was also about building talent, right?

DC: Yeah, absolutely. Not only is it trying to replace foreign competitions for Chinese researchers. It's also trying to promote the talent pipeline. At this point, [China had] revamped its education system for cybersecurity. It put a bunch of new certifications in place. It structured a new collegiate curriculum for cybersecurity, and they're trying to get the youth of China — K-12 students — interested in a career in cybersecurity. So this other motivation, besides just software vulnerabilities, is that having these hacking competitions in China is a good way to promote students' interest in this as a career field.

CH: At that point, though, Chinese white hat hackers could still openly find and report vulnerabilities to international companies, right?

DC: Yes, even from 2017 to 2021, Chinese researchers were participating in the global ecosystem for software security. They were selling or providing information on software vulnerabilities through bug bounty programs to global companies like Microsoft, Tesla, Apple, Oracle, you go down the list. Many of them have these programs where they say, if you can find a software vulnerability in our code that is so severe that X, Y, and Z, then we'll pay you money to tell us about that vulnerability. You won’t tell anyone else. We will verify it. We'll fix it, and then you'll get the money afterwards.

All of that was good and well under the Chinese system, even though they weren't allowed to go abroad after 2017 for those competitions. Then in 2021, the Chinese government effectively sits itself on top of that pipeline by putting these regulations in place where [researchers] have to disclose those vulnerabilities to the Chinese government. Whether you're a firm operating in China or you're a researcher who finds that vulnerability, they effectively put a gag rule in place saying you can't talk about it unless you tell the government and there is a patch issued by the company. You can't hype up the severity of it, and you can't publish proof of concept code. And instead of the Chinese government having to go into the market to find and purchase those vulnerabilities, they are siphoning off the value of that marketplace for free.

CH: In your research, did you come upon white hat hackers who had left China because of these regulations? Is there any pushback from the security researcher industry?

DC: It's really hard to talk about this without risking the safety of people who are in China. I don't have a direct relationship [with any Chinese researchers], but I've seen indications that some people at least understand and know that the system they're participating in does support the government in some capacity. I think that's effectively as much as I can say on that topic.

CH: To what extent are non-Chinese companies complying with these regulations?

DC: So the report that I co-authored with Kristin Del Rosso mentions having spoken with a non-Chinese company that was participating in the system. And that was the decision of a local branch of the company to comply with Chinese law. I've made this point to audiences, but the degree to which foreign firms comply with these regulations is very much subject to their own interpretation of the law and the risks that they're willing to take. For example, I claim no particular insights into the way Microsoft makes decisions. But Microsoft is such a globally important company that I would be astounded if they were participating in this new system without having figured out some sort of workaround — either to provide as little information as possible or to plead ignorance of a particular vulnerability and just patch it anyways, and then talk about it later.

Microsoft, Apple — these companies are so big and important to both the Chinese economy and global economy that Chinese regulators are not really in a position to force those firms to behave in that way. That's my personal opinion. I don't know what actions those companies are taking, but I don't think it's as black and white as the regulations might convince us to believe.

CH: There’s one thing I’m trying to square here. Your report includes a quote: “Software vulnerabilities are like raspberries—they go bad fast.” At the same time, there's also this concern that China’s offensive hackers are holding onto these vulnerabilities for later use. Would those vulnerabilities still even be helpful weeks, months, years later?

DC: Yeah, the majority of software vulnerabilities associated with companies do change quickly. And as fast as there's an update for that software, the landscape changes and intelligence services or militaries risk losing access. So having a pipeline of these [vulnerabilities] enables operational tempo. You can imagine a team of people sitting down for work that day and they go, OK, we have to get into company A. What do we know about company A's system? And they look at their reconnaissance inventory and they [say], They're running this system, and they're running that system. They pull up their database of vulnerabilities and they go, OK, what do we have that matches into these targeted systems that we can utilize?

And as long as those version numbers line up between the vulnerability and whatever that company currently uses, then that's something they can use in their operation. It allows them to act more quickly in those operations rather than having to sit around and wait for somebody to go develop a vulnerability, which can months or longer — and lots and lots of cash.

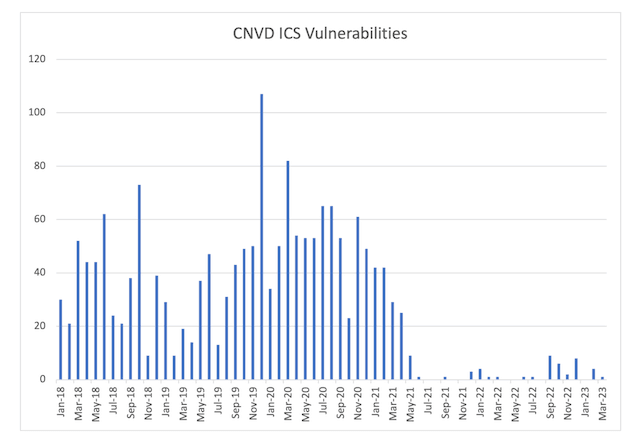

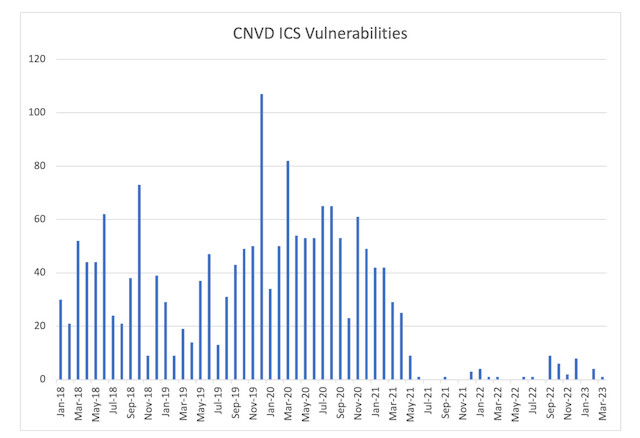

CH: Going back to the number of vulnerabilities reported, it’s night and day when you compare pre-2021 to post-2021. Are there any data points that you found particularly illuminating?

DC: Yeah, so we looked at the vulnerability data from a voluntary reporting platform, which was under [CNCERT]. This is one of the original voluntary reporting databases. And the data for the industrial control systems, from 2018 up until 2021, was consistently over a hundred software vulnerabilities being reported out by that agency made public each year. So people who either operate those systems or people who use those systems would be able to read that information, know that there's a software vulnerability and, if a patch is available, apply that patch.

Then, the data shows a dramatic cut off to almost no vulnerabilities being disclosed by that database for industrial control systems in the summer and fall of 2021. So you can imagine this chart, it's got big bars all the way up and down — month after month, year after year. And then 2021, it just hits the bottom and almost flatlines, right? The patient has died. There are no more software vulnerabilities coming out of this database. And it's telling because we know that researchers in China are able to find industrial control system software vulnerabilities with regularity on the order of at least 100 a year. And now the public data shows that between six and 10 are being released every year. The dramatic drop off in that data suggests that even though these people are still producing software vulnerabilities, the companies who are responsible for patching and updating their software are not issuing patches. And so the question is, do they know that their products are vulnerable? Are they being told that their products are vulnerable so that they can patch them? Or are those companies not receiving intelligence from this new system? Are those researchers still finding software vulnerabilities in industrial control systems and not telling the companies responsible for those products?

SOURCE: “Sleight of hand,” Dakota Cary and Kristin Del Rosso

SOURCE: “Sleight of hand,” Dakota Cary and Kristin Del Rosso

CH: The Tianfu Cup, the educational system, the databases, the 2021 regulations. Do you see these as all part of a continuum?

DC: Absolutely. In the intro of the paper we talk about this [Chinese] attitude — that software vulnerabilities are like this natural resource, this imbued endowment to the Chinese government and the Chinese people. There's a quote in there that compares [software vulnerabilities] to, like, timber and coal. That’s their language. They're very much [saying], This is a thing that belongs to us and it should not go overseas.

Get more insights with the

Recorded Future

Intelligence Cloud.

No previous article

No new articles

Dina Temple-Raston is the host and executive producer of the Click Here podcast as well as a senior correspondent at Recorded Future News. She previously served on NPR’s Investigations team focusing on breaking news stories and national security, technology, and social justice and hosted and created the award-winning Audible Podcast “What Were You Thinking.”

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh