2024-7-18 22:1:26 Author: therecord.media(查看原文) 阅读量:5 收藏

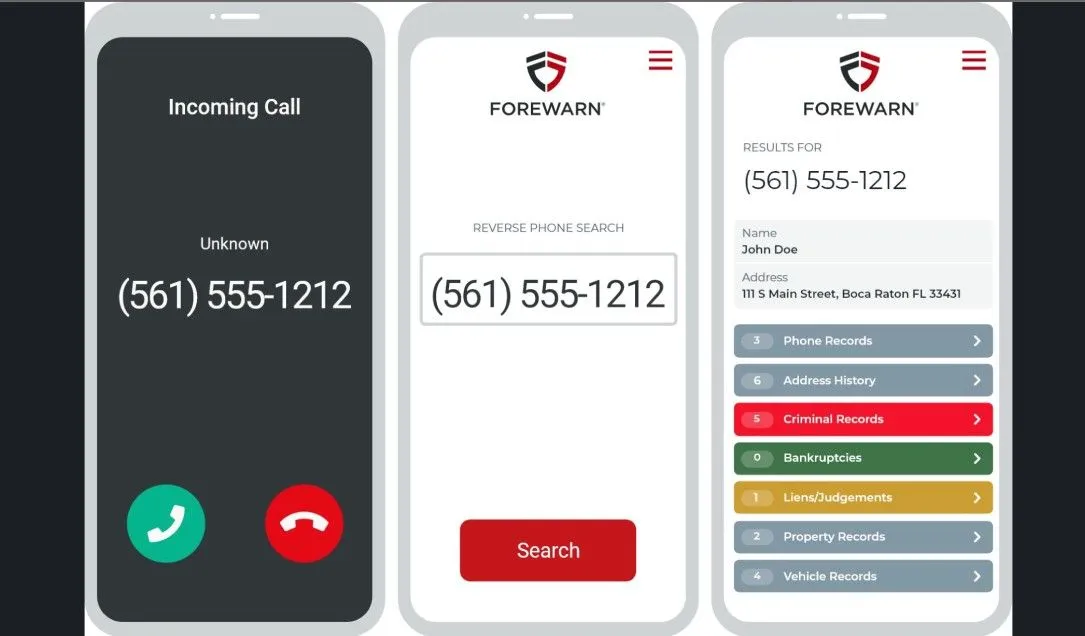

When Florida real estate professional Susan Hicks discovered the app Forewarn over a year ago, she was shocked to learn that for a service costing about $20 a month she could instantly retrieve detailed data on prospective clients with only their phone number. “For anybody who's had exposure to this, usually the first time they see it, it blows their mind,” Hicks told Recorded Future News, adding that she enthusiastically recommends the tool to the brokers she manages. “It's incredible that there's that amount of information out there that you can just access with one click.” “It can be real creepy and you have to swear that you’re not going to use it in a wrong manner,” Hicks added, referring to Forewarn rules which say real estate agents can’t share data from the app publicly or with third parties, or use the app to pull information on non-professional contacts. Forewarn is primarily marketed to and used by the real estate industry, and it has been penetrating that market at a rapid clip. Although some real estate agents say the financial information it returns saves time when finding clients most likely to have the budget for the houses they’re looking at, most agents and associations tout it primarily as a safety tool because it also supplies criminal records. In addition to those records, the product — owned by the data broker red violet — also supplies a given individual’s address history; phone, vehicle and property records; bankruptcies; and liens and judgements, including foreclosure histories. Although such data could generally be gleaned from public records, Forewarn delivers it at the press of a button — a function real estate agents say allows them to gather publicly available information without having to visit courthouses and municipal offices, a process which would normally take days. The power of Forewarn’s technology has led to rapid adoption, but the company is still largely unknown outside the real estate industry. Several fair housing and civil rights advocates interviewed by Recorded Future News weren’t aware of its existence. The individuals whose data it sells also have no idea their information is being shared with real estate agents, who potentially might choose not to work with them because of what they discover on the app. Forewarn did not respond to multiple requests for comment, however, statements made by one of its executives suggest that the company intentionally keeps a low profile. “Do not tell the prospect that they are not permitted or unqualified to purchase or sell property because of information you obtained from Forewarn,” a company executive said at a recent training webinar with Illinois real estate agents. She emphasized that potential buyers “do not get notified” when they are screened with the app, a question she said many real estate agents ask. Real estate agents who, for example, discover a client has a lien filed against them, should consider telling the prospect they “obtained this information from a confidential service that bases their information on available public record information,” the executive added. As Forewarn continues to penetrate the real estate industry, one of the biggest questions for the company is whether it will be able to evade scrutiny and pushback by privacy advocates who say it is essentially mass profiling renters and potential homebuyers in silence, as well as regulators who have cracked down on similar practices. Last year, real estate associations and management listing services (MLS) in Florida (238,000 members), Georgia (52,000 members), South Carolina (29,000 members) and Houston (48,000 members) contracted with Forewarn. MLSs and associations covering Nashville (6,000 members), New Orleans (6,600 members), San Antonio (13,000 members), Columbus (9,000 members), Savannah (2,500 members), Florida’s Space Coast (6,000 members), North Carolina’s Research Triangle (15,000 members) and Greater Alabama (6,500 members) also signed on, according to Forewarn’s Facebook page. More than 425 real estate associations had contracts with Forewarn as of this May, the company said in a press release. “It's definitely a valuable tool, “ said Houston Association of Realtors Vice Chair Theresa Hill, who noted that her realtors benefit from easily accessing both criminal and financial records through the app. “Some of this is public records, but you would probably have to go fishing for it and go to several different sources,” she said. Hill noted that her association’s agents abide by a strict code of ethics. Some real estate agents specialize in helping buyers with a history of foreclosures, she said, emphasizing that those with checkered financial histories are not discriminated against. While most of the five Forewarn-equipped realtors or real estate association heads whom Recorded Future News spoke with said they primarily use the app for criminal records checks, that information populates only one of eight data sets the product instantly supplies. The rest, with the exception of phone records, are financial indicators. Profits at red violet increased by 20% in the first quarter of 2024 compared to the year prior, with the company earning $17.5 million in total revenue, according to a company press release. Forewarn is one of red violet’s two brand offerings, according to its LinkedIn page, which says between 51 and 200 people work there. Forewarn has no direct competitors offering the same targeted and instantly, easily digestible data services that are packaged and marketed to real estate agents — particularly without notifying clients they are being screened. Image: Forewarn “Its data offering is more powerful, instantaneous and widely adopted than any other real estate app in existence,” said data broker expert Jeff Jockisch, who added the caveat that if something more powerful is available “it's so small that nobody's actually using it.” “The real estate agent can essentially screen out people they don't want by saying, ‘Oh, this person drives a Ford truck and I only want to sell to high end people so I'm just gonna get rid of this customer,’” Jockisch said in an interview. “They are putting instantaneous background assessments — lots of information about a person, some of which might not be true — in the hands of regular citizens, people who may not be equipped to use that information without bias,” Jockisch added. Hicks, the Florida real estate team leader, disputed Jockish’s assertion, saying it would be unethical to only use Forewarn’s data to determine whom to work with. As part of her job, Hicks is responsible for ensuring the realtors she manages are as financially successful as possible. She called the app one of many helpful tools available and said her employees would never weed out a client based on its findings. But she also acknowledged that the type of financial information Forewarn provides would spur her to think twice about spending a lot of time working with someone. “If you can clearly see that somebody's been arrested in the past two, three years, chances are pretty good their credit score is not good,” said Hicks, who noted that as a manager she is not actively selling properties, though she has in the past. “Everybody's situation is different, and we're supposed to be honest and fair with the public,” Hicks said. “You can’t take it as gospel … You can’t judge people solely on [Forewarn].” “But I wouldn't spend a lot of time with somebody that's had a couple of bankruptcies,” she added. “I wouldn't put them in my car and drive them all around and show them property and waste a day.” While Forewarn most heavily markets its data’s ability to make real estate agents safer, the company also promotes the “smarter engagements” it facilitates for agents “risking their safety and their time.” In addition to praising the safety protections the app offers, as Hicks and many others did, some real estate agents said Forewarn is helpful for fighting scams because it allows them to verify that callers are who they say they are from the outset — a benefit Forewarn touts in its promotional materials. In the past, criminal and financial verification methods have been rarely used in the real estate industry “due to the time and cost traditionally associated with such an exercise,” a Forewarn YouTube promotion said. “With Forewarn, prospect verifications are instant,” the ad says. “Know your prospect in seconds.” The promotional video says the app can identify more than 90% of the population with only a phone number and more than 98% with a phone number and additional information. Forewarn uses auditors to ensure that rules such as only making professional searches and not sharing data with third parties are followed, the company executive speaking at the webinar said. She added that when the auditors find agents abusing the app, they cut off their access to it. The company’s terms and conditions contain warnings about how to properly use the product, including by telling real estate agents to “protect against unauthorized access to or use of such information that could result in substantial harm or inconvenience to any consumer.” Meanwhile, though the safety risks Forewarn highlights in the promotional video are not without merit, there is debate over whether Forewarn can mitigate the most serious concerns. In 2020, a Roanoke, Virginia, real estate agent was hit with a wrench 10 times during an open house, an attack that an arrest warrant said left her with “permanent and significant physical impairment.” Her attacker also was accused of attempted rape. Katy Cookston, a real estate agent working nearby, said the incident deeply shook her and she has embraced Forewarn as a result. “Being a mom comes first for me so I had to make sure that I was going to get home at the end of the day,” Cookston said in an interview. However, it is unlikely Forewarn would stop such an attack since it happened during an open house, where unidentified people routinely enter vacant homes for tours without advance warning. The fact that real estate agents feel unsafe meeting clients for home tours that are not open houses strikes Washington, DC agent Dave Van Leeuwen as odd since real estate agents should have multiple conversations with buyers prior to entering vacant homes and are supposed to obtain a signature from a new client in advance of giving tours. “All of this should happen before any properties are visited,” Van Leeuwen added. Despite Forewarn’s explosive growth, it has largely stayed under the radar. Four fair housing experts with major civil rights organizations contacted by Recorded Future News had not heard of the app. A fifth said he had become aware of it by chance at a Houston real estate agent conference on artificial intelligence the prior week. But the app is likely to begin attracting attention because it is distinct from other offerings in the housing marketplace, data privacy attorney Heidi Saas said. Forewarn offers easy to visually digest “identity graphs,” which Saas said are different from “just finding a spreadsheet with a couple of data points about somebody. The identity graph is everything you do all day, every day in the virtual world, in one spot.” The app also is cloud native, she said, which means there are no limits to how much the product can scale. While tenant screening data products have been longtime targets for fair housing advocates, unlike with Forewarn, in most cases prospective renters are made aware of those background checks and can challenge inaccurate facts if they are denied a lease, housing experts said. Traditional tenant screening checks also do not typically deliver the instantaneous results Forewarn does. Because poor, black or Latino people seeking real estate agents will likely never know if they have been profiled by agents using Forewarn, and are therefore potentially being ignored without knowing why, the app can facilitate discrimination and further widen the already large gap between white homeowners and those who are Black or in other minority groups, according to Ridhi Shetty, an expert on discriminatory data practices and policy counsel with the Center for Democracy and Techology's Privacy & Data Project. Across the U.S., Black households are far less likely to own homes compared to white households, partly due to discrimination at every level of the homebuying process. Experts say it is easy to see how Forewarn could make it much harder to reverse that phenomenon. Longtime Mississippi real estate agent Bill Anton said he has been using Forewarn for more than two years and it “can certainly be a red flag if you start seeing a lot of financial problems on someone.” But Forewarn has proven to lag when it comes to updating vital financial information, he said, even as he hailed the app for its safety benefits. Anton has found a lot of bankruptcies are “cleared up and not currently on their [prospects’] record anymore, although they're showing up on the Forewarn app.” The company’s terms and conditions explicitly say that Forewarn does not guarantee its data’s “accuracy, currentness, completeness, timeliness, or quality … The services are provided ‘AS IS.’” Forewarn parent company red violet has been sued for allegedly supplying inaccurate data in the recent past. The data broker also owns IDI, a cloud native company which calls itself an “industry-leading identity intelligence platform,” according to its website. Forewarn appears to use the same IDI “proprietary CORE technology that leverages massive, unified data assets, machine learning, and advanced analytical capabilities” to serve its clients’ data needs, according to red violet’s website and Forewarn press releases. A class action lawsuit filed against IDI in 2022 focused on how the company flouts the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) by saying it is not a consumer reporting agency. The named plaintiff in the case, Tabitha Parker, lost a job because IDI mixed her up with a criminal, the lawsuit said. An IDI background check report said Parker was guilty of a second-degree felony for aggravated battery on a pregnant woman. But Parker had never been charged with a felony and a mugshot included in the IDI report is not Parker, according to the lawsuit. The lawsuit focused on the fact that IDI “unilaterally (and illegally) decided the reports it sells do not qualify as ‘consumer reports.’” As a result, the lawsuit said, Parker and the other class members were not protected by FCRA, which gives people several important protections when buying or renting a home or maintaining eligibility for a job. Forewarn’s website login page states in bright red letters that it is not a consumer reporting agency and suggests that it is therefore not covered by FCRA — a claim privacy and data broker experts disputed. “If Forewarn is disclaiming any responsibilities under FCRA, it’s likely they’re not using legally sufficient procedures to ensure the accuracy of the consumer information or giving consumers a reliable way to dispute inaccurate information,” said John Davisson, director of litigation at the Electronic Privacy Information Center. “That would mean Forewarn and likely many of its users are breaking the law.” The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has brought cases against companies for operating as consumer reporting agencies but failing to follow FCRA law, a spokesperson said, pointing to its $5.8 million September settlement with TruthFinder/Instant Checkmate. “Companies that compile personal information and sell background reports are on notice: Don’t make false claims about the contents of your reports,” Samuel Levine, Director of the Bureau of Consumer Protection at the agency said in a statement at the time. “If you market your reports to be used to screen tenants or employees, you are a consumer reporting agency and you must follow the requirements of the FCRA,” he added. A key FCRA protection gives consumers the right to know if the data used to profile them leads to their being excluded from housing opportunities so they can dispute its accuracy. Whether Forewarn’s data is always correct remains an open question for some of the real estate agent interviewed, who said they hope they are being fed accurate information. “You worry about the accuracy of any technology,” Anton said. “So far, we have no way of verifying.” “We certainly hope that [Forewarn] is pulling accurate records on individuals,” he added. Surging market penetration

A unique offering, but for what purpose?

One click bias?

What happens when the data is wrong?

Get more insights with the

Recorded Future

Intelligence Cloud.

No previous article

No new articles

Suzanne Smalley

is a reporter covering privacy, disinformation and cybersecurity policy for The Record. She was previously a cybersecurity reporter at CyberScoop and Reuters. Earlier in her career Suzanne covered the Boston Police Department for the Boston Globe and two presidential campaign cycles for Newsweek. She lives in Washington with her husband and three children.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh