I edit Wikipedia as a hobby, and recommend that hobby. (Fifteen or so years ago I was an early defender in the days when many scoffed at the Wikipedia idea.) I spent much of this past weekend on a long-running editing project, the entry for T.E. Lawrence, better known as Lawrence of Arabia. When I finished up on Monday I felt like a milestone had been passed so I decided to share, because the story behind it seemed worth telling.

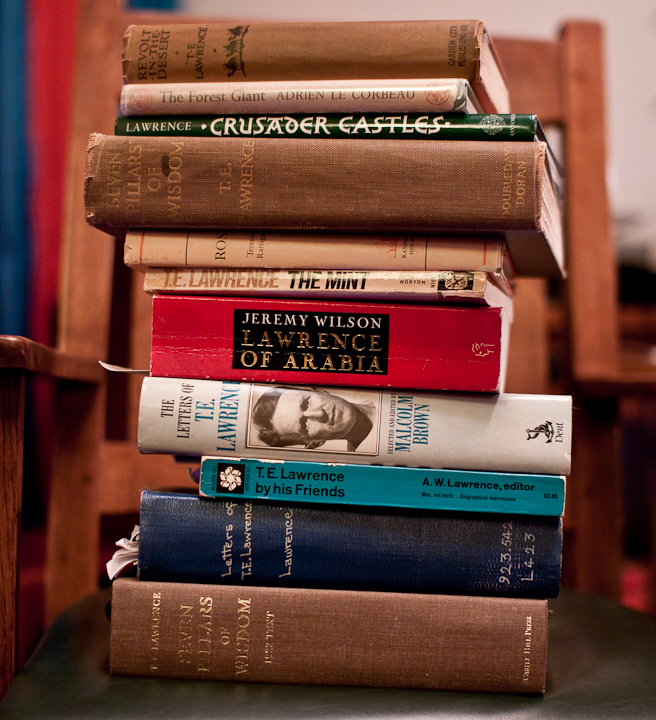

If you want the facts about Lawrence, go read the entry, it’s not that long. Briefly: An archeologist, he served in WWI as liaison between British forces in the Middle East and the “Arab revolt”, both of which were fighting the Ottoman Turks, allies of Germany. After the war, he became household-name famous, renounced that fame to serve as an enlisted man in the RAF, wrote a couple of books (Seven Pillars of Wisdom the best-known) and a huge volume of letters (fun to read) and died aged 46 in a motorcycle accident. His fame increased posthumously because of David Lean’s film Lawrence of Arabia, you’ve all seen it.

Editing this entry has consumed probably a few weeks of my life in aggregate, and I’m content with that. It involved one edit war with a crazed Islamist which required that I drive to the nearest university research library and consult obscure journals that nobody should ever have to look at. It has also turned me, I claim, into the world’s greatest living expert on Lawrence’s sexuality.

Meta-Lawrence · The entry has long had a reasonable description of the significant things Lawrence did. A related but distinct subject is the truth or falsity of his public image.

Immediately after the Great War ended, Lowell Thomas, an American impresario, toured with a multimedia presentation entitled With Allenby in Palestine and Lawrence in Arabia, including film, slides, dancing girls, and Thomas’ own narration. It was wildly successful and turned Lawrence into perhaps Britain’s most famous war hero of the time.

Two biographies were written during Lawrence’s lifetime, by B. H. Liddell Hart and Robert Graves. They were very rah-rah, attributing nearly godlike powers to their subject.

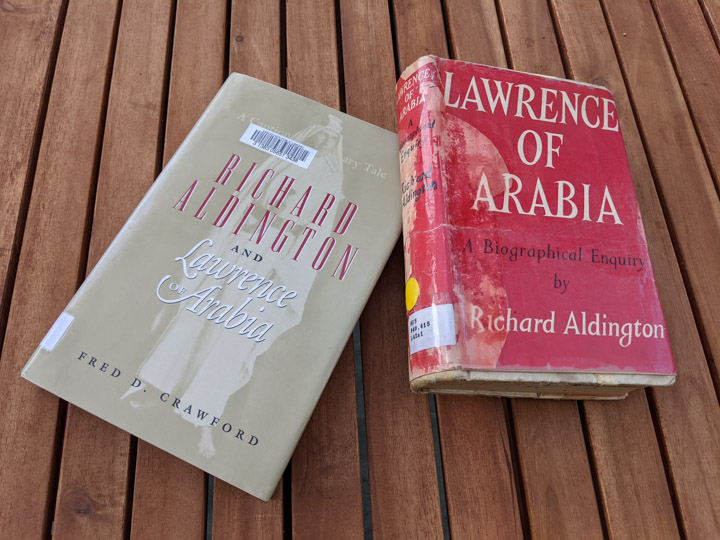

Then, in the early 1950s Richard Aldington, a well-regarded poet, novelist, and biographer, signed up to produce another tour of Lawrence’s life. His research convinced him that Lawrence was illegitimate, a liar, a sexual pervert, a self-promoter, and a bad writer, whose military contributions were negligible and misguided. Among other things, he discovered that Lawrence had significant input into the Graves and Liddell Hart biographies, apparently having written some sections himself.

Aldington’s draft biography, which said this at length, was leaked before publication. Lawrence’s surviving friends and admirers, horrified, sallied forth ready to rumble; the ensuing kerfuffle is quite a story. Liddell Hart led the “Lawrence Bureau” in an attempt to have the book suppressed. When that failed, he circulated hundreds of copies of an anti-Aldington tract to all the likely reviewers. This worked pretty well; when Lawrence of Arabia: A Biographical Enquiry was published in 1955, the reviews were savage; some showed evidence of having read Liddell Hart’s rebuttal but not Aldington’s book.

To be fair, the book was mean-spirited and full of anger, what today we’d call “trolling”. It also revealed that Aldington was a believer in the virtues of European colonial rule over brown people; exactly what Lawrence’s attempts to establish post-War Arab freedom were designed to thwart. Furthermore, Aldington (who lived in France) was also enraged by what he saw as Lawrence’s Francophobia — in fact, Lawrence’s efforts to block France’s colonial dreams were a function of his desire to see a free Arab state arise in Syria.

Prejudice aside, Aldington did discover and publish plenty of evidence of Lawrence having embellished the narrative of his life, and likely even invented some of it from whole cloth. He was particularly guilty of inflating numbers: Of bridges he’d blown up, of wounds he’d suffered, of the price on his head, and of the number of books he’d read. Subsequent biographers, most of whom remained admirers of Lawrence (as do I), freely acknowledge the truth of most of Aldington’s claims.

The whole thing is a hell of a story, best told by one Professor Fred D. Crawford in Richard Aldington and Lawrence of Arabia: A Cautionary Tale. It’s not exactly a bestseller; you’ll probably need to hit a big library to find a copy.

The production of Aldington’s book was a financial and emotional disaster for him from which he never fully recovered. Granted, he was clearly a “difficult person”, but still, one feels he deserved better.

Milestone? · Up until last week, the Wikipedia entry, while reasonably good on Lawrence’s military, political, and writing activities, had entirely ignored the Aldington controversy and ensuing revolution in Lawrence studies. No longer. Having whittled away at this thing for over a decade I think the entry is, broadly speaking, complete. Obviously no Wikipedia entry is ever finished because the course of human knowledge advances and better references can always turn up for the facts as outlined. But I still felt good when I posted the new section, and better still when, the next morning, it had picked up a couple of friendly edits and apparently failed to provoke any editorial opposition.

At this point I should emphasize that I don’t get to make the completeness call because I don’t “own” the Lawrence article; nobody owns anything in Wikipedia. Nor do I “lead” the editing in any meaningful sense. Many others have done lots of solid work over the years.

Join in! · This isn’t how I’d recommend everyone spend their weekends, but I find it rewarding sometimes. Who knows, you might too! Because everybody — everybody — is a world-class expert in something, be it only their own hometown, neighborhood, or hobby. Why not share that knowledge?

Wikipedia one of the few places on the Internet where truth is pursued, intently and unironically, for its own sake. It’s not perfect because nothing is, but everyone has the opportunity to make it more so.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh