2024-6-17 21:0:29 Author: www.sentinelone.com(查看原文) 阅读量:8 收藏

Last week, PinnacleOne highlighted how a new turn of phrase by China’s leader will spark efforts across the country to make scientific breakthroughs occur out of thin air (or steal them from the west).

This week, we flag three emerging threats to the “deep tech” venture ecosystem underpinning western technological and strategic advantage.

Please subscribe to read future issues — and forward this newsletter to interested colleagues.

Contact us directly with any comments or questions: [email protected]

Throughout the 20th century, most strategic technologies were incubated or directly invented by the Federal Government or by contractors and academic institutions under its protective umbrella. Not anymore.

Now, many cutting edge technologies of strategic and foundational importance (in AI, robotics, quantum, biotech, space, materials, and new energy) are spawned in a diffuse private ecosystem. Instead of well-resourced government programs of the 1950s-1990s, small teams of founder scientists and engineers convince “deep tech” venture capitalists they have caught lightning in a bottle. In venture capital jargon, “deep tech” signals that a company’s business model relies on significant advances in science and technology. Adversaries and cybercriminals are also catching on. We see them aggressively targeting these startups for their post-funding round cash, critical IP, proprietary R&D, and talented expertise.

Pre-IPO deep tech firms and their VC backers now face a fundamentally different threat environment than those of decades past. Decisions made now to protect themselves are critical not only to future investment rounds and successful exits, but also for the technological advantage of western liberal democracies confronting an acute and aggressive authoritarian challenge.

Those working in the cutthroat trenches of venture capital or the worktop benches of a deep tech startup understand risk. It is the essential premise of the outsized returns that motivate their high pressure endeavors, where failure is the baseline expectation. However, there are three emerging risks that are not currently priced into most venture valuation models: Criminals, China, and Co-Opters.

Criminals

“[VOWELLESS] startup today announces a $15M Series A funding round led by [blue chip VC firm] with participation by [Sand Hill Road standbys…]”. Such a headline tells a certain cohort of aggressive cybercriminals that this specific company (whose infosec staff is so small they can probably share an appetizer) now has millions in the bank and a cohort of deep-pocketed investors deeply motivated to make any incident quickly and quietly go away.

All it takes is a willingness to commit crimes, teenage hubris, some googling, off-the-shelf ransomware tools, and maybe some AI-assisted social engineering and presto… payday. The thing about such targeting trends among cybercriminals is that a successful tactic spawns imitators and what may now be a very quiet and limited circle of victims could expand quickly. The lack of headlines on this issue is likely a result of incentives to keep things secret, not an evidence of absence.

China

President Xi has given marching orders to his scientific, economic, and security bureaucracies to seize the “commanding heights” of technology development and make China into the “World’s Primary Center for Science and High Ground for Innovation.” Xi aims to leap ahead to the frontier of emerging technologies he sees driving a “S&T and industrial revolution” and critical to the “new quality productive forces” that will accrue strategic advantage to those nations in the lead position.

In Xi’s words, “creative breakthroughs in areas such as information technology, life sciences, manufacturing, energy, space, and maritime are supplying ever more wellsprings of innovation for cutting-edge and disruptive technologies…and S&T have never before so profoundly influenced the future and fate of nations.”

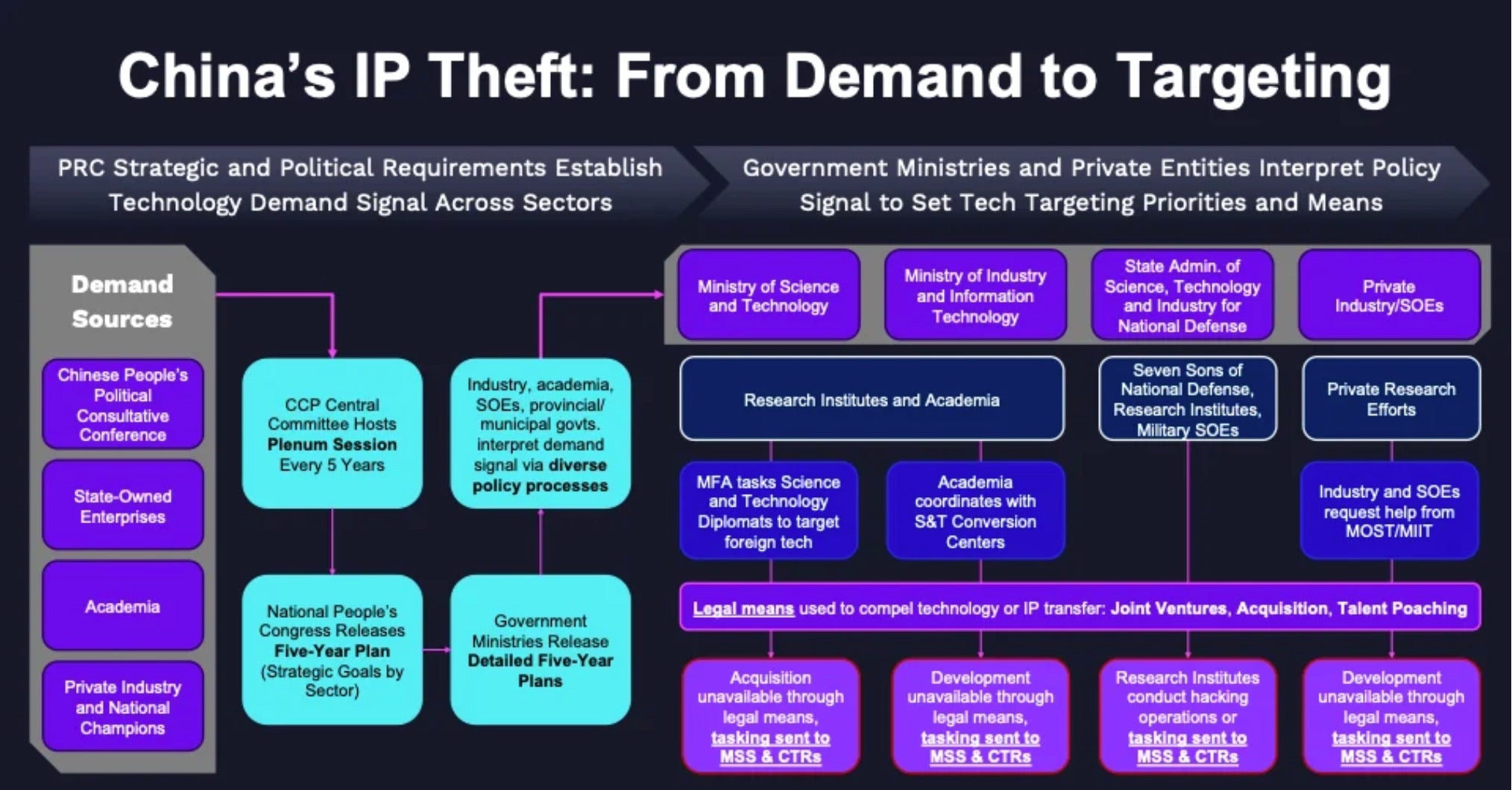

As described in a previous post on China’s hacking ecosystem, this top-level strategic demand signal drives an all-of-government (and commercial) effort to acquire (by any and all means, overt or not) the West’s technical crown jewels, many of which are being cut and polished by small startups in Silicon Valley and the “Gundo”.

For example, while it’s very cool to develop a breakthrough jet engine that could change the economics of space launch, posting your workshop location and part designs, and identifying key personnel roles along with your seed funding and backers is likely to invite unwarranted attention. We understand the important function hype and in-group social visibility play in early-stage venture success, but Lockheed engineers don’t post on X from their secret commuter plane flying into the Nevada desert for a reason.

If you want to play in the critical tech big leagues – or invest in it – and overtly signal the strategic value of your R&D, understand that your threat model isn’t that of a standard SaaS startup. If you claim your technology to have a strategic impact on competition between nations, expect strategic APTs.

Co-Opters

China isn’t the only nation looking to capture the frontier of these emerging technologies. The UAE and Saudi Arabia have lofty ambitions of their own, as we detailed in our earlier post on the new digital great game in the Middle East. While political “decoupling” has severed many of the (direct) venture links between China and the U.S., the western VC ecosystem has now “recoupled” to these deep-pocketed Gulf powers.

The private jets landing in Riyadh, Abu Dhabi, and Dubai over the last two years include a veritable who’s-who of leading deep tech VC players. It is hard to pass up on a nine or ten figure check from a sovereign wealth fund or royal UHNWI (ultra-high net-worth individual), even if the conditions require they be made sole limited partners of standalone funds, maybe at the expense of existing domestic limited partners (LPs).

These domestic LPs tend to be pension funds, family offices, endowments and other wealthy entities with no objective other than maximizing financial returns. But there is a key difference. These new Emirati and Saudi LPs are deploying state capital with a different objective: to scout, nurture, and accelerate critical technologies they intend to co-opt for their own national advantage, in line with their national strategic visions and economic innovation plans.

We are aware that some of these LPs receive detailed non-public reports on their investments, including not only the value of fund portcos, but closely-held R&D strategies, key hires, product roadmaps, high value customers and planned partnerships (which may include the U.S. and allied governments), technical dead-ends and imminent breakthroughs. This information is an S&T intelligence targeting officer’s dream and would provide a critical advantage to adversary aligned competitors looking to fast-follow western tech firms exploring the difficult and capital-intense scientific frontier.

We are also aware of firms leading in strategic and scientifically prized technology domains being “encouraged” by their Gulf backers to set up domestic R&D teams co-located at national universities where Chinese researchers just happen to be lab neighbors working on very similar projects. This is a remarkable coincidence to say the least.

The self-serving argument, for now, is that this is a win-win marriage of convenience between Gulf capital and Western venture, and that while the money buys some influence, the fundamental advantage and leverage remains where the brains and tech come together. This may be the case at the moment, but the trend of structural deep tech venture dependence on Gulf capital seems to be only going one way. The nature of addiction is that each hit can be justified in the moment, even if one knows it is ultimately self-destructive.

Risk-Return

Deep Tech seed investments typically have a longer horizon for return than B2B products or SaaS apps and rely disproportionately on the talents and insights of a small team of highly technical founders (often scientists and engineers). Additionally, the path to growth (especially in military, intelligence, and adjacent dual-use application spaces) often weaves through government programs or related defense technical primes that buffer the “valley of death” between prototype and product-market fit. This exposes such startups and their VC backers to more “key man” and “loss of competitive edge” risk than typical software ventures that rely less on a scientific edge than on sales, partnerships, and platform scaling strategies.

The standard practice of USG-affiliated deep tech venture activities like the Defense Innovation Unit, In-Q-Tel, as well as the venture arms of major defense and intelligence contractors (like Booz Allen Hamilton, Lockheed, etc.) has been to scout and quickly incorporate leading edge tech under their protective umbrella (experienced as they are with managing sensitive R&D programs at acute risk of adversary compromise). In some cases, truly disruptive startups are known to “disappear”, their technology tucked behind the classification curtain, and their patents classified.

Such protections are now the exception, not the rule, for the breakthrough technologies emerging from the U.S.’s venture engine of innovation. In most cases, their teams, tech, and tools are in full public view, if not aggressively hyped as the foundation for strategic national advantage. It is high time these firms and their funders wake up to the fact that they are squarely in the crosshairs, before this advantage bleeds away to illiberal authoritarians and U.S. adversaries.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh