In the modern world, we are surrounded by a multitude of smart devices that simplify our daily lives: smart speakers, robotic vacuum cleaners, automatic pet feeders and even entire smart homes. Toy manufacturers are striving to keep up with these trends, releasing more and more models that can also be called “smart.” For instance, educational robots that connect to the internet and support video calls. Our colleagues kindly provided us with a robot like that for research purposes, as they wanted to ensure that the toy their children played with was sufficiently protected against cyberthreats. During our analysis, we discovered several vulnerabilities that allow malicious actors to gain access to confidential data and communicate with children without their parents’ knowledge.

Subject of the study: educational robot

The toy is designed to educate and entertain children; it is an interactive device running the Android operating system. It can move and has a big color screen, a microphone, a video camera and other features. In other words, this is a “tablet on wheels.” Interactive features include gaming and educational applications for children, a voice assistant, internet access and connection to the parent app for smartphones.

Possible attack vectors

Parents app

The robot needs to be linked to a parent’s account before it can be used. The parent application must be installed on the parent’s mobile device in order to accomplish this. From a security researcher’s perspective, this application is particularly interesting because it allows calling to the robot, and monitoring the child’s activities and learning progress.

Toy

The robot connects to a home Wi-Fi network and interacts with the application through the internet. Upon initial setup and internet connection, the robot prompts for a software update to the latest version and will not function without one. However, we decided not to update the toy immediately in order to explore what could be extracted from the older firmware version.

Internal structure review of the robot

Analysis of schematics and component base

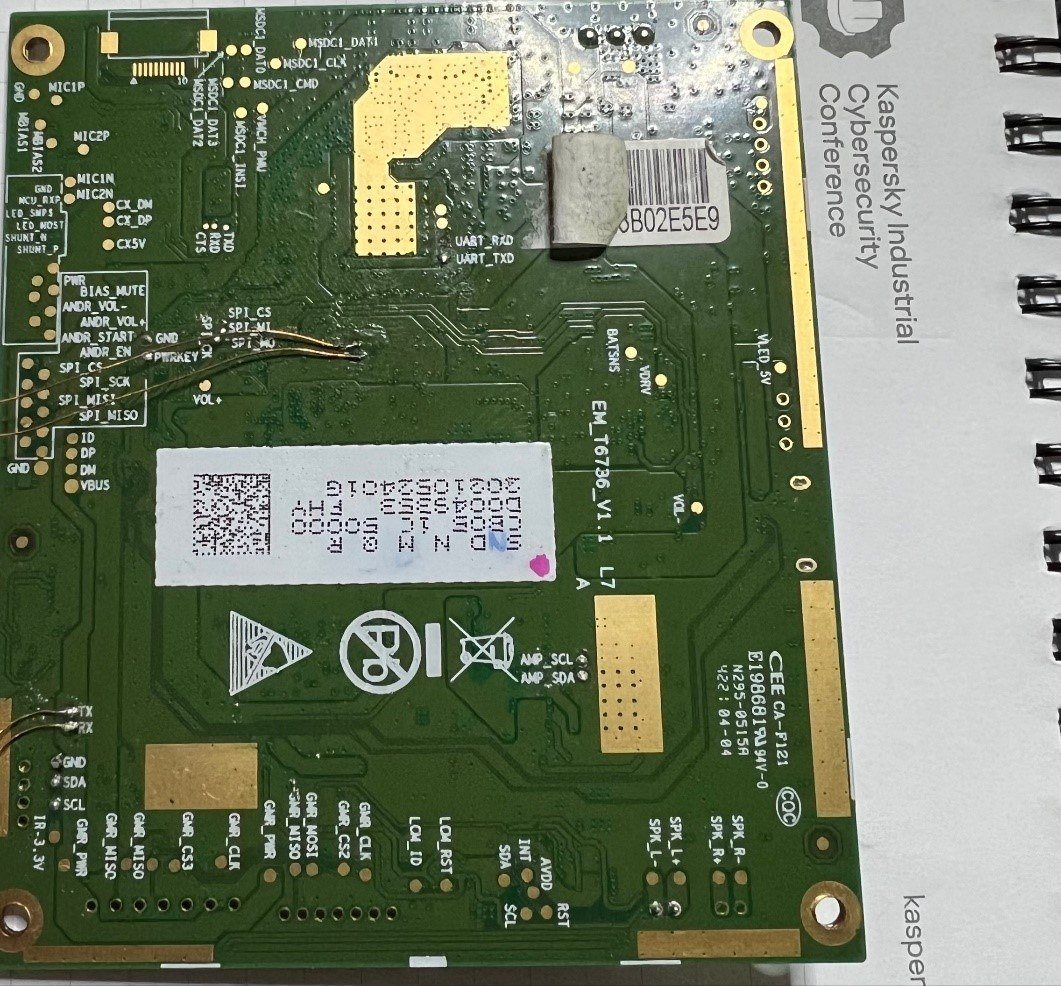

We want to express our gratitude to the manufacturer for their assistance in conducting a schematic analysis of the robot’s electronic components. All the connectors, ports and test pads on the boards were labeled, which is not too common. Among a variety of connectors, the USB connector labeled as “Android” (see the peripheral management board photo) caught our attention, as well as a number of interfaces typically used for firmware debugging.

Main board top view

| Number | Marking | Purpose |

| 1 | MediaTek MT8167A 2117-BZASH | Main chip |

| 2 | MediaTek MT7658MSN 2128-BZASL | Dual-band Wi-Fi 802.11ac MU-MIMO and Bluetooth 5.0 |

| 3 | MediaTek MT6392A 2024 | Power management for MT8167 platform |

| 4 | Conexant CX20921 | Voice input processor |

| 5 | WinBond 25Q64JWIQ | 64Mb SPI Flash for voice input processor |

| 6 | Royson RS256M32LD | LPDDR3 SDRAM 8Gb RAM |

| 7 | KOWIN KASA6211 | 32Gb eMMC Flash for MediaTek MT8167A processor |

| 8 | 40-pin connector | Connector |

Peripherial management board

| Number | Label | Purpose |

| 1 | TI MSP432P401R | Microcontroller for peripheral control |

| 2 | 40-pin connector | Connector |

Main board bottom view

Initial robot setup and network traffic analysis

Upon initial setup, the toy prompts the user to select a Wi-Fi network, connect the robot to the parent’s mobile device, and enter minimal information about the child who will be using the toy, such as the name and age. This information is delivered in plaintext via the HTTP protocol, making it vulnerable to interception by network traffic analysis software, as we observed while examining early network traffic.

Additionally, certain network requests piqued our interest:

login_user request to get access_token with a correct password

The request in the screenshot above retrieves an access token to the API based on the following authentication data: username, password and key. In fact, a valid token is returned even if we provide incorrect credentials. This was the first security-related issue we discovered.

login_user request to get access_token with an incorrect password

The next request returns configuration parameters for the specific toy based on its unique identifier, consisting of nine characters. For the analyzed model, the identifier always starts with “M3.”

GetAppConfiguration request to get the configuration file

The robot identifier used in API requests has a format similar to the alphanumeric identifier printed on the robot’s body, known as P/N:

Robot IDs indicated on the case

Such a low entropy ID allows for complete enumeration of all the possible identifiers. As a result, an attacker can obtain information about various robots and their owners, such as their IP addresses, countries of residence, names, genders and the children’s ages.

In addition to the user data, the server sends a considerable amount of configuration settings in response to the request, including access keys to external service APIs, such as QuickBlocks, Azure and Linode, that the robot uses during its operation. These settings are stored to the robot, in a file located in the internal memory. We will further examine its contents in more detail.

The next request, in response to the same identifier, returns some user data, such as the email address, parent’s phone number, and a code for linking the parent’s mobile device to the robot.

CheckAuthentication request to verify the robot’s binding to the parent application

As part of the initial setup and configuration, the robot persistently requested a software update, prompting us to perform the update for the child to study using the most up-to-date and relevant version.

After the robot’s software was updated, the aforementioned requests, which previously had been transmitted through the insecure HTTP protocol, started using the secure encryption protocol HTTPS. Thus, in order to further analyze this network traffic, it is necessary to conduct a MitM attack capable of circumventing the encryption.

Analyzing the file system

Analyzing eMMC Flash content

There are various methods for conducting a MitM attack on device network traffic. We decided to make use of the Android Debug Bridge (ADB), a tool for debugging devices running the Android OS.

ADB allows:

- Viewing debugging messages from the Android OS and applications running on the device

- Copying files to and from the device

- Installing and uninstalling applications

- Wiping and overwriting the data partition in the device’s memory

- Executing various scripts

- Managing certain network parameters

We planned to use ADB to modify the robot’s file system and install SSL certificates to be able to access the cleartext traffic. To determine how to enable ADB on the device, we decided to read the contents of the memory chip.

By obtaining and analyzing the file system image, we learned the following:

- During the system boot, the Android OS configuration file specifies the launch of adbd (the ADB daemon responsible for executing commands on the device) with root privileges.

- At the startup stage, the robot is briefly recognized as a USB device with ADB access.

- After the Android OS starts, a configuration is applied in which only the MTP service is activated on the USB. The ADB service is disabled.

ADB Activation

We analyzed the configuration files contained in the firmware memory chip and found a setting called “ENABLE_ADB=N.” After changing this setting to “ENABLE_ADB=Y,” we were able to activate ADB and work with it until the robot connected to the server, where it loaded a new configuration that set the default value (“ENABLE_ADB=N”).

As a result of activating ADB, we gained the ability to analyze the system behavior in the operational toy, view open network ports and running applications, and initiate a detailed investigation of these.

Analysis of Video Streaming API

Developers used the cloud service Agora to support calls between the robot and a parent’s mobile device. It was not difficult to identify this, as mentions of Agora could be found in the configuration file that the server provided to the device in response to the GetAppConfiguration request. This file is stored unencrypted in the file system:

Configuration of the Agora cloud service

The Django REST Framework is used extensively in the server-side API, which the robot communicates with via HTTP queries. It is worth noting that during the investigation, we found that an oversight by the vendor’s developers allowed the framework to be configured in debug mode on the production servers. This unintentional configuration exposed detailed descriptions of all API endpoints and error messages, containing a significant amount of debugging information. As an example, we provide a page with a description of the Agora token retrieval request, which is required for establishing a connection with the robot:

REST API response to Agora token request with an error description

Making a call to any robot

The algorithm for establishing a connection between the parent application and the robot is as follows:

- The parent application initiates a request in the following format:

Request to get a token for the Agora API session

In response, the server generates an Agora Token, which the application can use to connect to the call through the Agora service. The user_id parameter can be randomly selected, while the robot ID is passed in the channel_name parameter. Through experimentation, we found that when processing a request for Agora token generation, the vendor’s server does not verify whether this ID corresponds to the robot associated with the current authorized user. Furthermore, the server does not verify if the request is authorized at all.

As a result, a malicious actor who sends the type of request described above can get an Agora token and start a video conversation with any robot using only the robot’s easily guessable identifier.

- The following data must be provided to connect to an Agora service call:

- The token received from the vendor’s server

- The “room” name (channel_name), which is the robot’s identifier

- Agora APP ID: the identifier of the application using the Agora API, which is the same for all robots of the same model and the parent application

- Once connected to Agora, an unauthorized user can send the following request to the vendor’s server, as shown in the screenshot:

Request to send a video call to the robot

The robot with the specified ID (username parameter) will display the incoming call:

Incoming call to the robot

If the child accepts this call, the perpetrator will be able to talk to them without the knowledge of their parents, potentially luring them out of their home or pushing them towards risky actions. Therefore, the lack of proper security checks when establishing a video session with a children’s educational robot puts the child at risk while playing with it.

Update process

During the update process, the robot downloads an archive called “APPS.z” from the cloud. It contains a command-line script responsible for unpacking and installing the update.

RCE (Remote Code Execution) during the update process

The unpacking and installation script is contained in a file with the extension “*.l” and has the following format:

The script for unpacking an update file

Since the update file lacks a digital signature, in theory, a malicious actor could launch an attack on the update server and replace the archive with a malicious one. This would grant them the ability to execute arbitrary commands on all robots with superuser privileges.

Parent hijacking

A malicious actor can link an arbitrary device to their own account, causing the parent’s account to lose access to the robot. To restore the legitimate connection, the parent will need to contact the manufacturer’s technical support.

The attacks involving robot re-binding occur as follows:

- By invoking the checkAuthentication method, the malicious actor obtains the owner’s email and phone number using the device identifier, which can be obtained through brute force.

CheckAuthentication request to receive the owner’s email and phone number

- The perpetrator attempts to authenticate using the received email or phone number. The authentication process involves a weak one-time password (OTP) consisting of six digits, with unlimited input attempts.

The process of authorization with OTP on a mobile device

- After brute-forcing the OTP code and authenticating successfully, the perpetrator can disconnect the robot from the parent device, as shown in the screenshot below.

Unbinding the robot from the parent application

- The offender can then remotely connect the robot to their own account. The OTP generated by the toy must be entered as displayed in the image:

Password for synchronization generated by the robot

An attacker can obtain this code by calling the checkAuthentication method, knowing only the device identifier: the password field in the server response contains the OTP.

CheckAuthentication request to get an OTP code

Communications with the vendor

What was nice, the vendor reached out and took responsibility for all the security issues that had been reported to them. They provided the required instructions and fixes to ensure robust data protection and to prevent any misuse of the toy. Thanks to their efforts, opportunities for potential attackers were eliminated.

Timeline

- March 27, 2023: security issues reported to vendor

- April 13, 2023: vendor accepts report for verification

- July 24, 2023: vendor acknowledges security issues

- August 18, 2023: security issues fixed by vendor

Conclusion

The research has revealed a number of vulnerabilities in the toy’s API that malicious actors can use to steal sensitive information:

- child’s data

- country and city of residence

- phone number

- parents’ email address

An attacker can even gain unauthorized access to the robot and re-register it in their own name. Insufficient security measures in a children’s toy against information security threats can have serious consequences. Unauthorized remote access to this kind of device further opens up possibilities for cyberbullying, social engineering and exploitation of children’s trust. Furthermore, exploiting the toy’s vulnerabilities can lead to leakage of sensitive information and even videos made inside the home.

To avoid these risks, parents should carefully choose smart toys and regularly update their software. Manufacturers of these toys, in turn, should thoroughly test the security of their products and infrastructure, and responsibly inform customers about potential threats.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh