2024-2-24 00:17:7 Author: techcrunch.com(查看原文) 阅读量:21 收藏

Over the weekend, someone posted a cache of files and documents apparently stolen from the Chinese government hacking contractor, I-Soon.

This leak gives cybersecurity researchers and rival governments an unprecedented chance to look behind the curtain of Chinese government hacking operations facilitated by private contractors.

Like the hack-and-leak operation that targeted the Italian spyware maker Hacking Team in 2015, the I-Soon leak includes company documents and internal communications, which show I-Soon was allegedly involved in hacking companies and government agencies in India, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Pakistan, Taiwan and Thailand, among others.

The leaked files were posted to code-sharing site GitHub on Friday. Since then, observers of Chinese hacking operations have feverishly poured over the files.

“This represents the most significant leak of data linked to a company suspected of providing cyber espionage and targeted intrusion services for the Chinese security services,” said Jon Condra, a threat intelligence analyst at cybersecurity firm Recorded Future.

For John Hultquist, the chief analyst at Google-owned Mandiant, this leak is “narrow, but it is deep,” he said. “We rarely get such unfettered access to the inner workings of any intelligence operation.”

Dakota Cary, an analyst at cybersecurity firm SentinelOne, wrote in a blog post that “this leak provides a first-of-its-kind look at the internal operations of a state-affiliated hacking contractor.”

And, ESET malware researcher Mathieu Tartare said the leak “could help threat intel analysts linking some compromises they observed to I-Soon.”

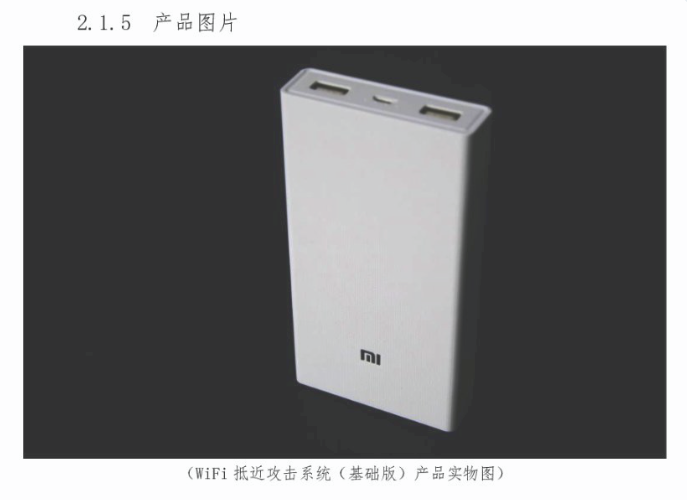

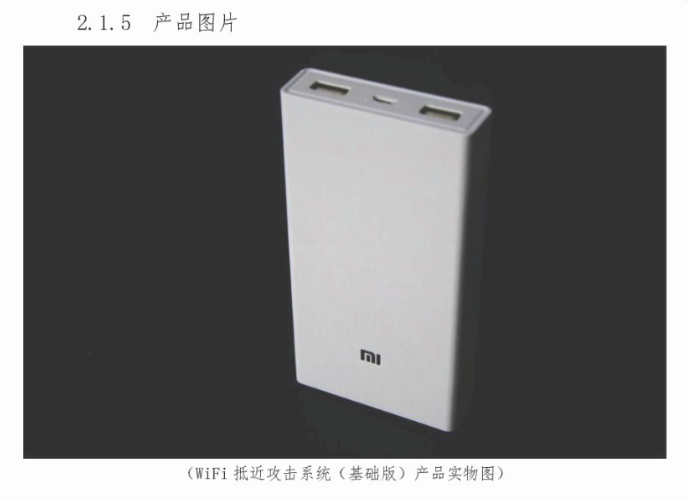

One of the first people to go through the leak was a threat intelligence researcher from Taiwan who goes by Azaka. On Sunday, Azaka posted a long thread on X, formerly Twitter, analyzing some of the documents and files, which appear dated as recently as 2022. The researcher highlighted spying software developed by I-Soon for Windows, Macs, iPhones and Android devices, as well as hardware hacking devices designed to be used in real-world situations that can crack Wi-Fi passwords, track down Wi-Fi devices and disrupt Wi-Fi signals.

I-Soon’s “WiFi Near Field Attack System, a device to hack Wi-Fi networks, which comes disguised as an external battery. (Screenshot: Azaka)

“Us researchers finally have a confirmation that this is how things are working over there and that APT groups pretty much work like all of us regular workers (except they’re getting paid horribly).” Azaka told TechCrunch, “that the scale is decently big, that there is a lucrative market for breaching large government networks.” APT, or advanced persistent threats, are hacking groups typically backed by a government.

According to the researchers’ analysis, the documents show that I-Soon was working for China’s Ministry of Public Security, the Ministry of State Security, the Chinese army and navy; and I-Soon also pitched and sold their services to local law enforcement agencies across China to help target minorities like the Tibetans, and the Uyghurs, a Muslim community that lives in the Chinese western region of Xinjiang.

The documents link I-Soon to APT41, a Chinese government hacking group that’s been reportedly active since 2012, targeting organizations in different industries in the healthcare, telecom, tech and video game industries all over the world.

Also, an IP address found in the I-Soon leak hosted a phishing site that the digital rights organization Citizen Lab saw used against Tibetans in a hacking campaign in 2019. Citizen Lab researchers at the time named the hacking group “Poison Carp.”

Azaka, as well as others, also found chat logs between I-Soon employees and management, some of them extremely mundane, like employees talking about gambling and playing the popular Chinese tile-based game mahjong.

Cary highlighted the documents and chats that show how much — or how little — I-Soon employees are paid.

Contact Us

Do you know more about I-Soon or Chinese government hacks? From a non-work device, you can contact Lorenzo Franceschi-Bicchierai securely on Signal at +1 917 257 1382, or via Telegram, Keybase and Wire @lorenzofb, or email. You also can contact TechCrunch via SecureDrop.

“They’re getting paid $55,000 [US] — in 2024 dollars — to hack Vietnam’s Ministry of the Economy, that’s not a lot of money for a target like that,” Cary told TechCrunch. “It makes me think about how inexpensive it is for China to run an operation against a high-value target. And what does that say about the nature of the organization’s security.”

What the leak also shows, according to Cary, is that researchers and cybersecurity firms should cautiously consider the potential future actions of mercenary hacking groups based on their past activity.

“It demonstrates that the previous targeting behavior of a threat actor, particularly when they are a contractor of the Chinese government, is not indicative of their future targets,” said Cary. “So it’s not useful to look at this organization and go, ‘oh they only hacked the healthcare industry, or they hacked the X, Y, Z industry, and they hack these countries.’ They’re responding to what those [government] agencies are requesting for. And those agencies might request something different. They might get business with a new bureau and a new location.”

The Chinese Embassy in Washington, D.C. did not respond to a request for comment.

An email sent to the support inbox of I-Soon went unanswered. Two anonymous I-Soon employees told the Associated Press that the company had a meeting on Wednesday and told staffers that the leak wouldn’t impact their business and to “continue working as normal.”

At this point, there is no information about who posted the leaked documents and files, and GitHub recently removed the leaked cache from its platform. But several researchers agree that the more likely explanation is a disgruntled current or former employee.

“The people who put this leak together, they gave it a table of contents. And the table of contents of the leak is employees complaining about low pay, the financial conditions of the business,” said Cary. “The leak is structured in a way to embarrass the company.”

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh