These statistics are based on detection verdicts of Kaspersky products received from users who consented to providing statistical data.

The year in figures

In 2020, Kaspersky mobile products and technologies detected:

- 5,683,694 malicious installation packages,

- 156,710 new mobile banking Trojans,

- 20,708 new mobile ransomware Trojans.

Trends of the year

In their campaigns to infect mobile devices, cybercriminals always resort to social engineering tools, the most common of these passing a malicious application off as another, popular and desirable one. All they need to do is correctly identify the application, or at least, the type of applications, that are currently in demand. Therefore, attackers constantly monitor the situation in the world, collecting the most interesting topics for potential victims, and then use these for infection or cheating users out of their money. It just so happened that the year 2020 gave hackers a large number of powerful news topics, with the COVID-19 pandemic as the biggest of these.

Pandemic theme in mobile threats

The word “covid” in various combinations was typically used in the names of packages hiding spyware and banking Trojans, adware or Trojan droppers. Names we encountered included covid.apk, covidMapv8.1.7.apk, tousanticovid.apk, covidMappia_v1.0.3.apk and coviddetect.apk. These apps were placed on malicious websites, hyperlinks were distributed through spam, etc.

The mobile malware Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Agent.aq often hid behind another popular term, “corona”. Here are a few names of malicious files: ir.corona.viruss.apk, coronalocker.zip, com.coronavirus.inf.apk, coronaalert.apk, corona.apk, corona-virusapps.com.zip, com.coronavirus.map.1.1.apk, coronavirus.china.

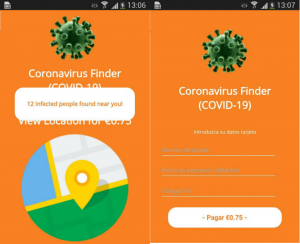

Of course, this was not limited to naming: the pandemic theme was also used in application user interfaces. For example, the GINP banking Trojan pretended to be an app that searched for COVID-19-infected individuals: the victim was coaxed into providing their bank card details under the pretext of a €0.75 fee charge.

The creators of another banking Trojan, Cebruser, simply named it “Coronavirus”, probably to echo the disturbing news coming from all over the world and to make some money along the way. As in the previous case, the attackers were after the bank card details and the owner’s personal information.

They came up with nothing new in terms of technique. So-called “web injectors”, which had been perfected for years, were used in both cases. When certain events are detected, the banking Trojan opens a window that displays a web page with a request for bank card details. The page can have any type of design: we have seen a request from a large bank in one case and a message about a search for COVID-19-infected individuals in another. The flexibility allows attackers to efficiently manipulate potential victims, adapting attacks to the situation both on a particular device and in the world at large.

We could conclude that the pandemic as a global phenomenon had a major effect on the mobile threat landscape, but to be true to facts, this is not entirely the case. If you look at the dynamics of attacks on mobile users in 2020, you will see that the average monthly number of attacks decreased by 865,000 compared to 2019. That number seems large, but it is only about 1.07% of total attacks, so we cannot call it a significant decrease.

Number of attacks on mobile users in 2019 and 2020 (download)

Besides, we have seen a decrease in attacks in the first half of 2020, which can be attributed to the confusion of the first months of the pandemic: hackers had other things to worry about. However, in the second half of the year, when the situation became calmer and more predictable despite lockdowns in a number of countries, we saw a clear increase in attacks.

In addition, our telemetry has shown significant growth in mobile financial threats in 2020. More on that later.

Adware

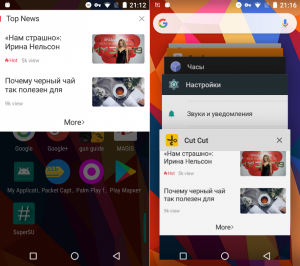

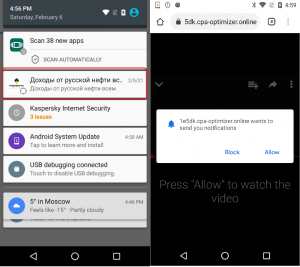

Last year was notable for both malware and adware, the two very close in terms of capabilities. Typically, code that runs ads was embedded in a carrier application, e.g. a mobile game or torch, as long as it was popular enough. After the application ran, it could follow one of several scenarios, depending on its creator’s greed and the advertising module’s capabilities. If the user was lucky, they saw an advertising banner at the bottom of the carrier application window, and if not, the advertising module subscribed to USER_PRESENT (device unlock) events, using a SYSTEM_ALERT_WINDOW window for displaying full-screen banners at random intervals.

Ad window (left) and carrier app definition (right)

In the latter case, the problem was not just the size of the banner, but also difficulty identifying the application that it was coming from. There were usually no technical obstacles to removing this application, and with it, the ads. We had recorded apps featuring aggressive advertising appearing in Google Play before, but 2020 proved rich in this kind of cases.

In terms of the number of attacks on mobile users, the situation around various advertising modules and applications looked more or less stable. This is probably one of the few classes of threats where the number of attacks hardly changed in 2020 as compared to the previous year.

Number of adware attacks on mobile users in 2019 and 2020 (download)

The number of unique users attacked by adware decreased slightly compared to 2019.

Users attacked by adware in 2018 through 2020 (download)

Interestingly enough, the share of adware attacks increased in relation to mobile malware in general. Whereas it was 12.85% in 2019, it reached 14.62% in 2020.

Distribution of attacks by type of software used in 2020 (download)

Adware creators are interested in obstructing the removal of their products from a mobile device. They typically work with malware developers to achieve this. An example of a partnership like that is the use of various trojan botnets: we saw a number of these cases in 2020.

The pattern is quite simple. The bot infects a mobile device and waits for a command, usually trying to avoid the victim’s attention. As soon as the owners of the botnet and their customers come to an agreement, the bot receives a command to download, install and run a payload, in this case, adware. If the victim is annoyed by the unsolicited advertising and removes the source, the bot will simply repeat the steps. In addition, trojans have been known to elevate access privileges on the device, placing adware in the system area and making the user unable to remove them without outside help.

Another example of the partnership is so-called preinstall. The manufacturer of the mobile device preloads an adware application or a component with the firmware. As a result, the device hits the shelves already infected. This is not a supply chain attack, but a premeditated step on the part of the manufacturer for which it receives extra profits. To add to that, no security solution is yet capable of reading an OS system partition to check if the device is infected. Even if detection is successful, the user is left alone with the threat, without a possibility of removing the malware quickly or easily, as Android system partitions are write protected. This vector of spreading persistent threats is likely to become increasingly popular in the absence of new effective exploits for popular Android versions.

Attacks on personal data

Almost any of the personal data stored on our smartphones can be monetized. In particular, advertisers can display targeted offerings, and attackers can access accounts with various services, such as online banking. It is thus small wonder that data is hunted: sometimes openly and sometimes illegally.

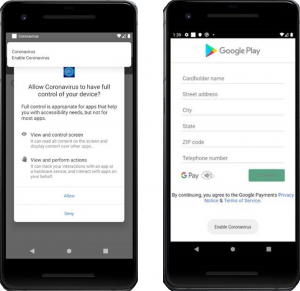

Ever since Android has introduced Accessibility Services, which provide applications with access to settings and other programs, the number of malware tools that extract confidential data from mobile devices has been on the rise. The Trojan Ghimob was one of 2020’s most exciting discoveries. It stole credentials for various financial systems including online banking applications and cryptocurrency wallets in Brazil. Ghimob used Accessibility for both extracting valuable data from application windows and interacting with the operating system. Whenever the user tried to access the Ghimob removal menu, the Trojan immediately opened the home screen to protect itself from being uninstalled.

Another exciting discovery was the Cookiethief Trojan. As the name implies, the malware targeted cookies, which store unique identifiers of web sessions and hence can be used for authorization. For example, an attacker could log in to a victim’s Facebook account and post a phishing link or spread spam. Typically, cookies on a mobile device are stored in a secure location and are inaccessible to applications, even malicious ones. To circumvent the restriction, Cookiethief tried to get root privileges on the device with the help of an exploit, before it began its malicious activities.

Apple iOS

According to various sources, the proportion of Android-powered devices in relation to all mobile devices ranges from 50% to 85% depending on the region. Apple’s iOS naturally comes second. So, what were the threats to that system in 2020? According to the Zerodium, exchange, the price of an iOS exploit chain is quite impressive, albeit lower than that for Android: $2,000,000 against $2,500,000. We are not aware of the Zerodium pricing mechanics, but the information suggests that attacks on Apple devices are a very popular commodity. Effective infection is only feasible though a drive-by download.

In 2020, our colleagues at TrendMicro detected the use of Apple WebKit exploits for remote code execution (RCE) in conjunction with Local Privilege Escalation exploits to deliver malware to an iOS device. The payload was the LightSpy Trojan whose objective was to extract personal information from a mobile device, including correspondence from instant messaging apps and browser data, take screenshots, and compile a list of nearby Wi-Fi networks. The Trojan was a modular design, with its individual components receiving updates. One of the modules discovered was a network scanner that collected information about nearby devices including their MAC addresses and manufacturer names. TrendMicro said LightSpy distribution took advantage of news portals, such as COVID-19 update sites.

Statistics

Number of installation packages

We discovered 5,683,694 mobile malicious installation packages in 2020, which was 2,100,000 more than in 2019.

Mobile malicious installation packages for Android in 2017 through 2020 (download)

The year 2020 can be said to have broken an established downward trend in the number of mobile threats discovered. There were not any special factors driving that, though.

Number of mobile users attacked

Mobile users attacked in 2019 and 2020 (download)

The number of users attacked steadily decreased over the past year. The number of users encountering mobile threats in 2020 was on the average a quarter lower than that in 2019.

Geography of mobile threats in 2020 (download)

Top 10 countries by share of users attacked by mobile malware

| Country* | %** |

| Iran | 67.78 |

| Algeria | 31.29 |

| Bangladesh | 26.18 |

| Morocco | 22.67 |

| Nigeria | 22.00 |

| Saudi Arabia | 21.75 |

| India | 20.69 |

| Malaysia | 19.68 |

| Kenya | 18.52 |

| Indonesia | 17.88 |

* Excluded from the rankings are countries with fewer than 25,000 active users of Kaspersky mobile security solutions in the reporting period.

** Users attacked in the country as a percentage of all users of Kaspersky Security for Mobile in the country.

Iran (67.78%) led by number of attacked users, mainly due to an aggressive spread of the AdWare.AndroidOS.Notifyer family. An alternative Telegram client, which we detect as RiskTool.AndroidOS.FakGram.d, acted as another widespread threat. This is not malware per se, but messages sent though the app can go to unintended recipients. A frequently detected malicious program was Trojan.AndroidOS.Hiddapp.bn whose objective was to download adware to an infected device.

Algeria ranked second with 31.29%. The AdWare.AndroidOS.FakeAdBlocker and AdWare.AndroidOS.HiddenAd families were the most widespread ones in that country. Two of the most widespread malicious programs were Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Agent.ok and Trojan.AndroidOS.Agent.sr.

Rounding out the “top three” was Bangladesh with 26.18%, where the FakeAdBlocker and HiddenAd adware families were also the most widespread ones.

Types of mobile threats

Distribution of new mobile threats by type in 2019 and 2020 (download)

Twelve of twenty-two types of mobile threats showed an increase in the number of detected installation packages in 2020, with the most significant growth demonstrated by adware: from 21.81% to 57.26%. In absolute terms, the number of packages more than quadrupled: 3,254,387 in 2020 against 764,265 в 2019. Unsurprisingly, the share of the former leader, RiskTool, dropped from 32.46% to 21.34%. Third place, as in 2019, was occupied by malware, such as Trojan-Dropper (4.51%) whose share also decreased markedly, by 11.58 p.p.

Adware

The vast majority (almost 65%) of adware discovered in 2020 belonged to the Ewind family. The most common member of that family was AdWare.AndroidOS.Ewind.kp, with more than 2,100,000 installation packages.

Top 10 adware families discovered in 2020

| Name of family | %* |

| Ewind | 64.93 |

| FakeAdBlocker | 15.27 |

| HiddenAd | 10.09 |

| Inoco | 2.16 |

| Agent | 1.12 |

| Dnotua | 0.84 |

| MobiDash | 0.69 |

| SplashAd | 0.66 |

| Vuad | 0.64 |

| Dowgin | 0.47 |

* Share of the adware family in the total number of adware packages

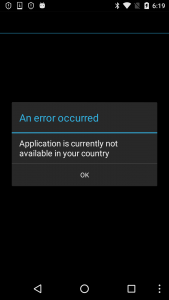

The Ewind family is an example of aggressive adware. Its members try to monitor the user’s activities and counteract attempts at removal. In particular, the aforementioned Ewind.kp variant displays an error message upon starting.

AdWare.AndroidOS.Ewind.kp screenshot

As soon as the user taps OK, the app window will close and its icon will be hidden from the home screen. After that, the Ewind.kp will monitor the user’s activity and display advertising windows at certain points. In addition to banners in the notification bar, the app will open promoted sites, such as online casinos, in a separate browser window.

Advertising banner (left) and open Ewind.kp browser window with a promoted website (right)

Where did the more than two million Ewind.kp packages come from? Its creators exploit the content of legitimate applications, such as icons and resource files. Resulting packages seldom do anything useful, but Ewind applications created with others’ content could fill up a fake app marketplace. They all have diverse names, icons and installation package sizes, so an unsophisticated user might not even suspect anything is amiss about the store.

The best part of it is that the AdWare.AndroidOS.Ewind.kp variant has been known since 2018, and we have never once had to adjust the process of detecting it in almost three years. Individuals who generate that many installation packages are obviously not worried about antivirus software.

RiskTool

RiskTool-class applications remained one of the three most relevant threats even without showing a significant growth in 2020. Their share declined in relation to others, but in absolute terms, the threats in that class even gained relevance. The major contributing factor was the SMSReg family, which doubled in number to 424,776 applications compared to 2019.

Top 10 RiskTool families discovered in 2020

| Name of family | %* |

| SMSreg | 41.75 |

| Robtes | 16.13 |

| Agent | 9.67 |

| Dnotua | 7.72 |

| Resharer | 7.50 |

| Skymobi | 5.29 |

| Wapron | 3.42 |

| SmsPay | 2.78 |

| PornVideo | 1.41 |

| Paccy | 0.76 |

* Share of the RiskTool family in the total number of RiskTool packages

Other threats

The number of backdoors detected almost tripled from 28,889 in 2019 to 84,495 in 2020. However, most of the detected threats notably belonged to older families whose relevance was questionable. Where did these come from? Many members of these families became publicly available, serving as test subjects: for instance, their code was obfuscated to test the antivirus engine’s detection quality. This does not make a whole lot of sense, as obfuscation is only effective against engines with very limited capabilities. More importantly, however, the legality of these activities is doubtful: lab tests on malware code are acceptable, but publication of samples is ethically questionable at the very least.

The number of detected Android exploits increased seventeenfold. LPE exploits, relevant to Android versions 4 through 7, accounted for most of the growth. As for exploits for more recent versions of that OS, they are typically device specific.

The number of Trojan-Proxy threats has increased by twelve times. This type of malware is used by hackers for establishing secure tunnels which they can then use as they see fit. A major threat to the victims is the use of their mobile devices as a mediator in criminal offenses, e.g. downloading of child pornography. This may result in law enforcement agencies taking an interest in the owner of the infected device and asking them questions they would rather avoid. For companies, a secure tunnel between an infected corporate smartphone and an unknown attacker means unauthorized third-party access to internal infrastructure, which, to put it mildly, is undesirable.

Top 20 mobile malware programs

The following malware rankings omit riskware, such as RiskTool and AdWare.

| Verdict | %* | |

| 1 | DangerousObject.Multi.Generic | 36.95 |

| 2 | Trojan.AndroidOS.Boogr.gsh | 9.54 |

| 3 | DangerousObject.AndroidOS.GenericML | 6.63 |

| 4 | Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Necro.d | 4.08 |

| 5 | Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Hqwar.cf | 4.02 |

| 6 | Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.Agent.ado | 4.02 |

| 7 | Trojan.AndroidOS.Hiddad.fi | 2.64 |

| 8 | Trojan.AndroidOS.Agent.vz | 2.60 |

| 9 | Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Helper.a | 2.51 |

| 10 | Trojan.AndroidOS.Handda.san | 1.96 |

| 11 | Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Agent.ic | 1.80 |

| 12 | Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Agent.hy | 1.67 |

| 13 | Trojan.AndroidOS.MobOk.v | 1.60 |

| 14 | Trojan.AndroidOS.LockScreen.ar | 1.49 |

| 15 | Trojan.AndroidOS.Piom.agcb | 1.49 |

| 16 | Trojan.AndroidOS.Hiddapp.ch | 1.46 |

| 17 | Exploit.AndroidOS.Lotoor.be | 1.39 |

| 18 | Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Hqwar.gen | 1.34 |

| 19 | Trojan.AndroidOS.Necro.a | 1.29 |

| 20 | Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Agent.rb | 1.26 |

* Share of users attacked by this type of malware in total attacked users

The leaders among the twenty most widespread malicious mobile applications were unchanged from 2019, with only their shares changing slightly. The leader was DangerousObject.Multi.Generic (36.95%), the verdict we use for malware detected by using cloud technology. The verdict is applied where the antivirus databases still lack the signatures or heuristics for detection. The most recent malware is detected that way.

The Trojan.AndroidOS.Boogr.gsh verdict ranked second with 9.54%. It is assigned to files recognized as malicious by our ML-powered system. Another result of this system’s work is objects with the verdict DangerousObject.AndroidOS.GenericML (6.63%, ranking third). The verdict is assigned to files whose structure bears a strong similarity to previously known ones.

Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Necro.d (4.08%) ranked fourth. Unlike other malicious programs in that family, which are installation packages, the Necro.d variant is a native ELF executable. We typically detected that Trojan in the read-only system area. It could only make its way there via another Trojan that exploited system privileges or as part of the firmware. Necro.d apparently used the latter path, as one of its capabilities is uploading KINGROOT, a package used for elevation of privileges. Necro.d’s mission is to download, install and run other apps when instructed by attackers. In addition, it provides remote access to the shell of the infected device.

The Hqwar dropper ranked fifth and eighteenth simultaneously. This malicious “phoenix” seems to be rising from the ashes, with 39,000 users showing that they were infected in 2020 compared to 28,000 in 2019. Hqwar in a nutshell:

- This is a nesting-doll malicious program that has an external dropper shell next to an obfuscated DEX executable payload.

- Its main objective is evading detection by the antivirus engine if the device has a security solution installed.

- Banking Trojans typically serve as the payload.

Number of users attacked by Hqwar droppers in 2019 and 2020 (download)

In most cases, banking Trojans unloaded by Hqwar were focused on targets in Russia, specifically, applications operated by Russian financial institutions.

Top 10 countries by number of users attacked by Hqwar

| Country | Share of attacked users | |

| 1 | Russia | 305861 |

| 2 | Turkey | 22138 |

| 3 | Spain | 15160 |

| 4 | Italy | 8314 |

| 5 | Germany | 3659 |

| 6 | Poland | 3072 |

| 7 | Egypt | 2938 |

| 8 | Australia | 2465 |

| 9 | Great Britain | 1446 |

| 10 | USA | 1351 |

Trojan-SMS.AndroidOS.ado(4.02%) ranked sixth in the TOP 20 list of mobile malicious programs. This is a typical example of the kind of old-school text-message scams that were popular in 2011 and 2012. Their enduring relevance is a surprise. The Trojan targets Russian-speaking audiences, as Russia is a country with a mature market for buying content by sending text messages to paid phone numbers. This is a modern design, though: the Trojan uses an obfuscator as protection against reverse engineering and detection, and receives commands from external operators. Agent.ado is distributed under the guise of an app installer.

Trojan.AndroidOS.Hiddad.fi (2.64%) ranked seventh. This Trojan handles installation of adware in an infected system, but it can display ads as well.

Trojan.AndroidOS.Vz (2.60%) ranked eighth, a malicious module loaded by other Trojans including members of the Necro family. It serves as an intermediate link in the infection chain, and it is responsible for downloading further modules, for instance, Ewind adware, mentioned above.

Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Helper.a (2.51%) ranked ninth. It exemplifies occasional difficulty removing mobile malware from the system. Helper is part of a chain that includes Trojans elevating their access rights on the device and writing themselves or Helper to the system area. In addition to that, the Trojans make changes to the factory reset process, leaving the user few chances to get rid of the malware without outside help. The approach is nothing new, but we saw plenty of users complaining on the Internet about the difficulty they were having removing Helper, something we had not seen before.

Trojan.AndroidOS.Handda.san (1.96%) rounds out the first ten This verdict is an umbrella for a whole group of malicious programs, which include trojans with shared capabilities: icon hiding, obtaining Device Admin rights and using packers to counteract detection.

Trojans in the Trojan-Downloader.AndroidOS.Agent family ranked eleventh and twelfth, their only objective being downloading a payload when instructed by the operators. In both cases, the payload is encrypted and traffic cannot be interpreted to indicate what exactly is being loaded onto the device.

Trojan.AndroidOS.MobOk.v (1,60%) ranked thirteenth. MobOk trojans can automatically subscribe a victim to paid services. They attempted to attack users in Russia more frequently than others in 2020.

The primitive Trojan.AndroidOS.LockScreen.ar Trojan (1,49%) ranked fourteenth. This malware was first spotted in 2017. Locking the device screen is its only mission.

Trojan.AndroidOS.Hiddapp.ch (1,46%) ranked sixteenth. We assign this verdict to any app that hides its icon in the list of apps immediately upon starting. Subsequent steps may vary, but these are typically downloading or dropping other apps, or displaying ads.

Exploit.AndroidOS.Lotoor.be (1,39%), a local exploit for elevating privileges to the superuser, ranked seventeenth. Its popularity should not be surprising, as this type of malware is capable of downloading Necro, Helper and other Trojans in our Top 20.

Trojan.AndroidOS.Necro.a (1,29%), which ranked nineteenth, is a chain of Trojans. It takes root in the system, and it sometimes proves difficult to remove, along with associated Trojans.

Rounding out our Top 20 is Trojan-Dropper.AndroidOS.Agent.rb (1,26%). It serves various groups, and objects it is used to pack include both malware and perfectly legitimate software. There are notably two variants: in the first case, the code for decrypting the payload is located in a native library loaded from the main DEX file, and in the second, the dropper code is concentrated within the body of the main DEX file.

Mobile banking trojans

We detected 156,710 installation packages for mobile banking Trojans in 2020, which is twice the previous year’s figure and comparable to 2018.

Mobile banking Trojan installation packages detected by Kaspersky in 2017 through 2020 (download)

Whereas the statistics for 2018 were seriously affected by an epidemic of the Asacub trojan, the major culprits last year were objects from the Trojan.AndroidOS.Agent family. That family’s share was just 19.06% in 2019, jumping to 72.79% in 2020.

Top 10 banking trojans discovered in 2020

| Name of family | %* |

| Agent | 72.79 |

| Wroba | 5.44 |

| Rotexy | 5.18 |

| Anubis | 2.88 |

| Faketoken | 2.48 |

| Zitmo | 2.16 |

| Knobot | 1.53 |

| Gustuff | 1.48 |

| Cebruser | 1.43 |

| Asacub | 1.07 |

* Share of the mobile banker trojan family in the total number of mobile banker trojan packages

Agent.eq was the most prolific of all Agent (72.79%) variants. The heuristics turned out to be universal, helping us detect malware belonging to Asacub, Wroba and other families.

The Korean malware Wroba, spread by its operators through smishing, in particular, by sending fake text messages from a logistics company, ranked second. Like many others of its kind, the malware shows the victim one of a number of preset phishing windows, depending on what financial app is running on the home screen.

The rest of the programs included in the rankings have been well known to researchers for a long time. One exception might be Knobot (1.53%), a relatively new player that targets financial data. Along with phishing windows and interception of 2FA verification messages, the Trojan is equipped with several tools that are uncharacteristic of financial threats. An example of these is hijacking device PINs through exploitation of Accessibility Services. The hackers might need the PIN for manually controlling the device in real time.

Attacks by mobile banking trojans in 2019 and 2020 (download)

The surge in attacks in August 2020 is attributed to the Asacub, Agent and Rotexy families. It is through their escalating spread that the stable picture observed up until July was changed.

Top 10 families of mobile bankers

| Family | %* |

| Asacub | 25.63 |

| Agent | 17.97 |

| Rotexy | 17.92 |

| Svpeng | 12.81 |

| Anubis | 12.36 |

| Faketoken | 10.97 |

| Hqwar | 5.59 |

| Cebruser | 2.52 |

| Gugi | 1.45 |

| Knobot | 1.08 |

* Share of users attacked by the family of mobile bankers in total users attacked by mobile banking Trojans

Geography of mobile bankers attacks in 2020 (download)

Top 10 countries by share of users attacked by mobile bankers

| Country* | %** | |

| 1 | Japan | 2.83 |

| 2 | Taiwan Province, China | 0.87 |

| 3 | Spain | 0.77 |

| 4 | Italy | 0.71 |

| 5 | Turkey | 0.60 |

| 6 | South Korea | 0.34 |

| 7 | Russia | 0.25 |

| 8 | Tajikistan | 0.21 |

| 9 | Poland | 0.17 |

| 10 | Australia | 0.15 |

* Excluded from the rankings are countries with fewer than 25,000 active users of Kaspersky mobile solutions in the reporting period.

** Unique users attacked by mobile bankers in the country as a percentage of all users of Kaspersky mobile solutions in the country.

Compared to 2019, the distribution of countries by number of users attacked by mobile bankers changed significantly. Russia (0.25%), which had ranked first for three years, dropped to seventh place. Japan (2.83%), where the aforementioned Wroba raged, ranked first. The situation was similar in Taiwan (0.87%), which ranked second in our Top 10. Third was Spain (0.77%), where the most popular bankers were Cebruser and Ginp.

Italy (0.71%) ranked fourth. The most common threats in that country were Cebruser and Knobot. In Turkey (0.60%), ranked fifth, users of Kaspersky security solutions most often encountered the Cebruser and Anubis families.

The most widespread banking trojan in Russia (0.25%) was Trojan-Banker.AndroidOS.Rotexy.e, followed by Svpeng.q and Asacub.snt.

Mobile ransomware Trojans

We found 20,708 installation packages for ransomware Trojans in 2020, a decrease of 3.5 times on the previous year.

Ransomware Trojan installation packages in 2018 through 2020 (download)

Overall, the decrease in ransomware can be associated with the assumption that attackers have been converting from ransomware to bankers or combining the features of the two. Current versions of Android prevent applications from locking the screen, so even successful ransomware infection is useless.

However, in the field of mobile ransomware, we were in for a nasty surprise.

Users attacked by mobile ransomware Trojans in 2019 and 2020 (download)

Whereas the beginning of 2020 saw a decrease in the number of users attacked by ransomware trojans, we observed a spike in September, with the indicator then returning to July’s figures.

Looking closer, we found out that Trojan-Ransom.Win32.Encoder.jya was the most widespread type of ransomware in September. As the verdict shows, the malware is not designed for the Android platform — it is an encryptor that targets files on Windows workstations. How did that end up on mobile devices? The explanation is simple: September saw Encoder.jya spread via Telegram, while the instant messaging app has both a mobile and desktop client. The attackers clearly targeted Windows users, while mobile users received the malware, one might say, accidentally, due to the mobile version of Telegram syncing downloads with the desktop client. Once in the smartphone memory, the malware was successfully detected by Kaspersky security solutions. A file containing Encoder.jya was most often named as 2-5368451284523288935.rar or AIDS NT.rar.

Geography of mobile ransomware attacks in 2020 (download)

Top 10 countries by share of users attacked by ransomware Trojans

| Country* | %** |

| USA | 2.25 |

| Kazakhstan | 0.77 |

| Iran | 0.35 |

| China | 0.21 |

| Italy | 0.14 |

| Canada | 0.11 |

| Mexico | 0.09 |

| Saudi Arabia | 0.08 |

| Australia | 0.08 |

| Great Britain | 0.07 |

* Excluded from the rankings are countries with fewer than 25,000 active users of Kaspersky mobile solutions in the reporting period.

** Unique users attacked by mobile ransomware in the country as a percentage of all users of Kaspersky mobile solutions in the country.

As in 2019, the United States was the country with the most attacked users (2.25%) in 2020. The most common family of mobile ransomware in the country was Svpeng. Kazakhstan (0.77%) ranked second again, Rkor being the most widespread ransomware in that country. Iran (0.35%) remained in third position in our Top 10. The most common type of mobile ransomware there was Trojan-Ransom.AndroidOS.Small.n.

Conclusion

The 2020 pandemic has affected every aspect of our lives, and the landscape of mobile threats has been no exception. We saw a decrease in the number of attacks in the first half of the year, which can be attributed to the confusion of the first months of the pandemic: the attackers had other things to worry about. They were back at it in the second half, though, and we saw an increase in attacks involving mobile bankers, such as Asacub and Wroba. Besides that, we saw stronger interest in banking data, both from criminal groups specializing in mass infections and from those who prefer to select their targets carefully. And this, too, was affected by the pandemic: the inability to visit a bank branch forced customers to switch to mobile and online banking, and banks, to consider stepping up the development of those services.

Another statistically interesting event was an increase in adware, with the Ewind family making a major contribution to this: we discovered more than 2,000,000 packages of the Ewind.kp variant alone. However, these volumes had little, if any, impact on attack statistics. Coupled with Ewind.kp developers’ reluctance to make changes to the core application code, this may indicate that they have opted for quantity over quality.

如有侵权请联系:admin#unsafe.sh