2024-2-12 19:0:25 Author: www.sentinelone.com(查看原文) 阅读量:14 收藏

Executive Summary

- China launched an offensive media strategy to push narratives around US hacking operations following a joint statement by the US, UK, and EU in July 2021 about China’s irresponsible behavior in cyberspace.

- Some PRC cybersecurity companies now coordinate report publication with government agencies and state media to amplify their impact.

- Allegations of US hacking operations by China lack crucial technical analysis to validate their claims. Until 2023, these reports recycled old, leaked US intelligence documents. After mid-2023, the PRC dropped pretense of technical validation and only released allegations in state media.

- The cyber-focused media campaign preceded the 2023 efforts of China’s Ministry of State Security to disclose accounts of western spying in the PRC.

Introduction

In the western media and cybersecurity industry in general, we have become familiar with regular reports of nation-state espionage activities often attributed to China or Chinese-linked threat groups. Such reports rest their credibility on the level of meticulous technical detail and evidence-based claims contained therein.

In contrast, claims of espionage and cyber intrusion attributed to western nation-state agencies emanating out of China’s Ministry of State Security and Chinese cybersecurity firms are notably lacking in the same kind of technical detail or evidential proof.

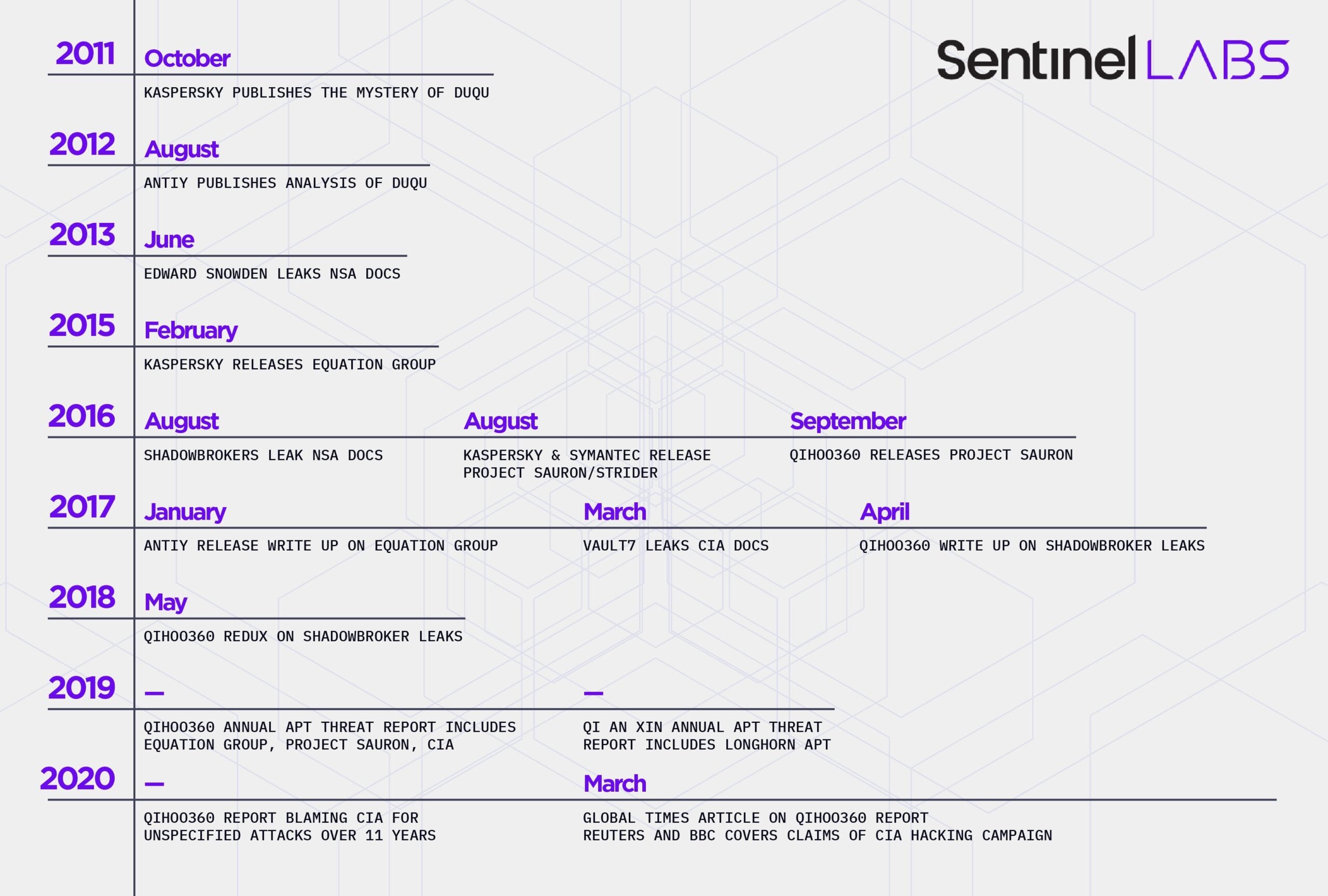

Between the first reports establishing US involvement in Stuxnet and the summer of 2021, China’s most prominent actors in the cybersecurity industry never independently established attribution of hacking inside the PRC to any US-affiliated APTs, nor did the analysis of US-nexus hacking extend beyond tools and exploits.

China’s cybersecurity companies also never published the underlying technical data that is considered table stakes for non-Chinese companies. The companies only regurgitated information from foreign vendors or leaked US intelligence documents. This was a matter of policy, not capability. Such reports were likely written and held back from external publication since at least 2016.

Below, we describe how and why this strategy came into play. Interested readers can find a more detailed analysis in the full report.

China Pivots to Rehashing Old Quarrels

In the winter of 2021, a PRC hacking team was taking advantage of four vulnerabilities in Microsoft Exchange Servers. When intelligence that Microsoft was planning to patch reached the team, they shared the vulnerability with others and automated their attack for scale.

This significant increase in abuse, in concert with its arbitrary targeting that left victims vulnerable to much easier compromise, pushed the U.S., U.K., and the EU jointly to issue a statement condemning China’s behavior in cyberspace. The joint statement so irked the PRC government that it began a media campaign to push narratives about US hacking operations in global media outlets.

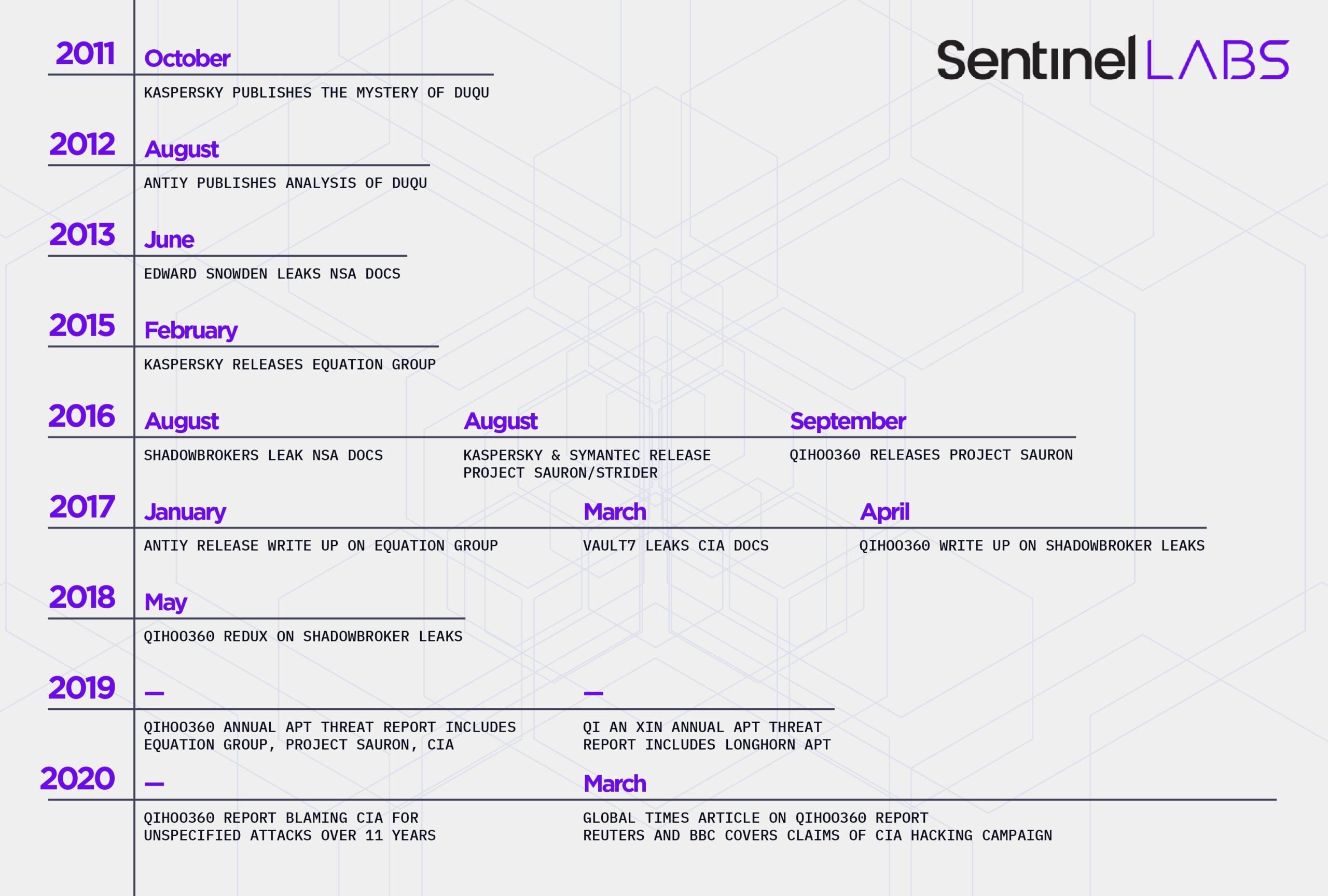

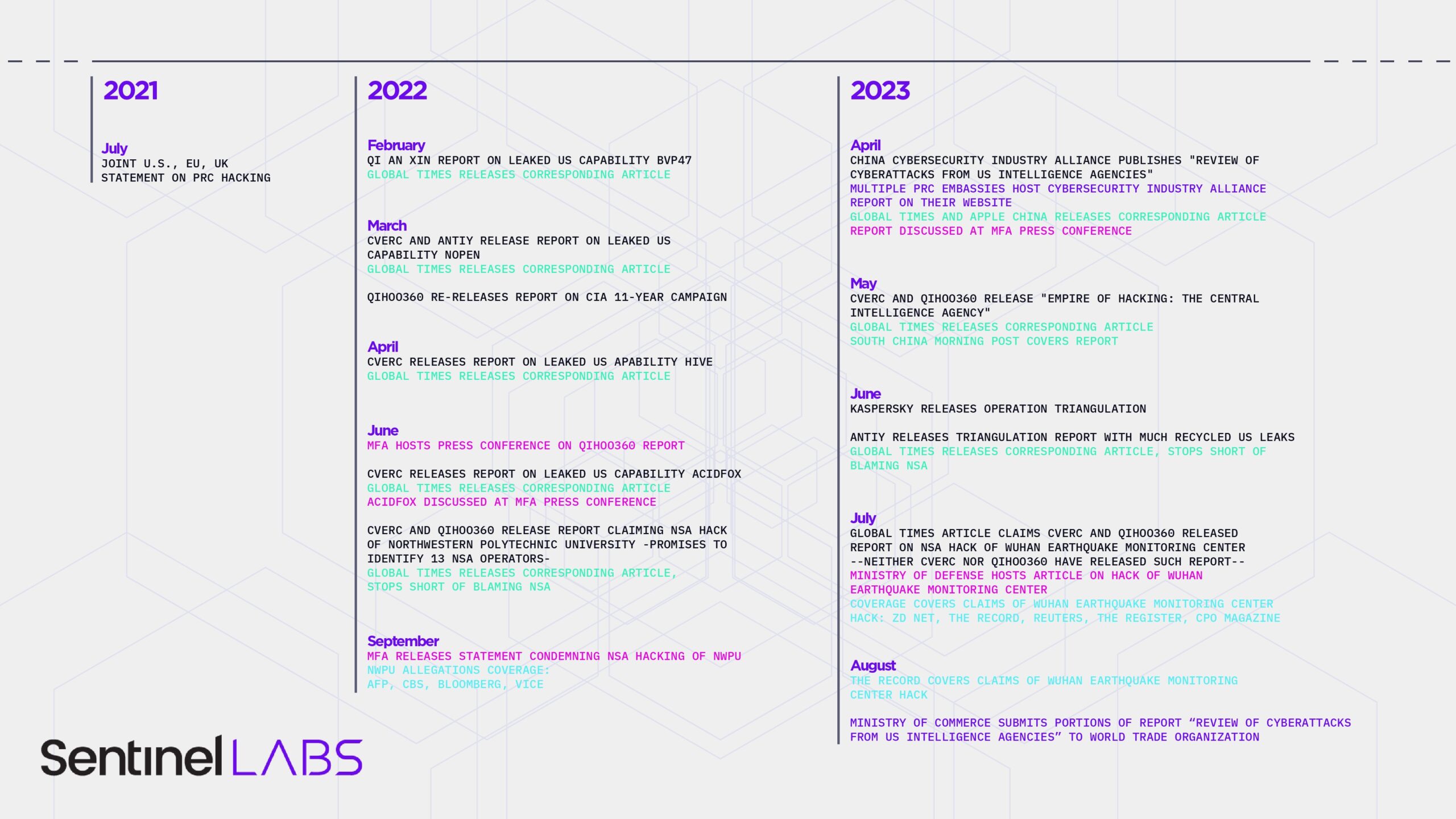

Starting in early 2022, state media began releasing English-language articles to accompany CTI publications by PRC cybersecurity companies and government agencies. This marked a shift in China’s approach to discussing foreign espionage, highlighting US hacking activities more frequently to a global audience.

In 2021, Global Times only mentioned the NSA twice–both in the context of railing against global capitalists. In 2022, the publication mentioned the NSA in connection to hackings tools or operations 24 times.

But the reports released throughout 2022 and into 2023 continued to draw from leaked US government documents, not new technical analysis by PRC companies. They were, in effect, recycling old content for propaganda purposes. The China Cybersecurity Industry Alliance released its Review of Cyberattacks from US Intelligence Agencies in 2023, summarizing over a decade of research on US cyberattacks, albeit without new evidence. Of the nearly 150 citations in the report, less than one-third are attributed to PRC vendors. A full accounting of these publications is available in the full report.

A New Era

In July 2023, China did something it hadn’t done before—it spread new allegations of US hacking apparently unrelated to past US intelligence leaks and, as of this report, entirely unsubstantiated.

In a series of publications by Global Times, the CEO of Antiy claimed the United States had hacked into seismic censors of the Wuhan Earthquake Monitoring Center. His claims, along with those of the Global Times, were ostensibly based on a report from CVERC and Qihoo360. But this report, if it exists, is not yet public. Neither CVERC nor Qihoo360 host such a report on their respective websites, nor does any PRC government agency. Qihoo360’s only mention of the Wuhan Center is a community board post by an anonymous user referencing state media.

The lack of technical details–or in this case, a report at all–did not stop the story from getting attention. A handful of cybersecurity industry outlets in the U.S. picked up the story and ran it in July and August after the Global Times published another report covering the allegations. This time, state media claimed that “Chinese authorities will publicly disclose a highly secretive global reconnaissance system of the US government…” To date, this remains yet another report that has not been released.

The allegations of US hacking without technical evidence coincided with China’s Ministry of State Security launching its public WeChat account. Since the middle of 2023, the MSS has published four accounts of foreign spies operating in China and being caught. Three are alleged to have been working for the U.S., a fourth was alleged to have worked for the UK and was tied to office raids of foreign due diligence firms. Off-the-record American officials confirmed one of the US cases to press later in the year. Further discussion of China’s allegations of human intelligence collection is available in the full report.

Conclusion

China has not yet published detailed accounts that analysts have come to expect from cybersecurity firms. Accepting this asymmetry in data sharing benefits China, allowing the country to publish claims of foreign hacking without the requisite information. If analysts do not actively challenge the CCP’s claims, the government can lie with impunity.

Repeating China’s allegations helps the PRC shape global public opinion of the U.S. China wants to see the world recognize the U.S. as the “empire of hacking.” But outright ignoring China’s claims undermines public knowledge and discourse. The fact that China is lodging allegations of US espionage operations is still notable, providing insight into the relationship between the US and China, even if China does not support its claims. CTI analysts and intelligence consumers would be wise to differentiate between the claims made by China across domains, however.

To date, China has provided no reasonable evidence to support any of its claims besides wantonly recycling leaked US intelligence. In western cybersecurity industry circles, claims of US hacking without supporting technical evidence are derided—and rightfully so.

State secrecy laws are the likely culprit stopping PRC-based cybersecurity companies from publishing technical data. With their hands tied, the CCP’s political mandate to support narratives of western espionage operations leaves its companies hamstrung. We can and should call out this lack of rigor when we see it, ensuring that claims made by Chinese firms and the government are held to the same, rigorous analytical standards the global cybersecurity community has self-imposed.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh