2024-1-30 22:46:17 Author: therecord.media(查看原文) 阅读量:14 收藏

New Jersey’s governor signed a hard-fought data privacy law earlier this month, making the state one of eight nationwide to enact comprehensive privacy legislation in the past year. Getting there wasn’t easy, though, says the legislator who was the driving force behind the bill.

State Sen. Raj Mukherji says the technology industry’s effort against the legislation was staggering in its scope and intensity.

Mukherji, a Democrat, said he crafted his own bill, but the industry pushed a weaker model of legislation — a 2022 law passed in Connecticut — as a template. The senator said he resisted those efforts, and the New Jersey bill is now seen as one of the country’s toughest, including enhanced privacy provisions that go beyond what many other states have achieved.

The industry’s effort to weaken the bill bordered on parody, he said.

“Some folks were actually calling me saying they were opposed to the bill, but they weren’t sure why, and their clients weren’t sure why,” he said via email.

Ultimately he said he had to fend off “eleventh hour copy-and-paste, inartful opposition from dozens of industry lobbyists, echoing the same points (in many cases verbatim) about the Attorney General’s rule-making authority, our universal opt-out mechanism, partial opt-in for sensitive data and revisions we made to our private right of action language.”

All of those provisions in the law allow individuals more control over how companies handle their data and give regulators more power to protect consumers from having their information shared with third parties, such as data brokers.

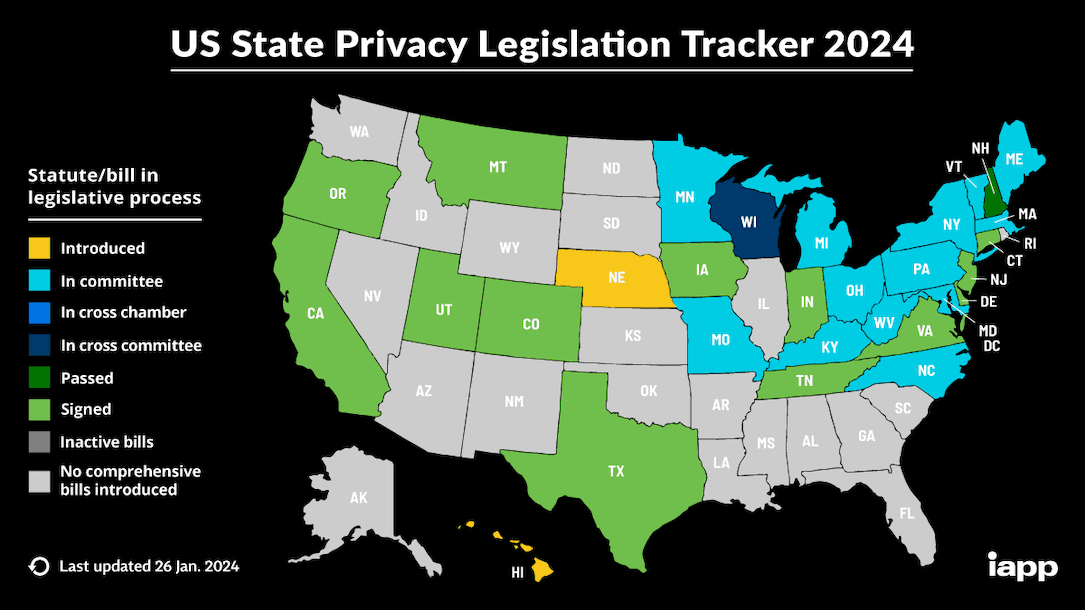

Privacy advocates say the process in New Jersey is just one more example of how the industry — including the biggest names in Silicon Valley — has sought to water down such state legislation through an intense and highly organized campaign. Thirteen states now have privacy laws on the books, and bills are currently being negotiated in more than a dozen more, but in many of those states, industry has successfully undercut significant aspects of the legislation or is attempting to, experts and legislators say.

Source: International Association of Privacy Professionals

Source: International Association of Privacy Professionals

Tech companies want bills that do not include a private right of action, such as personal lawsuits; do not include strong data minimization language, which limits how much information companies can keep on hand; do not let consumers opt-in to data protections in most cases; and feature narrow definitions for what qualifies as a data sale, among other things. The tech industry’s argument is that extensive data protections stifle innovation and are hard to comply with, particularly when rules differ from state to state.

TechNet, a trade association that lists Apple, Comcast, Google, Meta and Salesforce among its many members, wrote several New Jersey legislators an aggressive appeal to delay the Mukherji bill because it had been amended to include what the association called a “threat of litigation for private rights of action” as well as as language allowing consumers to opt in to targeted advertising, giving people more power to avoid having their data sold for commercial purposes. The email, obtained by Recorded Future News, also said the bill would be disruptive in creating “broad authority” for the state Office of the Attorney General to set rules governing the universal opt-out mechanism.

With federal privacy legislation stalled, tech companies are pushing to implement a large number of favorable state laws to kill momentum for Congress to act while still attempting to set a national standard, advocates say.

David Edmonson, TechNet's senior vice president of state policy and government relations, said in a statement that the growing patchwork of state laws is “confusing consumers and having a chilling effect on our economy.” For that reason, he said, TechNet has been actively lobbying lawmakers across the country on privacy legislation to “promote interoperability and consistency from state to state.”

NetChoice, a trade association representing tech companies, also has been pushing a national standard, according to a statement from Carl Szabo, NetChoice vice president and general counsel.

“Part of the problem with the wide variety of state laws on the books is that it is incredibly hard for small businesses to afford compliance with many different and sometimes conflicting laws,” Szabo said. “NetChoice will continue to fight to ensure free enterprise and free expression online.”

The cut-and-paste approach

Privacy advocates working to push bills as strong or stronger than New Jersey’s have been demoralized by the tech industry’s well-funded efforts. Many worry that with a quickly expanding number of states adopting industry-shaped legislation — Virginia’s law, partially written by Amazon, has been a favorite model — momentum for federal action will slow even more than it already has and weaker laws will be difficult to overturn later.

The main models in play for the tech lobby are Connecticut and Delaware, which it shops to blue states; and Utah and Virginia, which are promoted to red states, advocates and legislators say. Utah’s law is even more industry-friendly than Virginia’s tech lobby-shaped approach.

The Delaware and Connecticut laws are similar, experts said, but are notably weak for blue-state norms. Delaware passed its bill in September. Compared to Connecticut’s, it contains a more restrictive exception for publicly available data and a broader right to delete data. It also includes protections for sensitive personal data such as gender identity and pregnancy status, experts say.

Connecticut’s bill is also similar to Virginia’s, but the tech lobby has successfully used Connecticut’s reputation as a liberal Northeastern state to push that model in other states with similar politics, according to R.J. Cross, the director of the Don't Sell My Data Campaign at PIRG, a nonprofit advocacy group.

“You see that template bill taken and pushed in the name of ‘make this easy for companies to comply with,’” Cross said. “The Connecticut model and the Virginia model are not fundamentally that different, but they sound different enough and it is that familiarity of ‘OK, what passes in Connecticut may work for my state’ if you’re Maine or Massachusetts.”

Utah’s bill is even weaker than Virginia’s, advocates say. It doesn’t give individuals the ability to fix incorrect personal data or the right to opt out of “significant profiling decisions,” according to Keir Lamont, director for U.S. legislation at the Future of Privacy Forum. It also doesn't mandate that businesses get “opt-in consent” to handle sensitive personal data and does not include typical data minimization provisions and “limitations on secondary uses of data,” Lamont said.

The modeling technique is not an unprecedented strategy. For example, the American Legislative Exchange Council, an organization for state legislators seeking limited government and free markets, uses a similar method and even maintains a “model policy library” for legislators to consult. Model legislation can come from government agencies, too, like gun safety bills proposed by the U.S. Department of Justice in 2023.

The model approach is succeeding for the tech lobby in creating a “false sense of consensus around weak bills to lock in a de facto national standard that requires consumers to chase after data brokers with no meaningful legal recourse,” said Cody Venzke, senior policy counsel at the ACLU.

Democratic Maryland Del. Sara Love has been working on a comprehensive state privacy bill since last year. Love said she began with the Delaware template but changed several provisions to strengthen privacy protections. Tech lobbyists pushed back.

“They want a straight-up Delaware model — they don't want any changes,” Love said in an interview. “The argument is ‘as long as we have something consistent, that is easier for our business model.’”

At first that claim made sense to her, Love said. But then she said she began thinking about how companies manage to tweak compliance to adhere to transatlantic rules. As she spoke to tech lobbyists it became increasingly clear to her that the argument was an excuse for keeping language weak, she said.

Her bill was introduced January 24.

Feeling deceived

Montana, a red state, enacted a relatively strong bill in May because Republican State Sen. Daniel Zolnikov resisted industry efforts to impose the Utah model, he said.

“I wanted Connecticut,” said Zolnikov, who discussed his experience with Politico in June. “They [tech companies] said fine and then attempted to water it down.”

Zolnikov said he was open to using another state’s provisions because the technical nature of the issues makes it easier to work from a template. But he was put off by how industry tried to push him to draft a weaker bill, presumably because Montana is a red state.

“I gave them a chance and they treated me like an idiot,” said Zolnikov, who added that he worked with tech companies in “good faith” at the outset.

Then someone sent him Maryland testimony in which a tech lobbyist pushed the Connecticut bill without changes, saying companies would be completely supportive. But when Zolonikov embraced the Connecticut legislation, industry representatives rebelled, he said.

“How come in Maryland the Connecticut bill is good enough, but in Montana it's not and they wanted to fix it?” Zolnikov said. “That pissed me off.”

He called the tech lobby’s modeling campaign a “state-by-state effort to get the lowest common denominator concept through or to make sure that bills don't pass in the first place.”

Tech companies’ representatives tried to tell Zolnikov the universal opt-out mechanism is unproven and hard to comply with, he said. They urged him to tweak the bill to give companies the ability to change their practices “in perpetuity.” Zolnikov said he was told several times by industry that major tweaks were “just a really small thing.”

An army, always ready

New Hampshire sent its comprehensive privacy legislation to its governor on January 18. State Rep. Marjorie Smith, a Democrat who helped write a version of the bill that passed the state House of Representatives earlier this month, said she looked at other states’ legislation when drafting it, but, like Love, made changes.

She said the tech industry pushed New Hampshire to undertake a bill, using what she found to be a compelling argument.

“What has been presented to us is that since the federal government, the Congress, is not doing what it should do, what makes the most sense is to have as many states as possible pass legislation that is about the same,” Smith said, describing the tech lobby’s message.

But she said she believes New Hampshire’s bill was not weakened by tech companies despite their best efforts.

Tech industry representatives descended on the state, Smith said.

“We have been amused to see people somewhat near the top of some of the major organizations in the country flock to little New Hampshire,” Smith said. “We tend generally not to be overly impressed when a big national organization decides to send its people in Gucci loafers to New Hampshire to tell us what to do.”

Love, the Maryland legislator, said that what has been shocking to her is how many groups are representing the same tech companies under different names. NetChoice, TechNet and the State Privacy and Security Coalition (SPSC) are among the most common groups to show up in the state assemblies, along with lobbyists for individual companies, she said.

“Basically all the same groups are quadruple-dipping,” Love said. “So, while it may appear at first blush that there are four different groups maybe representing different companies, they're really all basically the same.”

Love said the tactic makes it seem like there is more widespread opposition to a given bill than is really the case.

The lobbyists also have taken advantage of the highly technical nature of the bills to cow middle-of-the-road legislators away from supporting tough provisions by taking advantage of their lack of technical prowess, Love said.

“They know more about the technicalities and the weeds of the process than the legislators with whom they are speaking so they can say enough things that sound concerning to make legislators think, ‘Oh, wow, there are big problems here and then back down,’” Love said.

‘State’ but not from the states

Legislators and privacy advocates tracking the state efforts said one group has particularly stood out for its success and omnipresence: the SPSC. The organization has testified in many states and is quoted in local newspapers across the country undermining legislation and doing so in easy-to-understand language.

Zolnikov bristled at how SPSC uses what he called a “misnomer” and “bullshit” to trick legislators into thinking it’s not on the tech lobby bandwagon. SPSC represents a variety of companies from different sectors, including telecommunications giants and credit card companies, but most of the major tech firms and associations are under its umbrella.

“Doesn't that sound like a coalition for states that want privacy?” Zolnikov said. “They're trying to sound good to legislators [who think] ‘those guys must be on our side.’ It's an easy assumption to make.”

SPSC has been around for well over a decade. Cross, of the Don't Sell My Data Campaign, said the coalition formed in 2008 shortly after Illinois passed its tough Biometric Information Privacy Act, which includes a private right of action allowing individuals to sue companies which they believe have violated the law.

“They show up everywhere,” Cross said. “One of the talking points they push strongly is that there can't be a private right of action.“

In fact, SPSC has succeeded in getting a private right of action removed “in just about” every state where it has lobbied, Cross said.

A lawyer for SPSC, Andrew Kingman, said in a statement that the organization believes consumers deserve “clear rights and regulations that improve transparency and protections for their data, regardless of the state in which they reside. Businesses require certainty to plan, innovate, and provide the services and products consumers need and expect.”

He added that SPSC is working with state policymakers, advocates and industry experts in the absence of federal legislation to “inform consistent regulatory principles that protect users’ data and privacy while ensuring a level playing field for businesses of all sizes.”

Cross said that response matches what SPSC is telling state legislators nationwide. .

“They have a really good story that they tell that all these industries are going to be impacted and it's important for regulators to all find one standard nationally that they can support so it's easier for these companies to follow these laws,” Cross said. “And so you just see that template bill taken and pushed in the name of ‘make this easy for companies to comply with.’”

Get more insights with the

Recorded Future

Intelligence Cloud.

No previous article

No new articles

Suzanne Smalley

Suzanne Smalley is a reporter covering privacy, disinformation and cybersecurity policy for The Record. She was previously a cybersecurity reporter at CyberScoop and Reuters. Earlier in her career Suzanne covered the Boston Police Department for the Boston Globe and two presidential campaign cycles for Newsweek. She lives in Washington with her husband and three children.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh